What does it mean for me to translate fiction from the supposed global peripheries into an imperial language? It is a form of activism. It is to vie for visibility in the one-and-unequal world literary system.

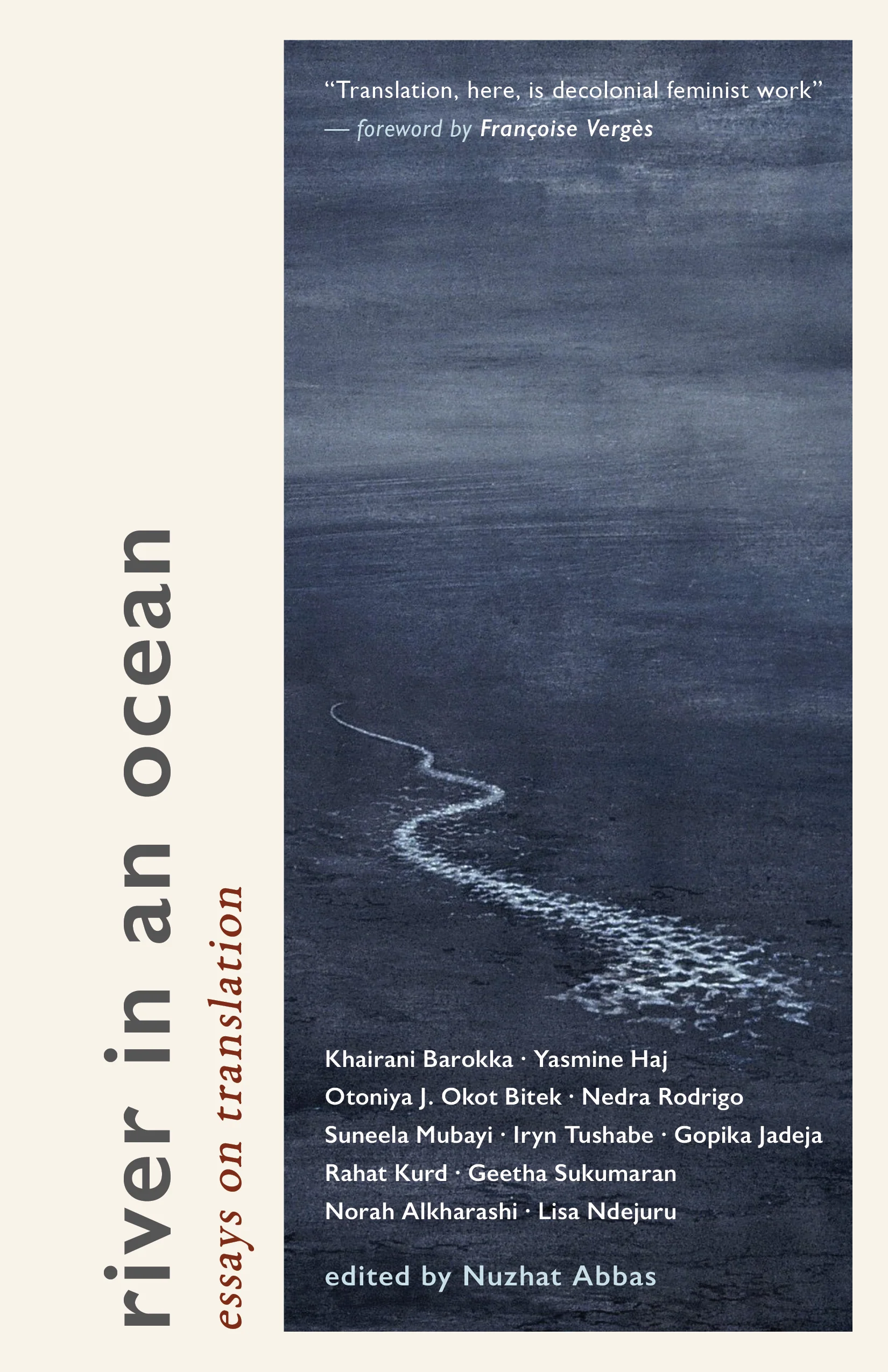

Like me, the contributors to Nuzhat Abbas’ anthology of essays on translation, river in an ocean, navigate a double bind when working with imperial languages. At the heart of our work lies a contradiction: translating anti-imperialist and anti-comprador literature into what Françoise Vergès, in her foreword to this anthology, calls “the language of capitalist globalization.”

I make peace with this choice by saying that I use the borrowed tongue not to impose a singular, uniform culture, but to embrace and acknowledge the richness of global Englishes. After all, why shouldn’t there be a Bangladeshi English?

Why shouldn’t there be a Bangladeshi English?

My question echoes the one raised by Nigerian poet and novelist Gabriel Okara, who compellingly asks, “There are American, West Indian, Australian, Canadian, and New Zealand versions of English… Why shouldn’t there be a Nigerian or West African English which we can use to express our own ideas, thinking, and philosophy in our own way?”

Of course, that’s only one strand in a broader, more complex discussion. The contributors to river in an ocean take up a range of similar questions as they navigate, in Vergès’ words, “the intimacy and otherness of writing [and translating] in English” and other imperial languages.

This multi-authored volume invites “poets, writers and translators” of diverse origins—East African, Middle Eastern, South and Southeast Asian, notably—to explore “decolonial feminism” and reimagine the practice and politics of translation. Editor-publisher Nuzhat Abbas describes the anthology as “an improvised container for critical and creative questions, for contemplation, for decolonial, anti-racist, feminist, queer, and trans dissonance, refusal and rebellion, for care and community.”

This 223-page book is a mehfil, a gathering, of eleven feminist voices from the global majority, each offering a profoundly reflective, structurally innovative, anecdotal essay…

Given these political engagements, you might reasonably wonder whether the book is a theory-heavy read—but it’s the opposite. This 223-page book is a mehfil, a gathering, of eleven feminist voices from the global majority, each offering a profoundly reflective, structurally innovative, anecdotal essay—one that is not exhaustive but meditative, one that will give you the kind of pleasure you get from reading poetry.

These essays invite us to rethink the question of language and landscape in translation, as well as the hegemony of national languages. I am particularly intrigued by Suneela Mubayi’s disillusionment with what she describes as “minor/subaltern” or “embargoed” languages. Mubayi points out that subaltern languages in the national context are also hegemonic and colonial to regional and Indigenous tongues. She cites Bangla, Persian, and Urdu, which may be categorized as “minor” or “subaltern” from a Western perspective, but which function as elite and hegemonic within their own national boundaries.

Any non-Bangla speaker in Bangladesh would likely feel the truth in her words about Bangla’s hegemony. Isn’t that why it’s so rare to find a book in any language other than the dominant one in local bookstores? Bangla towers over the country’s 41 other languages, rendering them almost invisible. But hey, the Anglophone book market in Bangladesh is also thriving, thanks to capitalist globalization!

The essayists in river in an ocean refuse to conform to prescribed literary forms.

The essayists in river in an ocean refuse to conform to prescribed literary forms. Most have embraced innovative structures and experimental techniques.

For example, Khairani Barokka’s opening essay “Apa Kabar, Penerjemah? How Are You, Translator?” swings back and forth between Bahasa Indonesia and its English rendition. It subverts the conventional narrative form, decentres English, and makes me, a reader whose primary access point into the essay is through the English language, hopscotch around the text in compelling, powerful ways. A disabled writer-artist herself, Okka calls out the arts industry’s eugenicist and ableist mentality. She sharply exposes the lack of accessibility for disabled, chronically ill and D/deaf translators, whose material conditions often do not support the well-being of their jiwa raga or soulbodies.

For Yasmine Haj, silence is “an ancient act of translation, musical in essence, magnificent in power.”

Another essay that fascinates me in how it breaks and bends the literary form is “Rast.” In it, Palestinian writer-translator Yasmine Haj compiles a series of worldly-wise, lyrical vignettes that construe quotidian actions, interactions and emotions as musical acts of translation. Haj argues that translation is a sine qua non for survival and provides the analogy of an infant translating its needs through vocal rhythms. Its caregivers then decode, understand and translate its musical articulations. Just as an infant’s premature act of translation is musical, so too is silence. For Haj, silence is “an ancient act of translation, musical in essence, magnificent in power.”

Witty, wise and provocative, Suneela Mubayi, a translator of Kashmiri-Indian and American-Jewish descent, celebrates her interracial and nonbinary identity in “The Temple Whore of Language.” She claims that her liminality makes her a more sensitive translator: “To translate, for me, is to experience being an outsider, a trespasser, a poser—and to be able to revel in that condition.” Always on the move through landscapes and languages such as Arabic, English and Urdu, Mubayi looks at translation not as a mimicry but as a retelling of the original.

Always on the move through landscapes and languages such as Arabic, English and Urdu, Suneela Mubayi looks at translation not as a mimicry but as a retelling of the original.

“Metamorphosis: Journeys, Translations, Writing” by Tamil writer-poet Geetha Sukumaran triggers an epiphany. I realize something excitingly new about how translation—or retelling—is received and responded to in multilingual Indian society.

Mozhipeyarppu, anuvada, tarjome, tarjuma, bhashantara are terms used in different South Asian languages to denote the act of translation. Etymologically, the terms converge on a shared meaning: a retelling of the original. By contrast, the English word translation derives from Latin, meaning “to carry across,” in other words, to carry meaning across languages. This difference in original meanings reveals how the concept of translation is perceived in the two cultural contexts.

Sukumaran’s semantic analysis, supported by G. N. Devy’s research, suggests that historically, translation in India was not mired in anxiety over loss in the process, unlike Western translation theories, which remain caught up in the debate over loss and gain.

What is translation but an act of rewriting, or retelling?

Let me pose a potentially controversial question: What is translation but an act of rewriting, or retelling? A translated text is never a facsimile of the original; it is a new work in its own right. A translator reads a text, interprets it, selects and rejects words to find the most suitable (according to the translator) equivalence within the given context, and then reproduces—or retells—the narrative in another language.

But I digress. Sukumaran’s essay is not just a study of languages; it is also her testament to finding the self and the other in poems and translation. She recalls her childhood foray into deciphering family archives of land deeds. She interprets them as documents carrying a “translation of physical landscapes, borders, heritage, ownership, lineage, and identity.” Her aesthetic sensibility, transnational and translational experience and “postcolonial-settler” identity on Turtle Island bring her closer to understanding “war/trauma poems.” Sukumaran views writing and translation as “political acts that seek solidarity among the oppressed.”

Also aware of her subject position as a “refugee-settler” on Indigenous lands, Nedra Rodrigo wrestles and reconciles with her presence here in North America and her past there in war-torn Sri Lanka in “Crossing Terrains: Unsettling Tinai while Translating Tamil.” Rodrigo not only contends with her transnational identity but also mourns the ecological and cultural losses of war. Lamenting the destruction of trees in war-ravaged Sri Lanka, she writes: “I think of destroyed palmyrah groves and wonder how a tree can become the target of contradicting identities.” Her lament strikes a chord with me, given my Bangladeshi roots and the haunting postmemory of our 1971 independence struggle.

My mind crawls back to an article by Syeda Fatema Rahman analyzing a specific moment in Life and Political Reality, a novella I co-translated in 2022. Life recounts Bangladesh’s liberation war, including a brief but telling episode in which plant life is destroyed. Rahman focuses on this moment to explore how trees on occupied land become military targets in times of conflict. She draws a powerful parallel between the destruction of olive trees by Israeli forces in present-day Palestine and the uprooting of tulsi and hibiscus plants—dismissed as “Hindu plants”—by pro-Islamist collaborators in Life.

Reflecting on these resonances, I, like Rodrigo, find myself wondering how plants, too, get tangled in questions of identity, religion and resistance.

Rahat Kurd’s intimate writings in river in an ocean also comment on cultural genocide.

Rahat Kurd’s intimate writings in river in an ocean also comment on cultural genocide. Her “Elegiac Moods—Letters to Agha Shahid Ali” is one of two epistolary essays in the collection. Kurd composes seven letters to the late Kashmiri American poet Agha Shahid Ali. Her letters reference the removal of Dal Lake’s heritage lights and decry the Indian state’s destruction of a built environment that was historically significant to Kashmiris. She marks it as a direct assault on public memory and seeks refuge in Kashmiri poetry and songs that still sustain a “centuries-old cultural continuum.”

In “The Meaning of a Song,” Kenyan-born, Ugandan-raised Otoniya J. Okot Bitek pens a sequence of unsent letters addressed to her late poet-father, Okot p’Bitek. Pictures from the family archives add a personal touch to her poetic prose. Through these letters, Okot Bitek interrogates patriarchal norms and stakes her claim to poetry as the daughter of a Ugandan exile poet whose legacy is “jealously guarded.” In her essay, walking becomes storytelling. As she wanders through places in the UK where her father tread as a graduate student in the 1950s and 60s, she becomes an itinerant storyteller who weaves spatial stories from social, political and personal memories.

Iryn Tushabe turns our attention from Okot Bitek’s northern Ugandan Acholi language to Tushabe’s own Western Ugandan Rukiga language. “Saved” speaks movingly about the ways that Western evangelicals spread their tentacles of power across Uganda, damaging Ugandan languages and influencing their legislation. A case in point is the “Kill the Gays Bill” of 2009.

Gopika Jadeja looks into the fraught issue of translating Dalit and Adivasi poetry from Western India, as a Hindu upper-caste woman.

For me, what is most rewarding about reading the essays is that they apprise me of my situatedness as a translator belonging to the dominant culture in my country, translating literature from national and global margins into the globally dominant language, English. Gopika Jadeja asks if we can call such a person a decolonial translator. Her inquiry rings in my ears as I write this. In “A Tally of Unfulfilled Longings: Translating Dalit Poetry,” Jadeja looks into the fraught issue of translating Dalit and Adivasi poetry from Western India, as a Hindu upper-caste woman.

I am now translating a Bangla short story about a Santal man who presses his merchant client about making overdue payments for the monitor lizard skins he and his forefathers sold to the merchant class. As the Santal man speaks, he skins a monitor lizard and leaves it to wriggle about and crawl across the floor. This story about an Indigenous man who speaks pidgin Bangla to communicate with his Bengali upper-caste client puts me in a tight spot. In addition, the story is written by a man who is part of the Bengali majority in Bangladesh, and I am making the characters interact in English. I am on a slippery slope!

So, when Khairani Barokka asks if we must make everything comprehensible to the English-speaking world, I shift uncomfortably in my chair. “… Indigenous communities,” she writes, “are facing life or death situations in which communal knowledge needs to be protected from outside capture, including via a translation into languages such as English.”

Lisa Ndejuru’s attempt to re-translate stories from precolonial Rwanda roughly stems from a similar urge to liberate ibitekerezo/wisdom stories from colonial capture.

Lisa Ndejuru’s attempt to re-translate stories from precolonial Rwanda roughly stems from a similar urge to liberate ibitekerezo/wisdom stories from colonial capture. “And the Heart Became Child” lays out Ndejuru’s collaborative project of “waking” Rwandan myth and history, to build an archive “unspoiled by the history of colonialism and organized religion,” to revive stories “grounded in the land—in rivers and lakes and volcanoes—in trees and in animals.”

Finally, “Translating Courageously.” Norah Alkharashi’s essay title captures the ethos of her fellow contributors. As a Saudi Arabian-born and Canadian immigrant poet-translator, Alkharashi approaches translation with deep sensitivity and thoughtfulness, particularly when translating the writings of an author who, like her, is also an immigrant. Care, caution and discretion are her guiding principles in rendering the Haitian-American author Edwidge Danticat into Arabic. She observes that sharing an immigrant background does not necessarily mean sharing the same voice or perspective.

In choosing to translate Black Caribbean stories into Arabic, a language that often essentializes Blackness, Alkharashi aims to revolt against structured silences, counter anti-Blackness and forge “a shared decolonial future.”

In choosing to translate Black Caribbean stories into Arabic, a language that often essentializes Blackness, Alkharashi aims to revolt against structured silences, counter anti-Blackness and forge “a shared decolonial future.” In a male-dominated literary space where women are spoken for/about, she steps up to “traffic in words and literature.”

All in all, river in an ocean serves as a handbook for writers and translators attuned to decolonial approaches, offering a vivid tapestry of personal, poignant and often sharp-witted reflections on life, resistance and activism. Reading these creative nonfiction pieces was at times revelatory and at other times deeply affirming. I found myself nodding, even wanting to say aloud, “Yes, I feel that, too.”

There is something melancholy about finishing a book. When you turn that last page, you see the world you inhabited for a while slipping away. I remember the first time I boarded a flight to Canada. I knew what crossing the threshold at the airport gate meant: the end of the old ways of life, love, friendships.

Surely, closing this book will evoke a similar sense of loss and estrangement, but you will find yourself crawling back to it for comfort, wisdom and delight. This one, here, is not for reading in one sitting. You are not meant to gulp it down in one bite but to savour it. Reading it a second or even a third time is a more gratifying, intellectually stimulating experience.

More on t r a c e – a valiant not-for-profit press that we invite you to support

“t r a c e publishes books that illuminate, in complex, beautiful and thought-provoking ways, contemporary and historical experiences of conflict, war, displacement, exile, migration, life, labour, love and resistance.

At a time of unprecedented global change, t r a c e invites writers and readers to build community and solidarity through small books and events.” (t r a c e)