[First published in A. Rivista anarchica, anno 40, n.2 (352) aprile 2010, pp. 47-49, Milano, Italia. Translation by Maya Khankhoje]

Imperialism is a phenomenon which dates back all the way to antiquity, its epicenter having changed throughout the centuries. When conditions have permitted it, it has matured in the West, with England standing out amongst the most rapacious nations, which, before becoming a model of democracy (a notion which is contested by many) had gone through long periods of expansionism. The so-called Commonwealth is nothing else but the heir of old colonialism.

India was one of the largest and oldest nations to free itself from the tutelage of the British lion and its independence was hailed by the United Nations Organization in 1947. But in fact, the prevailing Mountbatten plan did not satisfy Gandhi whose misgivings were confirmed by the events that followed: the Indo-Pakistan war and the assassination of the Mahatma.

Today, in spite of its instability, the country is slowly transforming itself into a modern democracy even though it is still torn by religious, political and linguistic intestinal wars.

India has been the scenario of many violent confrontations of a repressive and irredentist nature and the struggle of its people against internal and external oppressors is full of episodes. Revolutionaries have devised new methods of revolt and, for the first time in history, a very large collectivity has been able to avoid subservience to foreign powers by adopting original mechanisms that date back to the nineteenth century and which find their roots in non-violence. Gandhi, the guru, was inspired directly by the christian anarchism of Tolstoy, who in turn was influenced by Proudhon, a libertarian federalist.

Be it as it may, if the Indian people embraced the non-violent solution, it happened after a long journey of hesitations and not before having practiced other forms of struggle. Independence-seeking intellectuals experienced this slow evolutionary process and wound up either resigning themselves to it or enthusiastically adhering to the “Gandhian method.” Amongst these we have the fine example of Pandurang Khankhoje who typifies the conversion of the Indian people to the precepts of the Mahatma.

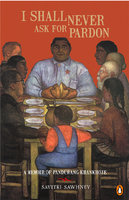

The recent publication of I Shall Never Ask for Pardon: A Memoir of Pandurang Khankhoje (Penguin Books India, 2008) edited by Savitri Sawhney, daughter of the author who passed away long ago in 1967, is noteworthy. During my only trip to India, in 1987, I had the honour of being received by the Khankhoje family and had the pleasure of meeting his widow (now deceased herself), his daughter Savitri (sister of my dear friend Maya who resides in Canada) and her husband and daughter. At that time this book was just a vague project. After twenty years I am pleased to see that it has been realized and authored by one of the daughters (both of them with a skilled pen). In order to avoid falling into panegyric, Sawhney has availed herself of the hand-written memoirs of her father, her family as well as official archives, ample collected correspondence, newspaper cuttings, testimony by third parties, personal reminiscences. In sum, it is a rich combination of elements that rely on news, direct observation, always supported by objective confirmation, primary and secondary sources, wisely interwoven. A vibrant portrait of humanity and wisdom becomes evident.

The recent publication of I Shall Never Ask for Pardon: A Memoir of Pandurang Khankhoje (Penguin Books India, 2008) edited by Savitri Sawhney, daughter of the author who passed away long ago in 1967, is noteworthy. During my only trip to India, in 1987, I had the honour of being received by the Khankhoje family and had the pleasure of meeting his widow (now deceased herself), his daughter Savitri (sister of my dear friend Maya who resides in Canada) and her husband and daughter. At that time this book was just a vague project. After twenty years I am pleased to see that it has been realized and authored by one of the daughters (both of them with a skilled pen). In order to avoid falling into panegyric, Sawhney has availed herself of the hand-written memoirs of her father, her family as well as official archives, ample collected correspondence, newspaper cuttings, testimony by third parties, personal reminiscences. In sum, it is a rich combination of elements that rely on news, direct observation, always supported by objective confirmation, primary and secondary sources, wisely interwoven. A vibrant portrait of humanity and wisdom becomes evident.

The life of Khankhoje is rich in unusual events. Just to begin with, journeys that take him from India to Indochina, then to Hong Kong and Japan, the United States. Then again Asia, Afghanistan, Persia, Tashkent, then Mexico (where he gets married and where his two daughters are born). During these shifts and long stays in various countries, he learns many languages and even acquires scientific knowledge graduating in agronomy (a field in which he would become a great specialist). He meets outstanding personalities: Sun-Yat-Sen (to whom he would teach English), Lenin (who held him in high esteem), Pandit Nehru (who hailed him as a freedom fighter), Diego Rivera (who would paint him in a fresco and would become his close friend), Rajendra Prasad (to whom he would write a report on the agricultural problems of India), Tina Modotti (exiled Italian political figure who would become a great photographer in Mexico) and so on. He frequents Indian anarchists in exile, amongst whom is the well known M.P.T. Acharya (later editor of Indian Libertarian of Bombay) and the very active Har Dayal (expelled from the United States for his anarchist militancy) as well as American and Mexican comrades amongst whom stand out the Ricardo and Enrique Flores Magón brothers, as well as William C. Owen, editor of the English page of Regeneración, sympathizing with the Mexican revolutionary cause which, by the way, was very similar to the Indian one. Pandurang Khankhoje even joined the Industrial Workers of the World who found him work as a lumberjack in Astoria, while he studied at Corvallis, in Oregon State University. Pandurang Khankhoje, even though he appreciated the anarchist point of view and sympathized a lot with the ideas of the Magón brothers, and above all, with those of Har Dayal — who became his right-hand man within the Ghadar party (founded by them in California and Portland in May 1913) –would not fully join the anarchist movement, just as he would not join the Communist Party even after 1917 and in spite of his enthusiasm for the Russian Revolution and for Lenin.

Ever since he was young Pandurang decided to devote his life to achieving India’s independence. He plunged into politics very early on and at the age of ten already founded a secret society: Bal Samaj which then became Bandhav Samaj. He created cells with four members who swore to fight for independence. It is a question, of course, of armed struggle, because this precedes the Gandhian period. When his father chose a bride for him (as was then the tradition in Indian society) he refused with the pretext of wanting to offer his life to the imminent revolution. His father was indignant but shortly afterwards he tried again so his son was obliged to run away from home, turning down the money for expenses that his mother offered him. However, he did accept some sweets that she made for him just before leaving, with the warning to only eat them when suffering great penury or dearth. When the time arrived to resort to those snacks, Pandurang realized that each one contained a gold coin. It sounds like a fable from other times…

His journey would last decades during which he would not stop fighting for the independence of his country by any means. Side by side with his agricultural studies he would also develop a military career convinced that the handling of weapons was essential to achieve victory. In America he was able to register at the Mount Tamalpais Military Academy. During his student days he was active and founded in Berkley the league for Indian Independence. British authorities were keeping watch over him intercepting his correspondence (straightaway arresting the addressees of his letters). The Portland chapter of that League was very active and had 400 members. Pandurang envisaged disembarking with a thousand volunteers in a neighbouring country and from there initiating armed struggle with a cross-border invasion, but the British counterespionage services were well organized, thwarting all attempts at revolt by means of intrigue, preventive arrests, systematic repression. In order to increase membership, Khankhoje became associated with Sikhs. To be able to communicate with other revolutionary and freedom fighting factions he learned other Indian languages. His mother tongue was Marathi (in which he wrote his memoirs), but he started studying Punjabi and Urdu while he had a smattering of Afghani and Farsi, a bit of Chinese and Japanese, to which he later on added Spanish and French. But by then he had a high-profile and could not go about incognito under any circumstances even if he changed his address to hide. He was fighting powerful and astute enemies and all his movements were under surveillance, noted, foiled. He finally realized this and wound up embracing the Gandhian solution, the opposite of his own. The Mahatma faced his enemy head on. One must remember that every time Gandhi organized a protest demonstration he advised the British authorities. He would not ask for permission, he merely informed the enemy of his intentions. Passive resistance was not for everybody, it requires a tremendous inner discipline, but when it is practiced seriously, systematically and stoically, it may end up in unexpected results.

Khankhoje took to heart his extraordinary and, perhaps even contradictory experiences: the violent revolution in Mexico in 1910 and the non-violent one in India about thirty years later. Too wise to settle for provisional and incomplete results he was able to foresee the drawbacks of both that might ensue from a merely political victory. It was necessary to intervene at an economic and social level. The conquest of power or the instauration of parliamentary democracy picked up morale but did not, in and of themselves, solve the practical problem of survival. It is no coincidence that he completed agricultural studies and wanted to put them to good use. Rivera precisely painted him in his fresco surrounded by ears of corn. We can imagine Khankhoje followed in the work started by my acquaintance and fellow citizen Prof. Mario Calvino (father of Italo, the writer) who had understood that Mexico should develop its agriculture, be it to feed the population, be it to lead it in the right path towards self sufficiency and economic independence. They did not listen to Calvino so he went off to Cuba and Khankhoje would face the same situation decades later. Having returned to India in the fifties he would in fact try to apply his Mexican discoveries to local conditions but his efforts would be hindered by bureaucrats and politicians.

Pandurang reacquired his lost citizenship but he had by then reached retirement age, so he turned to writing his memoirs, proud of having left traces of his work in Mexico and in India and proud even of having brought the two countries closer to each other politically. Mexico was, in fact, the first country to recognize the sovereignty of India, henceforth independent from British domination. He died in 1967 at the age of 81, leaving behind, like a true internationalist, a European wife (Jeanne Khankhoje was Belgian), an Indian daughter (Savitri) and a Mexican daughter (Maya). His heart and his mind, on the other hand, did not belong to any country, but rather to humanity.