Ainsi, la première chose que la peste apporta à nos concitoyens fut l’exil. Et le narrateur est persuadé qu’il peut écrire ici, au nom de tous, ce que lui-même a éprouvé alors, puisqu’il l’a éprouvé en même temps que beaucoup de nos concitoyens.

Albert Camus, La Peste

March 20, Friday

We’ve been in lockdown now since last Monday. It started slowly. I tried to go to the Cinéma du Parc on Sunday evening and found it closed. Couldn’t go to church in the morning as services were cancelled and I was glad somehow because that was one less thing I had to do. On Monday I found all cinemas and shows were closed till further notice. Schools and universities have been closed for more than a week, libraries for almost two.

So we wait at home. I’m not dependent on a paycheck – I’m over sixty-five – and I’m not afraid. For reasons I can’t explain, I don’t think I’ll catch COVID-19. There is nothing else on the news and almost nothing in the papers.

I told myself when I first felt the world close in around me, I’m going to use this time to catch up on everything I want to do. And write. I wanted to write something longer and more personal – an affair in psychiatry from long ago – but to write well I have to have a time and a place. I can’t find either. Then I thought, write about our collective trauma, COVID-19. Because writing is always about pushing back the things you can’t control.

March 23, Monday

Late last night I started reading La Peste, Camus. I read it once before, almost thirty years ago, for a private French course with an out-of-work journalist. I picked up an old battered copy in a second-hand bookshop. I’ve kept it through several moves.

This time I read La Peste in French because it’s the only copy I have. Or maybe I like to feel important.

It’s set in Oran, then a department of France, in the 1940s. Oran, Camus tells us, was a city without beauty or shades of meaning, an ordinary city, ugly, it has to be said, with its back turned to the sea. It was a city without pigeons, or gardens or trees. Its inhabitants lived to make money and to gratify simple desires, for love, amusement or comfort. After the plague was over, all agreed that events were out of place there.

Montréal has parks and trees, not many pigeons but sparrows, robins, blue jays, starlings, woodpeckers and cardinals, and countless gardens. It’s a city of neighbourhoods, each with its own assortment of family homes. Once you’ve lived here a while, you can guess who lives where or who used to live where, just by looking at the houses from the outside. Front walks and separate garages mean (or once meant) English; balconies and porches mean French; white or yellow brick probably means Italian. Montréal is a city where people are proud of their differences. Probably they don’t think a lot about money, but they do think about what they share with people in the next house or the next suburb, and sometimes what they don’t. They think a lot about rights.

Now it’s as if that complicated patchwork of history and culture has been taken away. There’s only one message on radio and TV, and that’s COVID – how fast it’s spreading, how close it is to us. We’re not supposed to go anywhere anyway, and we have nothing to do but listen. I walk around the local park or down the street and it’s as if there’s only one neighbourhood, and one street, and that’s here. Here is an eerie silence without traffic noise or ringing footsteps or the sound of people talking louder than they should. Garbage trucks pass at their appointed times and then the silence falls again.

I look out on the garden and it’s almost spring. There’s a hint of life in everything that grows, but all I feel is stillness. It’s as if I’m the last woman alive. Reading La Peste, I throw myself into the void.

March 24, Tuesday

Still nothing is happening. The shops are half-empty and on the main road, the few cars and buses travel singly. I send a few emails. I receive emails from people I’d never dreamt of hearing from – the President of Loblaws, the CEO of Hydro Québec. This virus has the power to change the smallest details of my everyday life. Yet I am well. I eat, sleep, read, write, and the restrictions multiply. After cinemas, theatres and concert halls, they close shopping malls, parks, now small businesses and all stores except grocery stores, supermarkets, pharmacies, pet stores, hardware stores.

We have a new language that justifies the closures and tells us how to act: social distancing, essential businesses, congregating in groups, respecting the guidelines, frontline workers, flattening the curve. When I first heard these phrases, I didn’t know exactly what they meant but I figured them out from what else I knew; and now when I go to the supermarket or the pharmacy or walk down the local shopping street, I have an explanation for the changes. I know why we are chivvied into lines, why I can’t put my points card or debit card into the hand of the cashier, why so few stores are open, why all the FOR RENT signs. I’ve become part of the new order. I shuffle my way through.

March 27, Friday

Because I hear so many statistics, I start looking them up on the Internet – La Presse, The New York Times and a website I found called worldometer. It gives daily figures, ranking countries according to the number of cases.

On March 18, there were 200,000 cases worldwide and 8,000 deaths. Canada had 100 new cases every day. By March 26, there were 492,085 cases worldwide and 22,176 deaths. In Canada there were 3,409 cases and 36 deaths. Globometer gave a tentative global mortality rate of 3%. The WHO estimate for March 3 (death rate) was 3.46%.

I began calculating my own death rates for different countries, but it didn’t take long for me to see that not everyone who will die has died, so that particular statistic means very little. Soon afterwards I asked myself, are reported cases tested cases? Probably. Reporting also has to play a part. On March 26, Russia had 840 reported cases and 3 deaths.

Saw a police car this morning on my way back from the laundromat, driving around looking for signs of trouble.

March 28, Saturday

They told us yesterday we’re entering a new phase: we’re at the beginning of the steep rise that will lead to the peak. A long speech on CBC radio after 4:00 p.m. yesterday from Mayor Valérie Plante, first in French and then in English. This is not a lockdown, not yesterday and not today. The bridges will stay open, but we should stay home. I don’t think it’s an order, but it’s a strong recommendation, and we are told not to go out of our area, especially not the western part of the city. A man, I believe the deputy director of public health for the city, tells us there is community transmission. The reason is the “snowbirds” – the people who didn’t go into isolation when they came back from the States or the South.

The forecast was for a sunny day, but it’s grey cloud cover and cold. I planned on going on the bus to Rosemount, to take a break from myself and look for local colour for the longer essay I want to write. The first scene would be on the corner of Boulevard Rosemont and Avenue des Érables. I tell myself I don’t want to feel more shut in than I do already, unable to write because I couldn’t leave the house. I tell myself I’ll go anyway, though I’m nervous. Can they try to stop me – the police – if they see me walking alone? On the other hand, if I go later, the risk will be greater because the virus is spreading. I decide to go, but I’ll stay apart.

The streets of Rosemount are desolate. I see one man, one woman, and it’s hard to know if they’re going somewhere or just using up time. Everything is shut: houses, stores, a cinema. It’s an area that’s become very chic with storefront windows displaying baby clothes and original home furnishings. On Boulevard Rosemont, a young man with a backpack and worn clothes asks me for change, and I don’t give it. Why not? Because I’m alone and he’s alone and if he did try to grab my purse, there wouldn’t be anyone around to help me. Aloneness breeds aloneness and an obstinate hardness of heart. I keep walking, pass someone who looks less in need.

I’ve begun Chapter 2 of La Peste. The plague has been declared and the gates of the city are closed. The residents of Oran are prisoners, and like most prisoners, time has become meaningless for them. They can’t live for their future release (and in the meantime focus all their strength and courage on surviving their imprisonment), because they’re sure that they’ll find out later on that their release date has been changed. They can’t live in the past, because thinking about the past brings only the taste of regret, and they know they can change nothing. They therefore live in a useless, floating present, wanting their old lives back.

We are more like people under relaxed house arrest. But like the people of Oran, we live without the structure of time. We cannot know how long present circumstances will last, and we don’t know how much of our past we’ll be able to keep once things return to normal. And each person or each family lives with a different loss – with separation from friends, wider family, or a lover, with the cessation of work responsibilities and an identity that goes with work, and without pay. Lives are overturned, but differently, and each person’s life, or each family’s life, is always about managing the disruption. Probably we are more closed in on ourselves and less likely to feel another person’s distress.

March 30, Monday

Towards the beginning of Chapter 2, there is a conversation between the principal character, Bernard Rieux, and a journalist from Paris, Raymond Rambert. Rieux is a doctor caring for plague victims, and Rambert wants a medical certificate stating that he is not infected so that he can leave the city and go in search of the woman he loves. Rieux refuses, first of all because the certificate would prove nothing – Rambert might already be infected but have no symptoms, or might become infected between leaving Rieux’s office and leaving the city – and second, because there are many men in Rambert’s position and he cannot make exceptions. Rambert tells Rieux that he denies their shared humanity and forgets that he is also responsible for individuals and their happiness. He accuses Rieux of speaking the language of abstraction.

Later Rieux sees that this is true. He is no longer moved by the cries of his patients or the pleas of their families. He enforces rules and follows procedures; he stands by while the police and paramedics forcibly remove patients from their homes. He feels no pity, and at the end of the day, his indifference is a consolation for the pain and suffering he has witnessed.

Rieux does not sign the certificate for Rambert. Soon afterwards he joins a team of volunteers organizing emergency services for the sick and dying. Later still, Rambert stops trying to escape the city and joins the volunteers.

March 31, Tuesday

What I miss most is news. I open up La Presse online and there are no new stories, only one short paragraph on COVID. Journalists have been laid off or put on reduced pay.

Now the US is the epicentre of the pandemic, especially New York. China has come out of it fairly well and its citizens are slowly getting back to work.

Later: I hear on the radio that the number of new cases is doubling every day in Canada. I don’t go on worldometer.

April 1, Wednesday

Over 2,000 cases in Québec. So I did check the figures. Went out yesterday, down to Avenue Mont-Royal on a clear, cold spring day. On the Plateau there are more people on the streets than here, some older than I am, and almost all smile as you go by. Then last night I thought I might have the virus – slight fever, slight nausea. But it lifted, then I coughed.

Worldometer, 01-04:

Total cases worldwide: 882,068; deaths 44,136

Canada: total cases, 8,672; deaths, 101

April 3, Friday

I turn on the radio just before 2:00 p.m. and already it’s the barrage of statistics. Legault is still speaking – or is it Arruda? It’s in translation. There are now 63 deaths in Québec attributed to the Coronavirus, but the increase compared to yesterday’s is less alarming than it seems, as yesterday there were cases under review. At 2:00 p.m. Doug Ford says that there could be between three and fifteen thousand deaths in Ontario, 600 deaths. Without public health measures, there could be as many as 100,000 deaths.

April 4, Saturday

This morning’s news: the next week and the next month will tell us if the increase in cases is beginning to slow. They’re talking about perhaps lifting restrictions in June.

But it is scary. After I got home last week from Rosemount, I realized that the stickiness I’ve felt in my throat for the last couple of days could be a sore throat. Later that day I looked in the mirror and saw red cheeks, as if I’d just come in from cold air. I had a slight fever, less than one degree, 97.1 Fahrenheit. But I slept, lighter of heart, because I’d been out earlier. Fever comes and goes. I don’t remember other illnesses being like this. Usually there’s a certain point where you know you’re sick, and if you’re at home you go to bed and hope to sleep it off. Maybe you can’t, but that’s because you get worse, and then the sickness – nausea, giddiness, stomach pain – blocks out worry and the effort to fight it off. This time I just don’t know. One minute I’m sure I have the virus and the next minute I think I don’t. I sleep, only to wake in darkness, knowing I’m alone.

April 6, Monday afternoon

I have one more chapter of La Peste to read. At first it wasn’t easy to follow. I couldn’t always remember who was who, and I got lost in the long descriptions of the mood in Oran. But after the conversation between Dr. Rieux and Rambert, a story starts to emerge. Each character becomes involved in the life of the city, and you follow that person through the year of the plague. Which is not to say that everyone in the novel does good – one person probably does harm because he trades on the black market – but everyone lives a life and is changed by what he does.

Towards the end a new character appears: death, or the plague, or the scourge (le fléau) or later, evil. All tighten their grip on the city and all are one and the same.

April 8, Wednesday

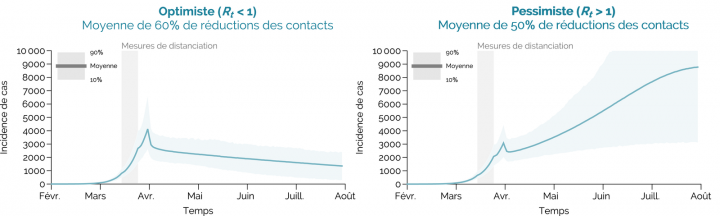

Finished La Peste yesterday. Mr. Legault and Dr. Arruda released their projections for the month (published April 7):

pessimistic projection: cases, 59,845; deaths, 8,860

optimistic projection: cases, 29,212; deaths, 1,263

As the story draws to a close, the virus weakens; the sick begin to recover and the rats reappear. The authorities declare the plague as good as over, and after some delay, the gates are opened and the residents of Oran are reunited with lovers and family. But Bernard Rieux loses the two people he loved most, his wife, who dies of an unnamed illness, and his closest friend, who dies of the plague. He knows then that the plague will never be over for him; he knows as well that he will go on fighting, without hope and without inner peace. Rieux understands what other people do not: that the plague can always return, even in the midst of happiness and celebration, and even when victory seems assured.

April 13, Easter Monday

Main news over the weekend, deaths in seniors’ homes and long-term care. Thirty-one people died in one residence in a little over two weeks, five from COVID-19.

May 12, Tuesday

Today’s news on CBC, a report released on Friday by the Québec Public Health Institute (the INSPQ), and another prediction: if Legault continues with his plan to reopen schools and businesses in Greater Montréal later this month, there will be an additional 10,000 cases in Montréal by the end of June, an average of 150 deaths a day in July. This is excluding deaths in long-term care. The point: reopening should be deferred.

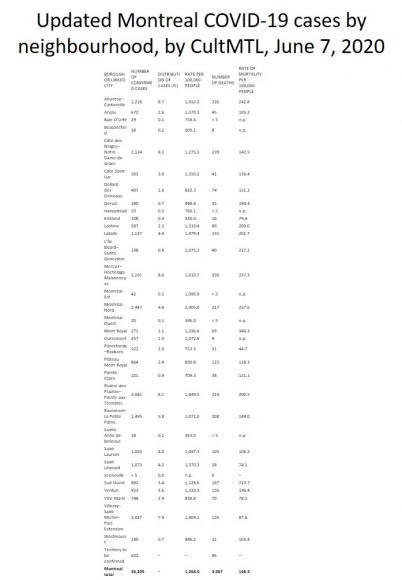

This isn’t the whole picture: over half the deaths in Canada are in Québec (5,169 in Canada, 3,013 in Québec; over half the deaths in Québec are in Montréal (1,919). Not just in Montréal, but predominantly in Montréal North, Rivière des Prairies, Villeray, Park Extension and Lachine – neighbourhoods where there is greater overcrowding, where people have no choice but to go to work, where they use public transport and travel on company buses, and where they cannot escape infection. We’re living in a city more sharply divided along economic lines than before the virus hit, and I wonder if this will be the final message we take from the pandemic – that the costs are not equally shared.