A Bitter Song / Shiʿr-i Talkh

My heart desires a bitter song

more bitter than a Turkish coffee

and the mopish smell of grass,

like my own dark fate,

on one of the cursed summer nights.

Sing for me

a song unsung before,

O friends for hard times,

sing so I can drink

to the health of all unrequited souls in history, and

drink till I’m wasted.

My heart seeks a bitter song

bitter like my acrid fate

bitter like all poets of blank

verses

all remorseful of love.

My heart craves for misty eyes

waters flowing in a deep and dark hollow, as if I were Ali,

a thousand years of rancour buried in me, and

my dry eyes so moistened by blood

that even Siyavash couldn’t help but

sit still, shocked by my sorrows.

My heart demands an elegy.

Freedom / Āzādi

In search of you,

O sib of love,

O freedom,

we arrived

like a northerly wind,

in haste,

among the meadows of melancholy.

We sprinted

towards

a light of pointless thoughts, but

we didn’t know

in the world of

gods, perhaps

humans were

merely a candle

burning

backwards.

Shirabad / Shirābād

Somewhere

between death and resurrection,

when it was time to believe

I turned suspicious of shadows, and amidst violet screams1

I drew a faint sigh of relief. I did not cry.

No smile moved my heart.

My beloveds wore earthy colours.

Their heads, heavy with memories,

couldn’t find a ground to prostrate.

No one cared

for what lay under that grey curse,

for where a tiny bird dropped its egg,2

for whether a fulsome bud was shred into pieces.

Trapped

between death and resurrection,

at the military outpost of Kule Sangi,

near the border of Zahedan,

was a deportee

desperately looking for

a folder of faded citizenship documents

and for a wish

frozen in the inferno of Zahedan.

That space

between death and resurrection

appeared

to a thirsty soul lost deep in

the desert, before mirages

filled the summer,

before the delusion of heavenly

wine set in,

like a prayer without ablution,

the paradise, too, was

a faith lost,

unattainable and unreachable.

That space

between death and resurrection

appeared

in the lilac shade

of a child devoid of an identity card.

It plants seeds along the path

where the wind blows,

where it desires a homeland

that is without milk

that is without prosperity.

Notes

1 The imagery of “violet screams,” Aftab notes, invokes three interrelated references: the painting The Scream (1893) by the Norwegian artist Edvard Munch (1863–1944); an avant-garde poem by Hushang Irani, which is titled “violet scream”; and the sentimental and banal motifs of the Iranian intellectual community.

2 The “tiny bird” is a reference to the Micro Air Vehicle (MAV) that Israel used to bomb Iranian cities during its 12-day war against Iran in 2025.

N.B.: We have used the Encyclopædia Iranica transliteration scheme in our translation and prose.

Afterword

On Knowing and Translating an Iranian Poet

I have known Aftab for more than a decade. We belonged to the same cohort of graduate students at the University of Tehran. We met during an orientation ceremony organized by the university’s International Office. Spotting the only Indian in the house, Aftab came to me and asked, “Are you from India, the land of Gandhi?” At a time when Gandhi was already banished from his own homeland, I was moved to see how deeply invested Aftab was in engaging with the Gandhian philosophy. We became instant friends.

As a foreigner specializing in Persian Studies, I was always too keen to make Iranian friends. For Aftab, however, my friendship was not without challenges. Whenever he was in my company, most Iranians around us would automatically assume that he, too, was a Pakistani like me. Neither Aftab nor I were from Pakistan. As a Balochi person, the cultural otherness of Aftab was rarely invisible in the cosmopolitan circles of Tehran. As an Indian, I was no different from any Pakistani person. Although Aftab was acutely conscious of the cultural optics and identitarian politics in Iran, he never resented my company nor the questioning gaze of his fellow citizens. With good humour and poetry, he brought us all together.

With good humour and poetry, Aftab brought us all together.

We moved away from Tehran after our graduation. We found new vocations in faraway lands. But our conversations on Persian poetry, Sufi literature, Indian culture and political philosophy continued unabated for much of the last decade. When the news of Israel’s war on Iran broke out earlier this year, I grew anxious about the fate of my friends and acquaintances there. I sent a panic message to Aftab inquiring after his well-being. “Our internet is barely functional, but we all are safe and sound,” Aftab hastily replied to me. Two weeks later, on August 1, 2025, after Israel ended its one-sided aggression on Iran, the internet became operational again. A poem titled Shirābād by Aftab showed up on my screen. That poem was more than a revelation to me.

For the first time in over two decades of reading Persian poetry, I was face-to-face with a poem that voiced the political struggles and spiritual crises of marginalized communities residing in the outlying provinces of Sistan and Baluchistan. A poem that exposed the many faces of violence—violence emerging from the outside as much as from within; violence engendered by the so-called sovereign and religious states on the disenfranchised masses; violence perpetuated by the cosmopolitan urbane elite on vernacular provincial communities; and above all, violence against the very ethoi of human rights, social responsibility, care and compassion.

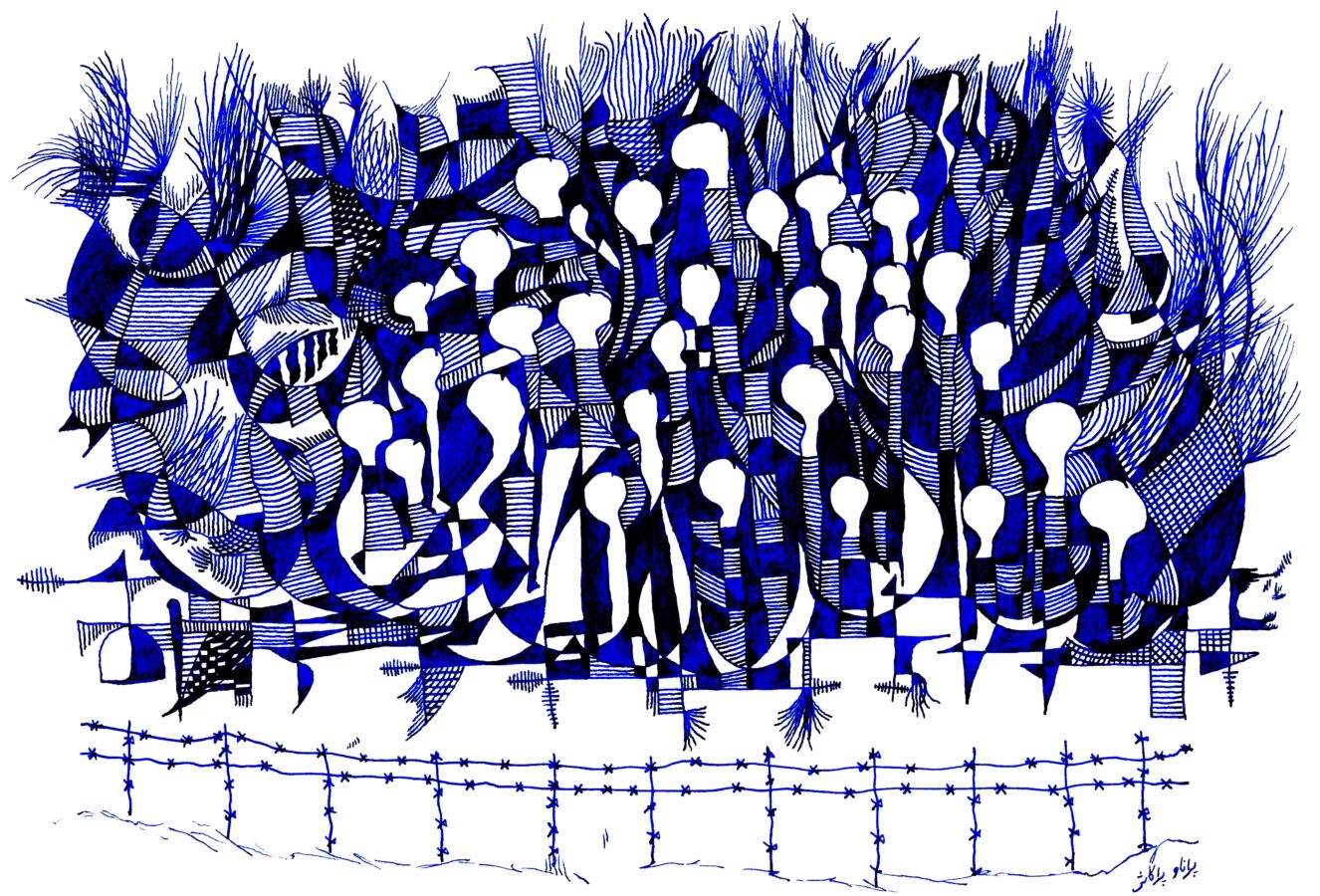

Reflecting on the context of Shirābād, Aftab relates, “After the 12-day war ended, the Iranian government expelled more than one million Afghan refugees, and it has since continued to deport more and more refugees.”

Reflecting on the context of Shirābād, Aftab relates, “After the 12-day war ended, the Iranian government expelled more than one million Afghan refugees, and it has since continued to deport more and more refugees.” One of the local newspapers reported that many Afghan children, who were born and brought up in Iran and who did not have any family members in Afghanistan, were nevertheless deported to Afghanistan for want of citizenship documents. As a human rights lawyer active in the border province of Sistan and Baluchistan, Aftab has time and again witnessed the inconsolable tears of those Afghan children who were about to become homeless and stateless orphans.

A deep sense of compassion in Persian cultures has long been recognized as the ethos of ham-zāt-pendāri, that is, one’s ability to vicariously think and feel like others and therefore empathize with others. Whereas empathy is a cherished virtue for all, it is not uncommon that such an emotional response emerges from a place of privilege. That privileged empathy has remained unseeded in Aftab. His ham-zāt-pendāri emanates from his experience of everyday toil, bodily suffering and physical disability. Several years ago, while driving a car from Shiraz to Chabahar, Aftab was hit by a truck and was left nearly dead on the highway.

To escape the tyranny of a body impaired, he turned to poetry—seeking songs that were as yet unsung…

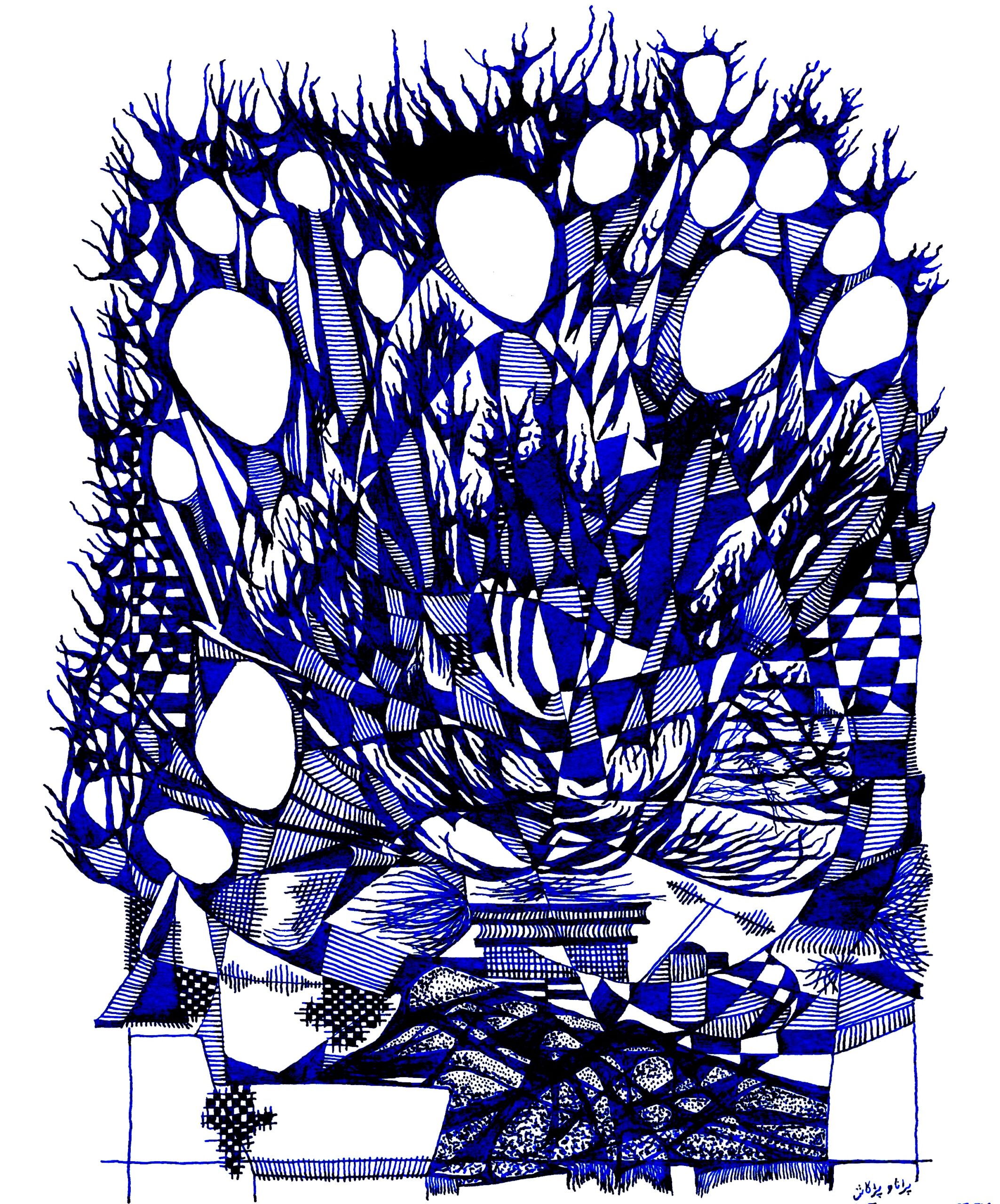

“Many a sound would echo in my ears long after the accident, and the consonants shin and sin played incessantly in my head,” Aftab recounts his struggles to heal from the traumatic accident that left him disabled for life and notes, “The physical pain never really goes away; it merely transitions into a grief perpetually borne by one’s soul.” To escape the tyranny of a body impaired, he turned to poetry—seeking songs that were as yet unsung, and querying elegies that his soul could call its own. Shiʿr-i Talkh came into being thus.

Poetic craft, for Aftab, always inheres in the human condition. The desire to know who we are as sentient beings and the pursuit of a novel poetic form are mutually constitutive endeavours in his life. Elaborating upon the background of Āzādi, Aftab writes, “In the last two centuries, Middle Eastern intellectuals—in the name of advancement and to break free of their age-old traditions—have regularly turned to Western cultures for refashioning their understanding of two deep-seated human desires: love and freedom.” Unbeknownst to them—as Aftab reckons—are the many trappings of freedom that even the most cosmopolitan societies fail to notice and disengage. As his poetic persona desperately searches for their beloved in Āzādi, their hasty approach towards self-awareness and self-criticism arises from and gives rise to the flow of poetic images and metaphors. His unravelling of existential truth and his practice of poetic craft are mutually liberating.

Persian poetry couldn’t be more free, more deep, more agonizing and more beautiful.

Pranav Prakash