********

March 24, 2012

Elle s’appelait Simone Signoret. France. 2010. French with English subtitles.

The American public will remember Simone Signoret as the first French actress to win a Hollywood Oscar.

French filmgoers will, more often than not, think of her as the female villain of the piece. Tabloid readers will marvel at her famous pronouncement when her husband, Yves Montand, became involved with Marilyn Monroe. Here I paraphrase: “It will be impossible for Yves to unravel all the threads that tie us together”. Their marriage lasted until her death. As far as today’s generation of botoxed and carved-up starlets is concerned, there might be grudging admiration for a woman who dared, not only to act her age, but even older. Signoret was not afraid of displaying her battle-scars on screen, although off- screen she admitted that she could have taken better care of her physical appearance.

To militants all over the world she will always be worthy of admiration and hopefully, emulation, because she acted on her convictions with courage and determination regardless of the cost. She and Yves were often seen together defending victims of blatant injustices. However, like many progressives of her generation, she felt betrayed when the depths of Stalin’s perfidy became known.

I will always think of her as the daughter of Andre Kaminker, a pioneer interpreter who worked during the Nuremberg trials and founded AIIC, the Geneva-based International Association of Conference Interpreters.

Do see this film. They don’t make them like that any more… actresses, that is.

[Maya Khankhoje, who was a member of AIIC for over three decades, still remembers her childhood horror when she watched Simone Signoret in Les Diaboliques.]

********

March 22, 2012

The Toledo Report, Mexico, 2009. Spanish/Zapotec/English with English subtitles.

Francisco Toledo is a graphic artist, painter and story teller from Juchitan, Oaxaca. The Zapotec speaking municipality of Juchitan not only defeated the French troops that invaded Mexico in 1866 but also installed a left-wing pro-socialist government in the late 20th Century. Toledo comes from such hardy stock.

Francisco Toledo’s work has been greatly influenced by Dürer, his readings of European literature and his student days in Paris. There he shared a studio with other artists from whom he learned a lot and to whom he taught a lot, not to forget, of course, Mexican folk art and mysticism. This film documents Toledo’s life, his artistic trajectory as well as his fiery political involvement. The documentary contains old footage, new interviews and animation based on Toledo’s engravings which in turn are based on Kafka’s Peter the Red. There Toledo describes himself as an ape who learns from others, a clin d’oeil to his Parisian experience.

However, not everything is black and white in Toledo’s work or his thinking, as evidenced in his paintings and sculptures informed by Mexico’s oral history. The crocodile and other reptiles are a recurring theme in Toledo’s work, as well as other animals that inhabit the Mexican jungles. The ape, of course, is used by the artist in many of his self-portraits.

Like Gaudí, Toledo participated in several architectural projects with massive sculptures, notably in the very modern and industrialised city of Monterrey.

To watch this film is to both get a privileged glimpse into life in El México Profundo and a coherent answer to a nagging question: What is the link between art and revolution?

[When Maya Khankhoje and her daughter Shanti were holidaying in Huatulco they were unable to visit neighbouring Juchitan because of the standoff between the federal government and the people’s government of Juchitan.]

********

March 20, 2012

La Famille Stein, la fabrique d’art moderne. France, 2011, French/English.

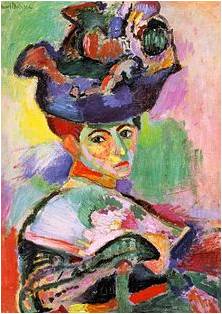

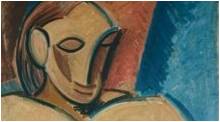

Cézanne, Gauguin, Matisse, Picasso and Juan Gris have one thing in common, aside from being modernist painters. They all visited Gertrude Stein´s salon in Paris at some point or another , or at least had their works hung on those high walls of her apartment. Initially it was her brother Leo´s apartment, later she joined him and lived with him until he left and she set up house with her companion Alice B. Toklas. They say it was Leo who knew about paintings and that Gertrude learned from him. Others say it was the alchemy between these two siblings as well as the zeitgeist of Europe that produced such fine collections which later made their way to museums all over the world. Be it as it may, all art lovers have gained from this marriage-like relationship between these two siblings, both of them outside the norms of accepted heterosexuality for the period. Unlike a marital couple, however, they had no problems splitting the collection when they went their separate ways.

It is one thing to acquire an art collection if you receive money from your hard working older brother in San Francisco and buy paintings from hitherto unknown painters at a favorable rate of exchange in Paris. It is another to know that what you are buying, bold and innovative for those times, will be recognized –and endure- as masterpieces down the years and into the following century.

Leo and Gertrude had a special gift. Watch the movie and you will be regaled with authentic footage of Gertrude reciting some of her literary pieces and you might even get a glimpse of Picasso when he had a full head of hair.

[Maya Khankhoje has never understood why Gertrude Stein is considered such a literary figure. After watching the film she is eager to read more of her work.]

********

March 19, 2012

Georgia O’Keeffe, Emily Carr and Frida Kahlo were three of the most important painters, men or women, of the 20th Century.

Both O’Keeffe and Carr drew their inspiration from nature, the former from the deserts of New Mexico and the latter from the lush forests of Western Canada.

Kahlo, on the other hand, drew her inspiration from her personal pain and the bright colours of the Mexican landscape.

Each painter had a unique style, but the three of them walked a path strewn with obstacles. Whereas Emily and Georgia lived and painted in solitude, Kahlo thrived in human company.

The narrative is taken from the diaries and correspondence of the three women thus providing viewers with a glimpse into their hearts, minds and eyes.

The film could have shown more images of the incredible art of these painters. However, in the case of Kahlo, the film gained by showcasing some lesser known works.

[When Maya Khankhoje was a little girl she often accompanied her father on visits to her old friends Diego and Frida. She’ll never forget the image of Frida lying on her bed with her easel hanging from the ceiling.]

**

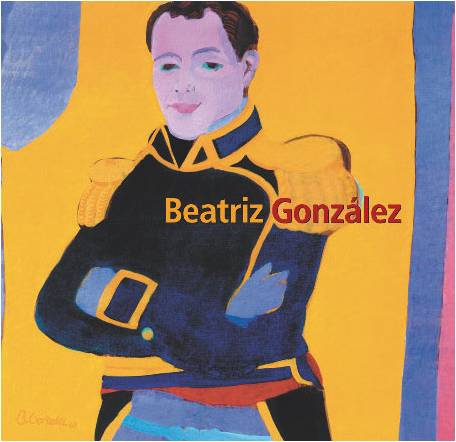

Beatriz González, ¿Por Qué Llora Si Ya Reí?

Beatriz González, born in 1938, is one of Colombia´s foremost painters. She has been called the Latin American response to pop culture because some of her work is reminiscent of Andy Warhol’s silk screens. But the resemblance stops there.

As a child she was nicknamed “the artist”. Her rambunctious siblings did not enjoy the privilege she enjoyed: that of accompanying her father on different outings and errands during which he would comment on everything they saw. Beatriz learned to be observant, to question what she saw and to rebel against the “good taste” which her genteel mother had tried to instil in her.

This rebellious spirit led her to mock politicians whom she judged to be leading the country towards fascism as well as to explore the meaning of taste, good or bad. For her a pluralistic society is a healthy one.

Beatriz started out by deconstructing copies of famous paintings or newspaper photographs to create something entirely new. With a 50-year history of armed conflict in Colombia, she realized that humour was no longer a valid weapon. The newspapers chronicled so many tragedies, both personal and political, that her art began to be steeped in tears rather than laughter. However, it is not lugubrious. The combination of pathos and the luminous colours of Colombian popular art is visually stunning and healing.

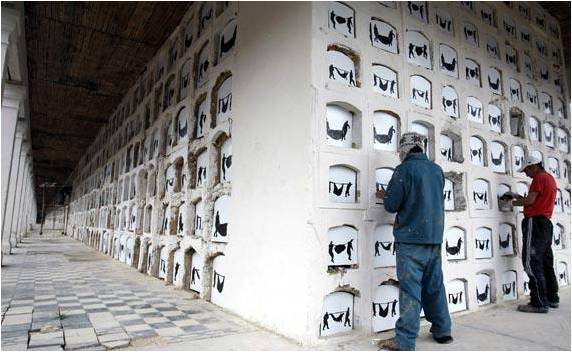

When demolitions started in the 1836 Central Cemetery of Bogota to make room for a park and other amenities, people were shocked. Colombian traditions, although formally Catholic, are also deeply rooted in voodoo. They felt that the souls of the dead would wander eternally over the city. Beatriz González, of a more rational and humanistic bent, lamented the loss of historical memory and a place to grieve. When she realized that there were several units housing 8957 empty niches which had not yet been demolished she set out to rescue them by designing tombstones. For this, she created several silk-screen patterns to cover each and every empty columbarium so that “the wandering souls could be contained”. With this she also hoped to give meaning to a future Memory, Peace and Reconciliation Centre honouring the victims of violent death. Her designs depict dead bodies being carried the traditional way: tied with a rope, lying on a hammock or simply wrapped in a plastic sheet.

Beatriz González is aware that her art is ephemeral. She hopes other artists follow her lead.

[Maya Khankhoje was close to tears after viewing this film, but her spirits were uplifted when she bumped into Rax Rinnekangas who recommended she view his film: A Journey to Eden, very fittingly, about and forgiveness. More anon.]

********

March 18, 2012

Intime Etranger, France/Japan, 2011.

This meditative film follows the production of two abstract paintings by Japanese artist Hitoshi Mori, whose body harbours a slow form of cancer. The painter seeks out a barren rock-strewn landscape and paints a couple of huge rocks, or rather, the space between them. In between bouts of painting he either rests or visits the doctor in the company of his wife. He also occasionally shares a beer and a chat with friends, or gardens in his kitchen plot. Everything is grey, the rocks are several shades of grey and so are the paintings which become more and more abstract as they reach completion. Bursts of green Japanese landscapes punctuate the narrative. There are neither highlights nor dramatic moments in the movie. It is all very Zen and very soothing. Just close your eyes and image the paintings for which, unfortunately, the festival failed to provide visuals.

Is the intimate stranger the illness that is eating the painter away? Or is it the slow process of creating an abstract masterpiece, a la Japanese with a touch of Parisian chic?

[Maya Khankhoje was fascinated by the process of creating an abstract painting which appears to involve a lot of meditation and a touch of slapdash.]

********

March 17, 2012

Les Ambassadeurs d’Holbein—Rendez-vous avec la mort. France, 2010.

The Ambassadors (1533) is perhaps one of Hans Holbein the Younger’s most important works. It forms part of the curriculum of most art history and art appreciation courses. It depicts two men symbolizing secular and religious power as well as three levels of human life: the heavens, life on earth and death. Such a type of painting containing still lives and a double portrait is often known as a Vanitas. On the upper left-hand corner there is a crucifix partially hidden by the curtain and at the bottom centre part there is a skewed skull depicted in anamorphic perspective. If the viewer views it from the right hand corner its perspective will be compressed appearing as a normally shaped skull.

The objects in the centre are scientific instruments depicting latitudes, longitudes and other types of measurements whereas the broken string on the musical instrument denotes disharmony, perhaps of a geopolitical nature or between secular and religious powers. The rug is oriental and the mosaic on the floor is a copy of the design on Westminster Abbey. This latter detail is explained by the fact that although Holbein was Germanic by birth he spent many years in England painting the portraits of King Henry VIII and a couple of his wives.

The movie is technically impeccable, thought-provoking and engaging. Its most interesting feature is the panorama of the times offered by the narrator.

********

March 16, 2012

Casa Estudio por Luis Barragán. Finland 2010.

Where can you watch a film about an eminent Mexican architect narrated in Finnish with English subtitles? In French-speaking Montreal, of course, thanks to FIFA.

Casa Estudio, as the name implies, was the home and study of Luis Barragán, an engineer and self-taught architect who went on to win the Pritzker Prize, the equivalent of the Nobel Prize in architecture.

He was greatly influenced by Le Corbusier, the Bauhaus movement and Islamic architecture and has often been described as a minimalist. However, even though he can certainly be called a modernist, his use of colour and natural materials such as wood and stone, have set his work apart. For him, design should reflect emotional contact. As far as Barragán was concerned, a house should not stand out from its surroundings which is why Casa Estudio is unprepossessing on the outside. He also believed that a home should reflect serenity and silence. Therefore it has a Zen-like quality on the inside and is alive with colour and light.

Even though Barragán designed the urban plan for El Pedregal, a luxurious neighbourhood in Mexico where the houses are landscaped on lava rock, he chose to build his home in a working-class neighbourhood. It was built in 1947 and UNESCO added it to its list of World Heritage in 2004.

[Maya Khankhoje, who was born in Mexico City, used to think Mexican architecture was outstanding. She no longer thinks that, now she knows for sure.]

**

Ai Weiwei. Without Fear or Favour. United Kingdom, 2010, Mandarin/English.

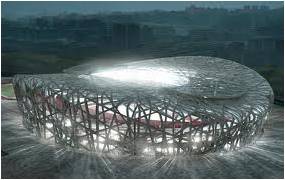

Ai Wei Wei is a Chinese artist and activist engaged in curating, sculpture, ceramics, installations, architecture, photography and film. He is also a social, political and cultural critic. A true renaissance man of the 21st Century who, according to this BBC film, is answerable only to himself, that is, to his artistic truth. His politics are equally scathing against Mao’s vision of China and its current capitalistic orgy. He helped design the Beijing National Stadium, otherwise known as the Bird’s Nest for the 2008 Olympics yet he distanced himself from the Olympics themselves, decrying what they stood for. Why then did he agree to design the stadium? Because he thought his design was beautiful.

Whatever he is, he is true to himself, a man “without fear or favour”, who rose from poverty to great wealth and back again to penury, funnelling all his earnings back into his art.

These contradictory characteristics are not surprising, considering his father was Ai Qing, a beloved national poet and ardent communist who was exiled by the government in 1957 for defending Ding Ling, a Chinese woman author accused of rightism.

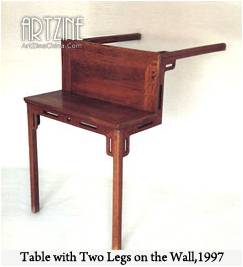

This thought-provoking film traces Ai Weiwei’s evolution as an artist, his self-exile to New York where he was influenced by members of the beat generation like Ginsberg and where, out of poverty and necessity, he learned how to create art –conceptual art- with whatever materials were available to him. He also learned to destroy Ming vases and tamper with antique furniture to make a point about their value.

It also shows his return to China following his father’s illness triggered by the Tiananmen Square events and his decision to actively participate in his country’s destiny.

The most important piece of art showcased in this film was commissioned for an unknown amount by the Tate Gallery in London. It was two and a half years in the making and consists of 100 million, yes, 100,000,000 porcelain sunflower seeds made by hand by hundreds upon hundreds of artisans in the region where Ming vases were originally made. But this is a gross exaggeration, the Tate Gallery only bought 8 million seeds for display.

Ai Weiwei uses art to turn on itself. How subversive is that?

[When Maya Khankhoje visited Beijing the city was still ruled by bicycles, but that was in the last century.]

********

March 15, 2012

The 30th Edition of the International Festival of Films on Art kicked off on 15th March and will continue till the 25th of the month. It showcases 232 documentaries –and a few feature films – from 27 countries on art, architecture, literature, dance, fashion, music and painting.

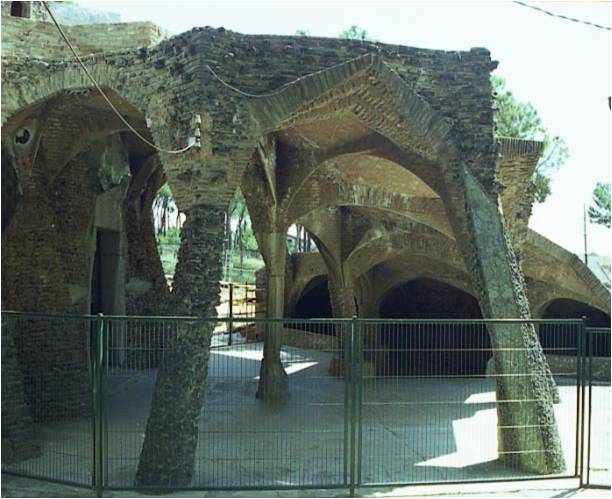

Montreal Serai’s pick for today is Gaudí, le dernier bâtisseur [France, 2010, color, French/Spanish] previewed in the Festival’s excellent media facilities. Catalan architect Antoni Gaudí (1852-1926), master builder of the Expiatory Temple of the Holy Family (Sagrada Familia) in Barcelona came from a long line of artisans who knew how to build structures and fashion objects out of wood, clay, construction materials, metal, glass and other materials taken from nature. Those skills, together with his formal architectural studies, made him a remarkable builder, architect, sculptor and artist in general. He was also a deeply religious person who shared medieval man’s veneration for places of worship which were anchored in the earth but reached out to high heavens. As far as he was concerned, cathedrals had to look like forests and they did. His main inspiration was the rugged topography of Catalonia, his natal province, as well as its idiosyncratic vegetation. His great love of nature is reflected in his penchant for curves and asymmetry. How can his curvilinear pillars support heavy stone structures that seem to want to sway like sea weeds?

They can and they do, because Gaudí was an undisputed architectural and artistic genius. He was also a recycler: broken wine bottles, porcelain shards, bits and pieces rejected from factories and other found objects were never too humble to be embedded as decorations into the walls of his magnificent structures. He was also a social visionary. There isn`t a single house that resembles another one in his housing project for factory workers. Gaudí, unlike the Bauhaus movement architects who strongly believed that form must follow function, was obviously trying to compensate for the soullessness of the industrial era.

If there are viewers who fail to be moved by this film it means that they are square and rigid unlike Gaudi’s sublime and visionary architecture.