Explicitly sexy?

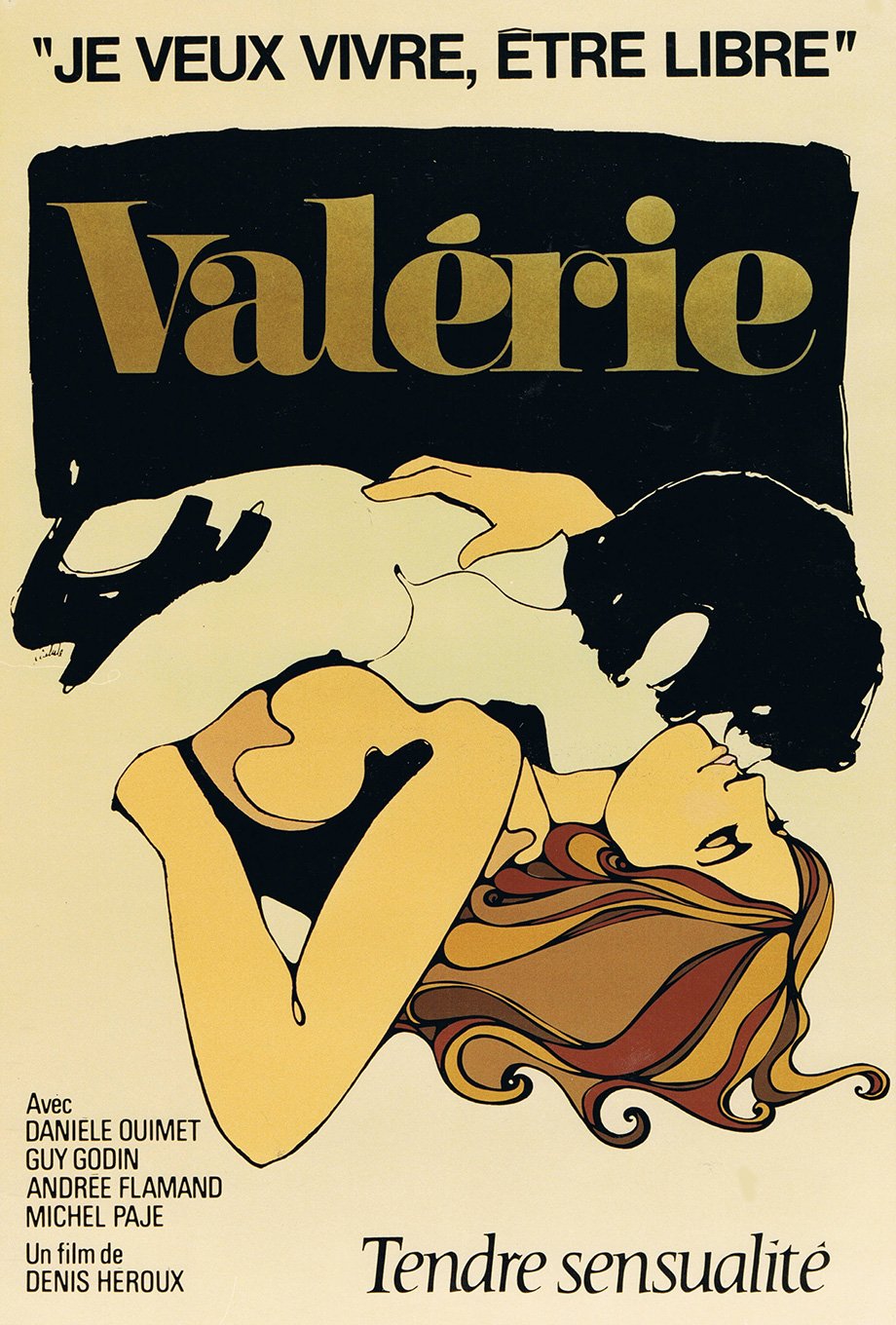

Like emanating from the soft-core industry, the B-movie distributors-turned-producers John Dunning and André Link‘s Cinépix in Montreal. Cinépix became synonymous with Maple Porn sexploitation genre — producing Valérie with Daniele Ouimet (Denis Héroux, 1968), La Pomme, la queue et les pépins (Claude Fournier, 1974) and Après-ski (Roger Cardinal, 1971). Dunning and Link’s pseudonyms created and produced the Ilsa-the-Nazi character and the made-in-Canada, Ilsa: Siberian Tigeress (1977).

Cinépix is also credited for producing auteur and emerging filmmakers: Gilles Carle’s La tête de Normande St-Onge (1975), Denys Arcand’s Gina (1975), early Cronenberg’s Shivers (1975) and Rabid (1977). Oh yeah, Ivan Reitman’s early Canadian films.

Or, implicit brainy sexiness?

Like the high-brow titillating aesthetic of Atom Egoyan or David Cronenberg? Or quirky — the oneiric retro sensibility of Guy Maddin films, explicit nympho in Saddest Music in the World (2003) and sexually repressed in Careful (1992), Brand on the Brain (2011). Fellow Winnipeg filmmaker John Paizs’ ironic Springtime in Greenland (1981) has suburban backyard pool diving competition including male physiques which lend to homoerotism, while parodying “sexy” in speedo.

Read More

- Issue: Film Aesthetics: Are Canadian films sexy?

- New Voices in Canadian Cinema: Montreal Edition — Aonan Yang, Diego Rivera Kohn, and Shahab Mihandoust in conversation with Federico Hidalgo

- “The end of immigration?” –The film

- Filmmaking in Canada: Culture or Coma?

Or, visually sexy?

The kinetic energy of the experimental shorts of Norman McLaren, Michael Snow or his wife, Joyce Wieland and Ann Marie Fleming? French film critic and realism proponent, André Bazin dismissed shorts of being “of insignificant crap.” Or NFB’s large body of documentaries, shorts or animation where past international acclaim makes Canadian film different and desirable except to our unsexy culturally stunted politicians? Or truly independent Larry Kent observational films in his Vancouver trilogy in the 1960s: Bitter Ash (1963), Sweet Substitute (1964), When Tomorrow Dies (1965) and later banned-in-Québec, High (1967)? How about Allen King’s Married Couple (1969)?

Being an independent film, though, isn’t enough for sexiness, if we look at the Crawleys who always worked outside the NFB system. Meanwhile, inside the system, NFB also sponsored great films that have indie aesthetic besides Norman McLaren’s animated painterly shorts and Arthur Lipsett’s shorts like Very Nice, Very Nice (1962), it failed to promote Don Owen’s feature about teenage rejection of suburban hell, Nobody Waved Goodbye (1964).

The Oscars seem to reward NFB animation, while only non-English language films can represent Canada in the Foreign Film category which naturally garners space for Québécois French-language films with the exception of the Inuktitut language film, Atanarjuak, The Fast Runner (Zacharias Kunuk, 2001). Films about the Inuit are surely exotic ever since American Flaherty’s Nanook of The North (1922), but are they sexy to non-Orientalist eyes?

Or hot as in current, timely and newly touted directors? Xavier Dolan can certainly be considered desirable on the international festival circuit along with Denis Villeneuve and Philippe Falardeau.

Québec films, be them popular or auteur, have always found an audience in Québec

Or does it mean sexy, as in popular and mass appeal? American directed in Florida yet still considered Canadian film, Porky’s (1982) used to be Canada’s biggest grossing film until unseated by Bon Cop, Bad Cop (2006). Porky’s wasn’t the first Canadian teen sex comedy. Meatballs (1979) preceded it and even though directed by Canadian Ivan Reitman and shot in Canada, it is not considered wholly Canadian.

Québec films, be them popular or auteur, have always found an audience in Québec due to language while English-Canadian Cinema seems to be snubbed by Canadians who have an easier access to American major studio releases, and this fact relegates Canadian auteur filmmaking to elitist status. Unlike Canadian Literature which has been cemented as a formidable cultural industry (easier to produce), its cinematic counterpart finds it hard to get a footing at home.

No whiff

You wouldn’t find any whiff of sexy in the origins of Canadian early cinema. The first Canadian feature about the Acadian heroine, Evangeline (1913), was lost forever. Trenton Studios that produced the First World War reenactment film Carry on Sergeant (1928) had a wartime love affair with French barmaid storyline. Certainly, the first Canadian actors in early cinema, with exports like Norma Shearer, Mary Pickford and Marie Dressler, including New Brunswick raised studio founder, Louis B. Meyer and Ontario-born, Jack Warner were famous – but all had nothing to do with our national cinema. Similarly, in the not exactly Canadian or salacious category, Eastern Townships born (and one-time Pointe-aux-trembles resident) Mack Sennett, famous for his Keystone Kops, was parading Sennett Bathing Beauties (1915 serial) where Hollywood starlets donned swimsuits posing at beauty contests in California.

Is nude rude? Always so inquisitive and polite

But an early sense of Canada’s edginess with skin began with Back to God’s Country (1919) where Nell Shipman’s heroine, Dolores Lebeau emerges from the forest pool nude, albeit in a bodysuit, in the great outdoors, the epitome of Canada’s iconography. The nude scene, re-written in the film adaptation by Nell Shipman and American novelist Curwood, from whom the script was sourced, was intentionally used to draw in male viewers with the marketing of the film with the tag, “Is nude rude?” Dolores is the centre of the voyeuristic male gaze and object of desire by the would-be rapist spying from afar as well as the audience viewer. The film is not as racy as Hedy Lamarr’s later Czech film Extase (1933) which had more fun in the buff with no bodysuit and an explicit orgasm. Both had full frontal nudity, imagined or not, in a naturalistic setting, though Nell appeared “nude” once and even as co-screenwriter/actress bought into that vision of female objectification while Lamarr’s nudity pushed the boundaries with historic firsts.

The other woman in the film, the Inuit woman, after initially rebuffing a sailor’s advances, receives soap which implies colonial exchange for sexual services rendered. She is ridiculed for attempting to eat it which adds to the film’s racist treatment of “the Chinaman” and Métis males.

Margaret Attwood and Northrop Frye have outlined what makes Canadian semiotics in regards to literature, ideas which can certainly be transposed to cinema. Attwood advances the ‘idea of survival’, while Frye mentions dislocation in the landscape (pastoral myth), irony, identity as a centrifugal force, theme of descent, and geography of the global village.

Canada’s iconography often gets compared to its colonial counterpart Australia in terms of political, aboriginal, multicultural history / histories , the harshness of their respective extreme climates and landscapes, with the ‘idea of the Bush’ for Australia’s literature and cinema.

The first thing I conjured when thinking about sexy and Canadian film was the title of Katherine Monk’s popular primer book (2001) and subsequent documentary (2005), Weird Sex and Snowshoes and Other Canadian Phenomena, succinctly categorizing obvious Canadian themes, symbols and aesthetic. For a film to be deemed Canadian, according to Monk, motifs must include landscape, twin imagery, missing parent, road to nowhere, survivor guilt, outsider, passive males, potent females, identity issues and weird sex. Snow must be there for snowshoes to tread on – making its debut in Back to God’s Country (1919), and the title/subject in Michel Brault’s and Gilles Groulx’s Les Raquetteurs (1958).

Sarah Polley’s Away From Her (2006), based on a short story from Alice Munro, deals with the complication that Alzheimer has on couples

Identity issues presupposes sexuality in Canadian film producing a large body of Queer Cinema: À tout prendre (Claude Jutra, 1964), Ten Cents a Dance : Parallax (Midi Onodera, 1985) and Skin Deep (Midi Onodera, 1995), Lillies (John Greyson, 1996), The Hanging Garden (American Thom Fitzgerald, 1997), Kissed (Montréaler Lynne Stopkewich, 1996), Better than Chocolate (Anne Wheeler, 1999), Panic Bodies (Mike Hoolboom , 1998) and the films of Swiss-born Léa Pool (Anne Tristler, 1986, À corps perdu (1988), Lost and Delirious, 2001) and video installations of Richard Fung.

Older adults’ sexuality is portrayed in Sarah Polley’s Away From Her (2006), based on a short story from Alice Munro, deals with the complication that Alzheimer has on couples. There are snowshoes in that film, too, though the film comes after the publication of Monk’s book.

Weird can describe the collection of formaldehyde phalli in Margaret’s Museum (1995), based on a novel about mining community in Glace Bay, Nova Scotia.

Maybe the Canadian brand of pasty sexiness which seeps through its literature and cinema can be explained by Pierre Berton’s oft-cited quote: “A Canadian is someone who can make love in a canoe without tipping.” There you have it. Nature and sex. The Great Outdoors and unconventionally tricky en plus.

Further Reading

- Paul Corupe’s Canuxploitation website on Canada’s contribution to the world of exploitation, b-movies, kitsch and horror. Québec Maple Porn http://www.canuxploitation.com/article/cochons.html

- Christopher Gittings. Alterity and Nation: Screening Race, Sex, Gender and Ethnicity in Back to God’s Country, Canadian Journal of Film Studies, Vol. 5, No.2.

- Bill Marshall. Québec National Cinema

- Peter Morris. Embattled Shadows: A History of Canadian Cinema 1895-1939