Langston Hughes (1902-1967) was the best-known Afro-American poet of the 20th century. His work also ranged from novels, to plays, to books written for children. And his newspaper columns in The New York Post were sources of amusement and insight for thousands of readers from all backgrounds. At the root of his writing, though, were his poems, and the pulse of black music, and especially jazz that for Hughes remained an idiom of continual protest.

In this issue of Montreal Serai we are looking at the connection between music and the spirit of rebellion – so we asked Montreal writer Mara Grey to give us her view of Langston Hughes and she has sent us this reflection – “The Jazz Voice.”

The Jazz Voice

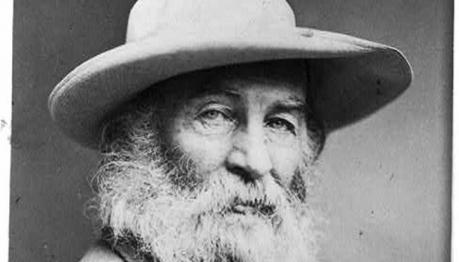

Langston Hughes: a portrait of the other

By Mara Grey

I. Langston Hughes–Spokesman of a People

I, too, sing America.

` I am the darker brother.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . .

I, too, am America

–“I, Too, Sing America” Langston Hughes

In the poetry of Langston Hughes the subject, the language, the voices and the form are overdetermined by black idiom and the rhythmic patterns of the call-and- response of the sermon, the blues, the polyphonic instrumentation of Jazz. Sascha Feinstein in Jazz Poetry says that when Hughes “began to find his poetic voice” that it was “nurtured by the sounds of the blues and jazz.” Hughes himself in his autobiographies speaks of his wanderings in Harlem listening to the sounds of the city. And Onwuchekwa Jamie states that “Hughes has anchored his work in Afro-American oral tradition, thereby serving the vital function of cultural transmission. His utilization of black musical forms–jazz, blues, spirituals, gospel, sermons–is the most comprehensive and profound in the history of Afro-American literature.” Hughes’ poetic language, particularly its vernacular, is an incorporation and manifestation of what Houston Baker Jr. calls the “blues matrix.”

The poetic persona and subject represented in Langston Hughes’ poetry is the repressed and marginalized other that perturbs the very construct it seeks to re-present. This is made obvious in the very opening of “I, Too, Sing America” in which Hughes enunciates his poetic persona echoing Walt Whitman and reinstating the other.

On the one hand, the multiple voices the reader hears in Hughes’ poetry foreground the poet as an “I”; as a lyrical and prophetic voice; as the spokesman, the poet of the people in the tradition of Walt Whitman. The critic Donald B. Gibson makes the parallel between Whitman and Hughes explicit: “Both adopt personae, preferring to speak in voices other than their own. They are social poets in the sense that they rarely write about their private, subjective matters, about the workings of the inner recesses of their own minds.” On the other hand, Hughes’ poetic personae encompass a polyphony of created bodied-voices — sometimes speaking in monologue, sometimes in dialogue, and sometimes in chorus, in a lyrical, dramatic, or narrative form — that reflect the poet as a dramaturge, an “arranger,” and thus spill over the notion of a unified poetic identity.

In one hand

I hold tragedy

And in the other

Comedy––

Masks for the Soul.

(“The Jester”)

Hughes creates strong physical and emotional portraits through letting the other voices speak/sing their joys, their sorrow songs as he no doubt heard them walking the streets of Harlem. Sascha Feinstein states that “Hughes soon recognized the importance of uniting poetry with Jazz. His goal: that poetry would offer respectability to Jazz and that the music would in turn give poetry a larger audience.” That is to say, a language that is expressive of the Afro-American experience, that has its roots in the vestiges of Africanism, and the legacy of slavery. It is a language appropriated and given voice, that reflects the psyche and the ethos of a people.

Because my mouth

Is wide with laughter

You do not hear

My inner cry;

Because my feet

Are gay with dancing

You do not know

I die.

(“Minstrel Man”)

In giving voice to the minstrel, Langston Hughes’ poem spotlights the Black Man’s humanity which the black-face entertainment mask has denied him in American history. The poetic personae Hughes deploys are representations of the voces populi through which the poet both locates and represents the Afro-American in the past and the present, in Africa, in the American South and the urban North, to the tune and the tempo of the twenties, The Jazz Age. Hughes outlined his approach in his own words: “But jazz to me is one of the inherent expressions of Negro life in America: the eternal tom-tom beating in the Negro soul––tom-tom of revolt against weariness in a white world, a world of subway trains, and work, work, work; the tom-tom of joy and laughter, and pain swallowed in a smile.”

R. Baxter Miller, in The Art and Imagination of Langston Hughes, has described how successfully Hughes conveyed his vision: “He certainly earned his claim to the title of ‘People’s Poet’-for he was indeed one of the most loved and accessible of all American authors.” In “The Negro Speaks of Rivers” Hughes foregrounds his poetic persona as the inheritor of history and civilization: “My soul has grown deep like the rivers.” This, his first published poem, constitutes an enunciation of the poet, (singer, prophet) who, like Walt Whitman before him, sings of America, but who unlike him, is Black: “I am a Negro:/ Black as the night is black,/ Black like the depths of my Africa.” But also, “I am the American heartbreak/ Rock on which Freedom/ Stumps its toe-” (“American Heartbreak”).

II. A New Lyrical Voice

While Hughes’ poetic persona as the singer reflects the lyrical tradition, yet the structure and voice of that tradition is refigured; its signification altered, shifting its perspective and its balance of power from white to black: “Dark ones of Africa, / I bring you my songs/ To sing on the Georgia roads” ( “Sun Song” ). This is the persona that carries the weight of history and prophecy, of the dream of freedom and change.

. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . My hands!

My dark hands!

Break through the wall!

Find my dream!

Help me to shatter this darkness,

To smash this night,

To break this shadow

Into a thousand lights of sun,

Into a thousand whirling dreams

Of sun!

(“As I Grew Older” )

The voice in these poems is not speaking for himself alone. It is rather the collective voice of a people striving to define themselves against a background of political and social oppression. Larry Neal, in his essay “Langston Hughes: Black America’s Poet Laureate”, states: “[His] lyric gestures towards the epic form in that it attempts to express the collective ethos of a profoundly spiritual people. Langston’s career like James Joyce’s, especially centers around his attempt to interpret the ‘soul’ of his race.”

Hughes’ poetic persona like that of the other Modernists is protean, from the lyric voice that illuminates what was previously dark (both historically and existentially), to a re-appropriation of the voices of the community like that of the preacher in “Sunday Morning Prophecy” whose oralizing cadences are powerfully rendered: “Oh-ooo-oo-o! / Then my friends! Oh, then! Oh, then!/ What will you do?”; or the many other ones that speak in the dramatic monologues and dialogues: the “high and low” representations of the Afro-American community. Blynden Jackson has stressed how Hughes gathered up all his first-hand experiences: “Through many years he saw enough to be a leading interpreter of the Negro in twentieth-century America and twentieth-century literature.” A poem like “Mother to Son,” remarks Richard Barksdale, and “others of this same category indicate that Hughes very early in his career had developed the ability to project himself imaginatively into many dramatic roles.” Thus, the poet speaks in a polyphony of voices, most often in counterpoint to other voices. Sometimes a poem is like a snap-shot, a riff that captures a low-down moment in the life of an indistinct “I”: “Here I sit/ With my shoes mismated./ Lawdy-mercy!/ I’s frustrated!” (“Bad Morning”). Sometimes, Hughes manipulates the speakers to reveal their inflated egos and shortcomings as in “As Befits a Man” or “Sylvester’s Dying Bed.” Even though the speaking voice in these poems is other than the poet’s, his presence is nevertheless felt like the shadow of the dramaturge off-stage, or perhaps more appropriately like a bandleader, like the great Duke Ellington, harmonizing the disparate voices, arranging, marking where the solos come in, working the harmony and the dissonance. Humor, irony, satire are the tools which Hughes has honed to reflect a fine tune, as in “Morning After.” Such poems reflect the sharp wit and syncopated rhythm of the home-down blues narrative patterns. For example, “signifyin’” [“signifying” in afro-american popular culture is a way of constructing elaborate verbal ruses to amuse or confuse a verbal opponent] on the implicit blues line–– what’s wrong with you baby–– with the answer in the opening lines of the poem: “I was so sick last night I / Didn’t hardly know my mind.” As in a classical blues form, the line is repeated in variation. The whole of the poem is characteristic of the blues: a simple direct heartfelt expression of what Wallace Stevens calls the malady of the quotidian. And Jemie in her study of Langston Hughes says it best: “In Hughes’ poetry, the oral tradition is perhaps strongest in those poems modeled on black music–the jazz and blues poems….black music [envisioned] as a paradigm of the human experience: ‘The rhythm of life /Is a jazz rhythm, / Honey.’ ”

III. Jazz Polyphony

Hughes is the interpreter of the lives of the common Black Folk, their thoughts and habits and dreams, their struggle. The multiplicity of voices of these poems are those of the ordinary men and women of Harlem, the “low-down” folk, whom Hughes represents unsentimentally in their wretchedness, their sadness and their humor. In some of these poems, like “Early Evening Quarrel,” Hughes employs the techniques of street poetry such as rapping and signifyin’ to give a double edge of signification to the representation of woman/man relationships, while simultaneously evoking a blues duet of the done-me wrong genre. In these poems the poet’s voice is absent, but his presence is manifest in the arrangement of lines and reflection of character through the speaking voice. The legacy of aural tradition asks that the poet integrate his voice with the voices of others. Ralph Ellison in Shadow and Act succinctly and eloquently represents the scope and significance of the jazz paradigm that is manifest in the poetry of Langston Hughes.

For true jazz is an art of individual assertion within and against the group. Each true jazz moment (as distinct from the uninspired commercial performance) springs from a contest in which each artist challenges all the rest, each solo flight, or improvisation, represents (like the successive canvases of a painter) a definition of his identity: as individual, as member of the collectivity and as link in the chain of tradition. Thus, because jazz finds its very life in an endless improvisation upon traditional materials, the jazzman must lose his identity even as he finds it.

Langston Hughes is the quintessential jazz poet whose subject, language, voice, and form coalesce in an adaptation of the jazz aesthetic. Hughes makes this quite clear in his poetic manifesto, “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain”: “But jazz to me is one of the inherent expressions of Negro life in America.” In fact, Hughes identifies Jazz as the major trope, and a vehicle of consciousness: “Let the blare of Negro jazz bands and the bellowing voice of Bessie Smith singing Blues penetrate the closed ears of the colored near-intellectual until they listen and perhaps understand.” In Hughes’ poetry, the influence of Jazz is expressed in the use of varied rhythmic patterns that integrate the repetition and variation, the heavy hearted slow-time-pace of the blues aesthetic with the staccato syncopating urban rhythms of jazz, expressed by the voices that need to speak their subjective pleasure or loss into language. Hughes’ poems, like the jazz tunes and tones they evoke, are deceptively simple; yet, they reflect a stylistic control and sharp vision characteristic of the blues that says whatever it is just so; or the epigram, like those of William Blake, that crystallize a universal theme in a few lines, and reflect an oracular voice.

What happens to a dream deferred?

Does it dry up

like a raisin in the sun?

Or fester like a sore-

And then run?

Does it stink like rotten meat?

Or crust and sugar over-

like a syrupy sweet?

Maybe it just sags

like a heavy load.

Or does it explode?

(“Harlem”)

Looks like what drives me crazy

Don’t have no effect on you-

But I’m gonna keep on at it

Till it drives you crazy, too.

(“Evil”)

The calm,

Cool face of the river

Asked me for a kiss.

(“Suicide Note”)

It is clear that the voice in these poems is representative of the human condition generally, and the black experience particularly; that is to say, black history and culture within the history and culture of America and the world. Sascha Feinstein in his assessment of Hughes states: “in retrospect, Hughes’ earliest publications, including The Weary Blues (l926) and Fine Clothes to the Jew (l927), substantiate his status as the most successful poet from the twenties to achieve a union between poetry and jazz.” Indeed, his poetry is both a composition in blue that underscores the shared human experience that he gives voice to, and a linguistic improvisation that lays down polyrhythmic crossover patterns characteristic of the innovation of Jazz.

Perhaps, it is Hughes’ ability to integrate the complexity of modern life, in all its paradoxical manifestation, into simple poetic expressivity that speaks/ sings truth, that reverberates with implication long after you’ve heard it or read it, the way a well-wrought jazz tune integrates the new rhythms and the old, to tell it like it is without you the listener quite knowing what that is, but feeling it sounds good! Perhaps this is what Jessie Fauset, literary editor of The Crisis, meant in reviewing Hughes’ “The Negro Speaks of Rivers”; “that remote, so elusive quality which permeates most of his work. His poems are warm, exotic, and shot through with color.”

Help me to shatter this darkness,

To smash this night,

To break this shadow

Into a thousand lights of sun,

Into a thousand whirling dreams

Of sun!

(“As I Grew Older”)

This oracular voice that seeks to change the scheme of things through poetry, shifts in tone and attitude in representing the human condition in poems of a later period. It is a voice that reflects a hard stance and a militant tone. This is the voice that calls for political revolution and change. One could argue that there is a double bind in this voice. On the one hand, Hughes, like the Sartrean engaged writer, forges a political persona that speaks in protest, holding up a mirror to reflect the great injustice perpetrated by a racist society. On the other hand, the voice turns on itself in disillusionment, frustration and anger as in the poem “Liars”:

It is we who are liars:

The Pretenders-to-be who are not

And the Pretenders-not-to-be who are.

It is we who use words

As screens for thoughts

And weave dark garments

To cover the naked body

Of the too white Truth.

It is we with the civilized souls

Who are liars.

IV. The Riff, The Be-bop, The Loss, and The Mask

From the chorus to the solo the voices that speak of the loss of hope are particularly poignant in the poems entitled “Montage of a Dream Deferred,” reflecting the American dream gone sour echoed in a dissonant medley of voices: the voices of black kids ‘hanging-out’ on the streets, aware of their fate; their lack of future, their experience of injustice and failed democracy expressed succinctly, on the sharp edge of truth: “Liberty And Justice- / Huh-For All.” These voices are in counterpoint with those of an earlier generation: “One-two-buckle my shoe!” Underneath the contrapuntal play of voices, set side by side, these voices nevertheless disconnect to express a dissonance of values/ideologies which this poem sets up in crystal clarity. The nursery rhyme, and its European origins on the one hand; and on the other hand, the jazz-jive-scat-bop-talk this poem” “frames” as a creative third term; if not as way out for these kids, then an open-ended potential, an either/or, representing a situation on the verge of violence; or violence subsumed in a creative improvisational active participation with the aesthetic and the ethos of the times: bebop (one is reminded of Gwendolyn Brooks’ “We Real Cool”). These epigrammatic, riff-like poems are a portrait of American Black Youth face-to-face with the dream of democracy! In “Children’s Rhymes” Hughes sets up a call-n-response format that makes this point most dramatically.

When I was a chile we used to play,

“One-two-buckle my shoe!”

and things like that. But now, Lord,

listen at them little varmints!

By what sends

the white kids

I ain’t sent:

I know I can’t

be President.

There is two thousand children

in this block, I do believe!

What don’t bug

them white kids

sure bugs me:

We knows everybody

ain’t free!

Some of these young ones is cert’ly bad-

One batted a hard ball right through my window

and my gold fish et the glass.

What’s written down

for white folks

ain’t for us a-tall:

“Liberty And Justice-

Huh-For All.”

Oop-pop-a-da!

Skee! Daddle -de-do!

Be-bop!

Salt’ peanuts!

De-dop!

This poem written in a language that Henry Louis Gates Jr. calls “talkin’ that talk” speaks in two tongues, in vernacular American rhythms and the appropriated bebop jive. The incorporation of these politically inscribed identities of the old and the new is reminiscent, on the one hand, of the passive stance of the Negro advocated by the legacy of Booker T. Washington; and, on the other hand, the confrontational stance of the pre-civil rights demands of the New Negro, already manifest in the Harlem Renaissance, particularly with the second generation artists, the Niggerati, Zora Neal Hurston’s signifyin’ trope. Two parallel dialogues that engage an always already conflicted racial bind, which in a forward-looking glance, call to mind the militancy of a later black aesthetic face-to-face re-play of white and black confrontation in Amiri Baraka’s The Dutchman . Hughes’ poem “Children’s Rhymes” has its own undercurrent of militancy, expressed in a tonal supplement, much like a jazz tune in contrapuntal voices and shifting rhythms subverting, playing against, hopelessness, improvising as survival. Larry Neal’s concept of the poem simply as “score” to be realized comes to mind.

In an assessment of Hughes’ poetic voice one is struck by its chameleon-like transformations, its masked performances, its recuperation and integration of the past; its incorporation of the ethos and aesthetics of jazz into the poetic mode that is at once “new,” and as old as the troubadours; and still older in its oracular/orphic sonority. Charles O. Hartman, speaking of the distinct concepts of voice in his seminal Jazz Text, differentiates between voice as an abstract idea of selfhood (Martin Luther King as a voice in American political history) and the vibrations of air in a particular throat (Martin Luther King’s unmistakable voice). These provide a fitting analogue to the scope of Hughes’ poetic voice. King, the great orator, makes a striking contrast to Hughes the scriptor, to borrow a Poundian trope laced with irony. Both Pound and Hughes were adept at irony, in the very complexity of their position as Modernist poets whose words, in spite of their orality, remained on the page — while Martin Luther King’s voice rose to disperse in the sonority of the dream. It is interesting to note, however, that Hughes poetic identity is elusive, other than what his masks show, and in spite of the autobiographical narratives. Hughes is a poet whose subjectivity is subsumed under the polyphony of the poetic persona. Blynden Jackson in Black Poetry in America puts it this way: “He has an ability to enter into the very cores of existences other than his own…to let his subjects be themselves. He was always disciplined enough not to ‘hog’ their show.”

In Langston Hughes’ poetry the speakers are forever shifting the “masks” of their representations, slipping beyond the boundaries of a unified poetic subjectivity. In his creation of poetic personae the question of subjectivity and representation is always already constrained by the double bind of the “other,” race and gender — hence the double-double bind. Finally, the reader is intrigued by the absence of the gendered sexual self in Hughes’ poetics, (an interesting inquiry on its own), the man behind the ‘mask’ of the poet, who in the very act of voicing desire and poetically constituting presence in a polyphonic dialogic construct, is perhaps sacrificed on the crucible of a dream deferred.

I could tell you,

If I wanted to,

What makes me

What I am.

But I don’t

Really want to––

And you don’t

Give a damn.

(“Impasse”)

The man behind the mask remains a mystery. Langston Hughes’ poetic personae, however, re-instate the other, the marginalized voices of Afro-Americans within the spectrum of poetry in America and the world, and in the words of Henry Louis Gates Jr., Hughes is an artist “signifying black difference.” The range of Hughes’ poetic persona is communal. His is the voice of the prophet, dream spinner, balladeer, minstrel, blues and jazz singer, playing the changes, “playing” language, subverting its field of signification, speaking for and to the “other” through multiple personae that both reveal and conceal the self. As Onwuchekwa Jemie says, “Hughes wears a genial mask that fits so well it is possible to mistake it for his face.”

Looking back at Langston Hughes’ legacy we can see an authentic and heart-felt rendition of jazz in poetry.

And in the poems, once again, as in all the great traditions, poetry and music are one and many — at the same time.

This was an enjoyable discussion of Hughes’ poetry. I do wonder about the convention of capitalizing Black, while writing Afro-American without capitals.