An eclectic collection

As someone who grew up in India, many of these stories were already familiar to me, like the one about the great Mughal emperor Akbar and his delightful anecdotes with his witty and very wise courtier Birbal and the many tales of the Hindu gods and goddesses, almost human-like with their conflicts, foibles and passions.

The book is an eclectic collection of enchanting and engaging stories that have at their hearts a key culinary ingredient or food preparation. At the end of each story is a detailed recipe for the dish the story mentions. The tales encompass a wide spectrum, ranging from the macabre—such as the fisherman who makes a deadly pact with a sorceress—to the humorous—like the tales of Akbar and Birbal—and the tragic tale of a young mother dealing with grief.

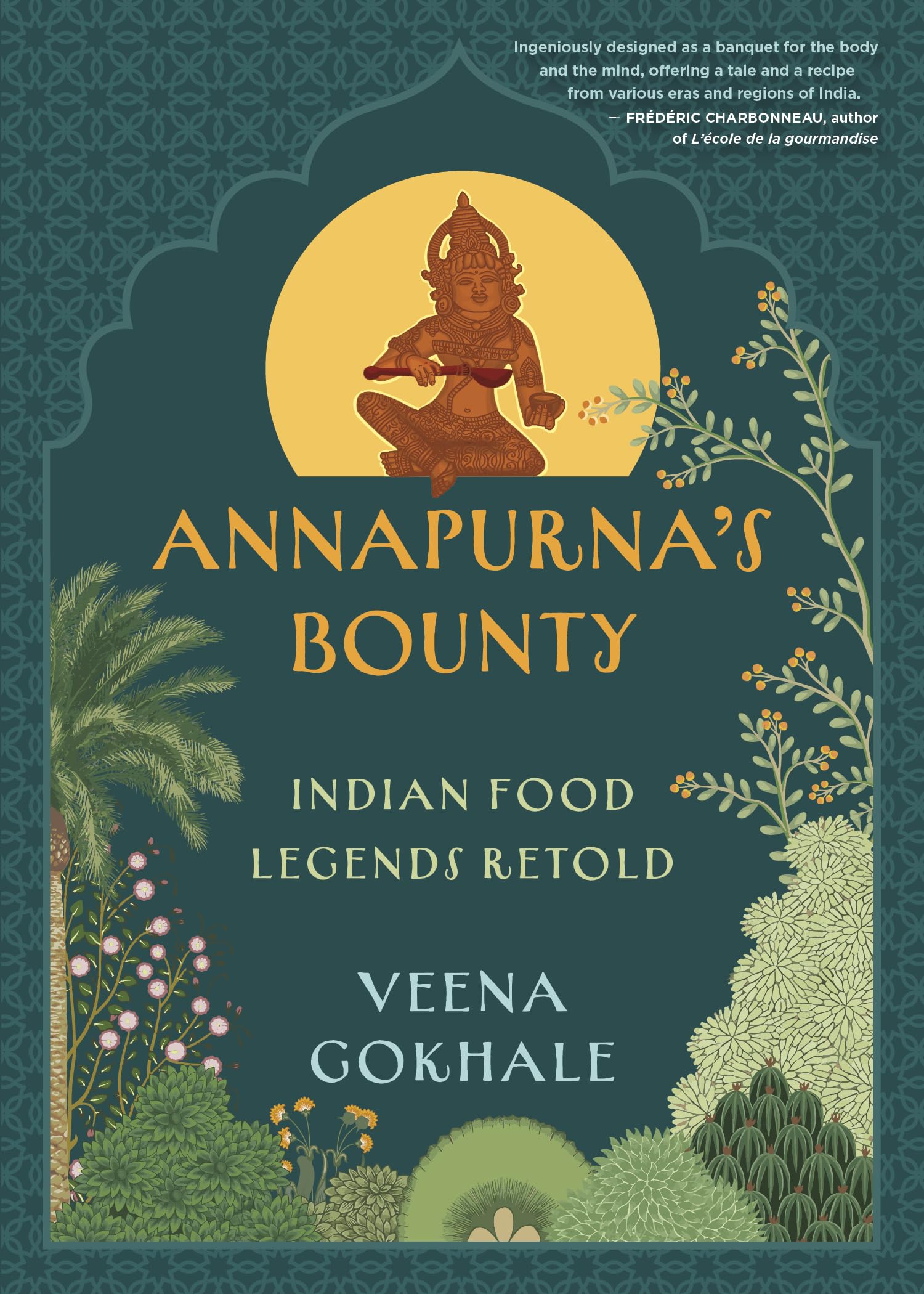

I personally love the title Annapurna, as it is a word I have always associated with nature’s bounty, of abundance, of nurturing and of feeding. It is a concept not necessarily gender-based, and parents are a great example of the idea of annapurna as they nourish the bodies and minds of their children, but one that could apply to any caregiver or guardian who comforts and sustains another.

… engaging stories that have at their hearts a key culinary ingredient or food preparation. At the end of each story is a detailed recipe for the dish the story mentions.

Cooking for someone is an act of love, and the ones who are fortunate to be in such a position are truly blessed. Food is a primary need of all living beings, and the one who facilitates its reach to all in need is most definitely one who should be revered and respected. This concept is central to the book and is the vital component that connects all the protagonists who are rightfully the heroes of the story, the queens, goddesses and even the ordinary mothers that the stories revolve around.

In the very first chapter, “Land of Milk and Sugar” (possibly a play on the words of “land of milk and honey” or the promised land), the author describes in detail how Zoroastrians came to settle in India. The story of these Zoroastrians fleeing religious persecution is well known, as is the legend of their leader adding sugar to a bowl of milk, full to the brim, to demonstrate their intention to co-mingle with their hosts and live amongst them amicably.

This narrative is cleverly interwoven with a fictional tale of a young boy’s personal and extremely perilous journey with his family. His portrayal brings the story to life, and we find out so much about the conditions under which the Zoroastrians completed this journey all the way from Persia to the coastal area of Gujarat. A hearty and traditional stew shared with the family features at the end of the chapter.

Similarly, in the story of “Parvati Bai and the Bandits,” a brave and astute woman feeds a fearsome bandit and his henchmen—who have come to loot and plunder her home—a very special and delectable meal. She wins them over with her grace, tact and hospitality, and they subsequently retreat. The meal itself is described in meticulous detail, each course mouth-watering and exotic in its presentation and wholesomeness. Food attains the status of a powerful bargaining chip in this fable and is used in self-defence.

Food attains the status of a powerful bargaining chip in this fable and is used in self-defence.

On a lighter note, a delightful story about the great Mughal Emperor Akbar, “The Emperor who Loved Mangoes,” not only extols the virtues of this much-loved, delicious fruit but also explains the story behind the idiomatic use of the expression “Birbal’s khichari,” meaning a needlessly slow process, with no hope of completion. The story also gives us a glimpse into the workings of the Mughal court.

In the tragic story “Three Grains of Mustard” is a line that resonates with us all: “In a world where everything changes there is some serenity in accepting the truth that all phenomena are impermanent.” This chapter introduces the reader to the gentle wisdom of Gautama Buddha and demonstrates the universal emotion of grief and the inevitability of mortality as a young mother grapples with loss and questions her own sanity in an unforgiving world.

In the eponymous “Annapurna’s Soup Kitchen,” Gokhale explains how the Goddess Parvati came to be known as Annapurna, the goddess of nature’s bounty.

In the eponymous “Annapurna’s Soup Kitchen,” Gokhale explains how the Goddess Parvati came to be known as Annapurna, the goddess of nature’s bounty. This story is cleverly juxtaposed with that of a young modern family living in the West.

Meanwhile, in the thought-provoking story “Do the Right Thing,” the reader is introduced to the teachings of the founder of Sikhism, Guru Nanak, and the wonderful concept of a langar. A langar, for those who do not know, is a free community kitchen found in Sikh gurdwaras (places of worship) serving freshly prepared vegetarian food to anyone who visits. People are fed irrespective of religion or background. Doing so is a core principle of Sikhism and each langar is run entirely by volunteers and funded by donations.

At the other extreme, the story “Chef William and Captain Tyrant” offers a vivid, painful portrayal of the excesses and ostentatiousness of the British Raj. This story describes an instance where food is not just a means of sustenance but a selfish obsession of the arrogant, for which a person can go to drastic lengths. A very authentic and relevant recipe for Mulligatawny soup features at the end of the chapter.

The final chapter is an affectionate look at the origins of the much-loved and ubiquitous samosa as Sanbusak in Persia.

The final chapter is an affectionate look at the origins of the much-loved and ubiquitous samosa as Sanbusak in Persia, following its travels to Ghazni, on to Lahore and thence to India. Its numerous fillings, from the humble potato to juicy spiced meats, cheeses, nuts and dried fruit, and even sweet coconut, change as the samosa travels, much like the story’s fictional eponymous hero, a hapless ne’er-do-well chancer who somehow fulfils a prophecy of immortality. The artless protagonist faces a rocky and uncertain journey across deserts, royal palaces and the plains next to the river Ganges, alternating between being charming and blundering through life. The story feels not just magical but also fresh, as Gokhale, a consummate storyteller, gives this exciting tale an unexpected and contemporary twist.

This wonderful book would be a great addition to the collection of anyone who has a penchant for simple and nourishing vegetarian Indian food—hearty dals, creamy desserts made with milk and soul-satisfying vegetable stews. Each chapter’s easy-to-follow recipe also explains any unusual ingredients and offers easy substitutes and tweaks, for instance, what one can do to make it a vegan meal. This is an important feature as vegan recipes can sometimes be difficult to source, and Gokhale’s collection offers something for the most diverse of palates.

Most of the recipes are for simple, one-pot meals that feature in the myriad kitchens of the subcontinent with minor regional variations. The khichari, a staple in most of these kitchens, is prepared in a slightly different manner in this book than the one made in Uttar Pradesh where my family comes from. Our khichari is just rice and any type of lentil cooked simply without many spices or turmeric, but garnished with caramelised onions fried in pure ghee and enjoyed with a fiery coriander chutney, yoghurt and pickles. A book such as Annapurna’s Bounty opens up many new and different possibilities, whether new spice mixes—such as the delightful-sounding Goda masala—or incorporating unusual ingredients such as asafoetida and freshly grated coconut into everyday meals.

Just as people travel, so does food.

Just as people travel, so does food. Our palates constantly evolve, perhaps with a tinge of nostalgia for the familiar and traditional food we grew up with but excited nevertheless about new flavours and culinary experiences. The rich tapestry of tastes, aromas and textures of food is woven together over many, many years. The smells, tastes, or even a mere mention of certain foods have the power to magically transport us to moments in our lives that define us.

Each dish or food preparation has its own story to tell. As children, we are told these stories as they are passed down through generations, making them part of our identity. The diversity of the foods and the addition of a plethora of regional delicacies in the book underline this concept beautifully. Food is meant to break down the barriers that humans have created for themselves and to bring people together, not create divisions.

I enjoyed reading this book greatly. As a food writer and a keen and enthusiastic home cook, I have been inspired to try many of the wonderful recipes such as Veena’s karanji, with its exquisite and unusual filling; the Bengali khichari; and the heavenly Persian stew ash reshteh. In some ways, we all carry a bit of Annapurna inside us. Long may it continue.