Brique par Brique’s mission is to bring together diverse people in all their complexity and beauty and build housing to nurture community, support free expression and inspire positive change. Staff and members have been creatively realizing their vision, brick by brick, since 2016, in Montréal’s Park Extension neighbourhood. In August, Montréal Serai editors Jessica Stilwell and Jody Freeman sat down with Faiz Abhuani, the organization’s founder and current director, to talk grassroots infrastructure, economic privilege, the complexities of the housing sector and the ways Brique par Brique brings together community life and community living. This interview has been edited for publication.

Jessica: Firstly, we’d love to hear about your particular Brick by Brick story. Were you there from the beginning? How have you been involved, and how has that evolved over time?

Faiz: It’s a difficult question to answer, because there are so many different ways to tell the story and so many different stories. But I guess I can say that in many respects I am the founder, or I’m recognized to be the founder, although I never really did much alone. The only thing I did alone was sell [real estate]. But everything else, the concept and problems and the people, was something I did with the help of a lot of people.

The founding group was an art collective that doesn’t exist anymore. It included Sophie Le-Phat Ho, who is now a fashion designer and facilitator at Coco. They specialize in facilitation and organizational services for community organizations, and focus on Anglophone organizations in Montréal. And there was also my buddy Kevin Yuen Kit Lo, who is a designer by trade. He was the activist. Now he teaches design at Concordia University. And together with a few other people, we were part of a group called Artivistic (a name that’s aged very badly), which melded the disciplines of academia, activism and art to intervene around various issues that we felt were under-discussed or underappreciated or undervalued.

We would organize these festivals and we participated in the politics of the time. This was during the Bouchard-Taylor Commission on Reasonable Accommodation [in 2007], so it was a lot about that. There was a lot of anti-racist work, and explorations of what was to be later known as identity politics, which now is like a bad word, because it denies the identities of the people involved. But this was before the words BIPOC and all that stuff were mainstream…Before EDI [Equity, Diversity, Inclusion]. Before all that jazz.

We were inviting people from all over the world to come and just have a conversation about stuff and keep the discourse evolving. That was also before video conferencing. So we had to fly people over. And on one occasion in 2009, we had a festival which centred around the topic of sexuality. We had spent all of our grant money on flying people in, because we were really excited about getting as many cool people as possible to talk and share what they were doing.

We were like, well, we’re going to organize ourselves.

We didn’t really have any money to feed people or house people, so I came up with this concept of infrastructure crews. Instead of just doing the nonprofit industrial complex thing where you ask for grants and then you pay for stuff, we were like, well, we’re going to organize ourselves. It was very much inspired by anarchist mutual aid principles. The idea of getting people organized to take care of themselves was something that became central to my thinking… And when I got out of activism and art and got into really building community projects, I worked with Sophie. We were both living in Park Ex at the time.

To talk about the sort of philosophical genealogy of this organization that’s Brick by Brick: one part is what came out of Artivistic and trying to organize around issues from these three perspectives. And the other piece came from something [that] came up for me at the Anarchist Bookfair in the early 2010s. I realized that a lot of the people who were at the book fair, despite being dressed like punks and looking like bums, had actually flown in from all over … [It got me thinking] about how there still was such a revolving door or turnover in the activist world, with social centres opening up and closing, and people moving into town, joining groups and moving out of town.

I realized that I had forgotten about class. And a lot of the people who are involved in organizing actually came from privilege. They were not organizing from a position of systemic exclusion, the way that I had been organizing. And I had to start becoming honest about why I organized. Was it because I saw so much tragedy and avoidable harm and wanted to do something about it? Or that I had something to prove, because for sociological reasons and also for very personal reasons related to my own journey, I wanted to externalize some of the pain that I had experienced?

I realized that everybody else is coming from a different place—and a lot of people at the Book Fair and in organizing actually have quite a bit of privilege. They come from family wealth and they’re going to have to face the problem of their own privilege eventually … And after doing some research, I realized that there were already solutions for these people. [There] was a small, growing industry called responsible investing, impact investing and all that kind of stuff.

I learned that there was going to be a massive generational wealth transfer—from people who “earned” their money in a much more favourable environment economically, to people who are the first generation in a very long time to be better educated than their parents, but have [fewer] opportunities and are going to inherit a whole bunch of resources that they didn’t earn. So their whole decision-making around what to do with that is going to be very different.

I felt like we should pool resources and build our own organizations and take care of ourselves, build infrastructure for social change, because at the time I had started working in the community sector. I was working at Project Genesis, an organization providing all kinds of social services. But upstairs, there were the community organizers. They were much fewer than the lawyers and social workers working downstairs, but they looked at the data from the community, from the service providers, and organized around the issues.

I felt like there was no room to do things that were experimental and interesting and, at the end of the day, revolutionary, and that the community sector was essentially there to just patch up things for the government.

My specialty—my angle—was access to health care, because immigrant populations in Quebec, in systemic ways, through all kinds of different administrative hurdles, didn’t have access to some basic medical services. This was causing a lot of problems: people not going to the doctor because they didn’t want to incur a debt; people having massive debt after giving birth, or whatever. I felt like the agenda was being set around the needs of the funders… I felt like there was no room to do things that were experimental and interesting and, at the end of the day, revolutionary, and that the community sector was essentially there to just patch up things for the government.

So I was like: We need to organize our own. We need to build our own organizations that are self-sustaining, that are not dependent on foundations and government for their funding. In talking to some people, consultants, fancy people on the Left, I learned that you can’t really just ask people to pool their resources and then play with their money as you wish. If you want to pool resources—like real investment money, far beyond the scale of just fundraising—then you need to offer your investors some degree of security.

Given that we were entering a housing crisis in Park Ex, I felt like the best way to intervene was through housing, and I was an anti-gentrification activist. For me it was natural [to focus on] housing, social housing. Gentrification is so intersectional—it really hits neighbourhoods like immigrant neighbourhoods. It [involves dealing] with racism very directly, because the landlords are very explicitly racist. It [comes with] a lot gender issues and norms. And the direct impact on the ability of women to be free from their partners depends a lot on whether they can find a home elsewhere. The success rate of kids in a school greatly depends on whether they have stable housing or keep having to move, like I did. That really has a huge impact on their confidence, on their ability to succeed and on their sense of belonging.

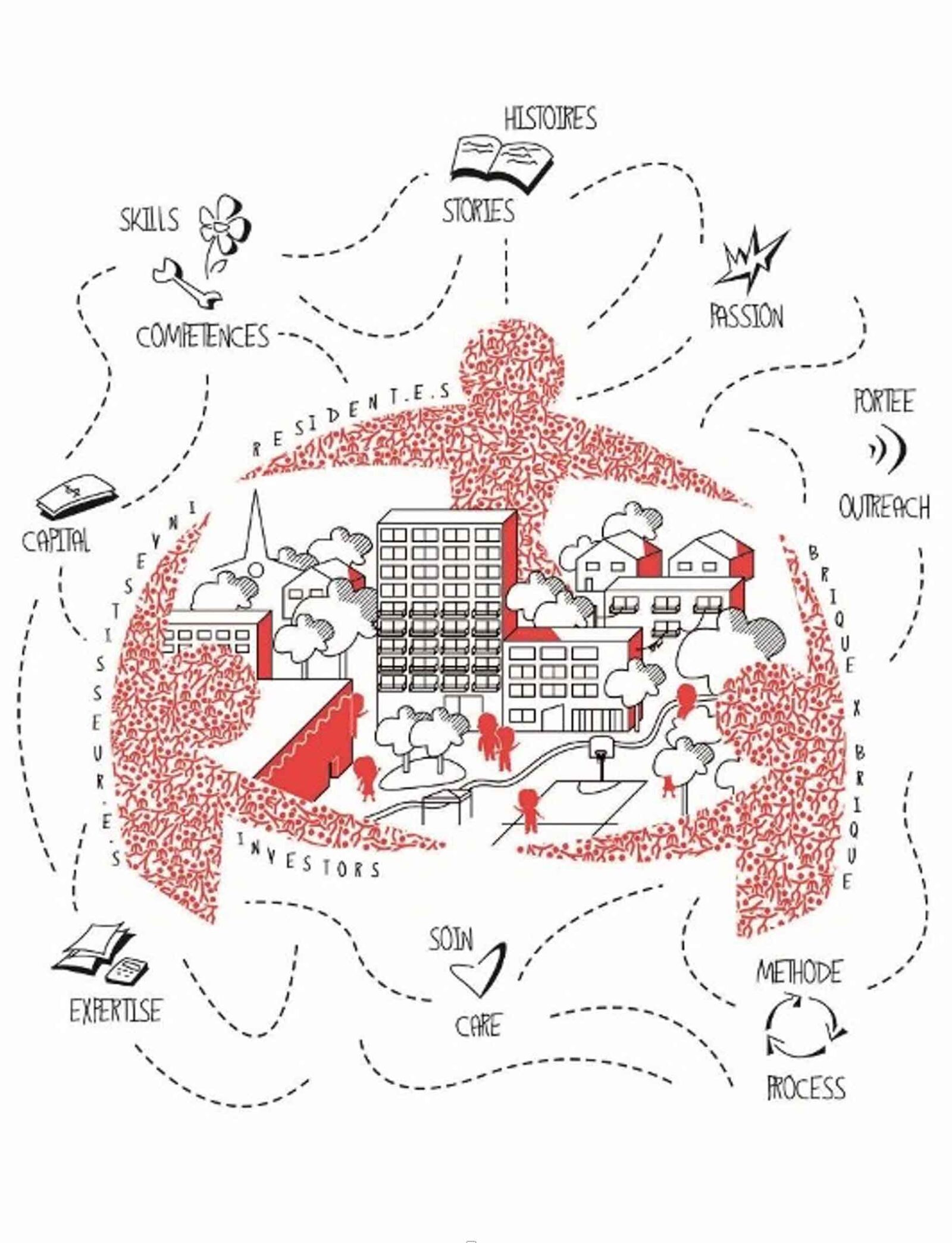

I’m going into a great deal of detail here just to show you that we [Brick by Brick] were never about housing per se. We were really about building solidarity between people who are directly affected by capitalism and colonialism, and people who are affected in a different, more existential way—and to build a strong link between the two groups. It’s not just two [groups], it’s a whole spectrum.

Is [housing] a fundamental human right? It has a very basic use value: it’s shelter. We felt like [our approach to housing] would be the best way to centre community organizing, community building. Experimenting, incubating and playing with the possibility of a different kind of world through the communities that we would build around these housing projects—we saw that as a crazy dream. It hasn’t really succeeded at the scale that I would like, or at least not as quickly as I would like. But that’s fine. We’re getting there… growth is not linear.

Jessica: Could you talk to us a little bit about the current relationship between this push for housing and the cultural and artistic activities that Brick by Brick is also doing? What does it look like today to have those two [spheres] together?

Faiz: There are two kinds of organizations that do housing in the community sector. One is grassroots or community organizations that are rooted in a specific community or want to serve a specific population. It might be a community group that serves a low-income neighbourhood, or women who need shelters… Or a community that serves a particular ethnic group [wanting] to build services for their people. Religious organizations get into this kind of thing. They identify a site and then lobby the government. They get foundations to help them a little bit, but because it’s so capital intensive, you really need government intervention.

The other category is non-profits that specialize in actually building social and affordable housing projects. They tend to be technocratic—a path for people who want meaningful work but are driven more by the job than by the impact of their work. If they’re good, they end up working for the city, where the pay is better, or for a private developer.

We’re a community group, but we’re also a group that wants to build housing. We’re not looking to compete against other organizations. We’re looking to contribute to a social change project.

In Quebec 5%, and in Canada 3% of all real estate development projects are social purpose projects. There are countries in Europe where it’s in the 20s and 30s [percent range]. There are countries in Asia where, like in Singapore, 90% of all real estate is state-sponsored or state-owned. So, the potential for democratic input on who gets access and at what price is much greater in those countries than in Canada. … And then the granting agencies? Their requirements are so over-the-top. In the private sector it’s not complicated. You take the risk. You come up with the money, you build the project. We straddle the public sector and the private sector.

Generally speaking, people are willing to invest 10 to 20 times more money than they’re willing to give.

How does Brick by Brick do stuff privately? Pooling resources. We issued community bonds, which are the only way outside of a bank loan that a nonprofit can raise money from the general public, as in raise investment capital. And why investments? Why not donations? Because, generally speaking, people are willing to invest 10 to 20 times more money than they’re willing to give. That’s really reflected in the charitable sector: foundations give 5% of their endowments every year, and they invest 95%. I think we’re the only [housing-focused community group in Quebec] that raises money in the private sector. We’re different because we want to build more housing, not because we identify as a housing group.

Community organizing allows Brick by Brick to bring people together in our communities that are undervalued and to support them in better expressing themselves and valuing their own culture. We document that work and produce content that’s accessible to the average Canadian. By communicating that we’re real, that we’re connected to people, that we’re not service providers, that what we do is empower people, we show that our housing projects would have a great deal of value, not just for the individual person who accesses the housing, but for their families, their communities and their neighborhoods.

Jessica: Can I ask you to project forward into the future? What is the big dream that’s keeping you motivated through all of this complexity and trying to explain to people why they should care about it?

Faiz: I never really set out to do housing. And it makes sense in Canada; it’s cold, and everything is owned. There’s no commons. If you don’t live in one place, you have to live in another place. So, access to housing is intertwined with stability and safety. And, in that sense, I’m very personally affected by it. I moved 30 times in 40 years. Thankfully, things have changed for me; I now own my home. I’ve really changed class. My parents were refugees from Eastern Africa. They were stuck between different people, and they were foreigners. Even though it was their home; they’d been there for generations. They were considered to be foreign — and they’re not faultless, they were by no means radicals. They really wanted to protect their own community, and that was the most important thing for them, and that was a good thing, because it allowed them to survive. And it was a horrible thing, because they lost their humanity in that process. Their grandparents were in India [during Partition]. They were Muslims [during] the largest human migration in history. It was a mess, and I felt like there was something inside of me that was like, we’ve been moving for generations, and I’m still moving, and not just moving. I’m being shuffled around and I’m sick of it.

But that being said, it’s not about me, […and] the organization is more than just me. The organization is a bunch of people who all have different experiences and who recognize that what brings us together is how we are all differently affected by capitalism … and colonialism. The real objective is not a Park Ex thing, or a Québec thing, or a Montréal thing or a Canadian thing. The objective is to build infrastructure that’s going to bring people together from around the world in a future that is very, very difficult to predict, but will certainly be one where the opportunities are not set by any kind of material boundaries. They’re [being] set by political boundaries. And those political boundaries need to be understood. We are going on our path, which is infrastructure, housing, finance, community organizing. That’s where we want to go.

Jessica: It’s wonderful to hear this point that tends to be so abstract in a lot of activist spaces, be brought into the very concrete reality of four walls and a roof. This feels profoundly hopeful to me, even as you’re saying the scalability is a problem.

Jody: How is it going with the Plaza Hutchison and 8600 de l’Épée?

Faiz: The 8600 is done, like all the back-end stuff is done. The demolition work is coming up in February, and the foundation is going to get poured before in the spring; and then the structure, which is a very simple, cheap wood brick, in the summer. This time next year, we’ll be moving folks in. Plaza Hutchison has the potential of being much more interesting, but unfortunately the main problem in everything that we’ve done so far is one or another layer of government.

Hutchison Plaza is a great example of this. Since 2012, the city has been increasing its budget enormously, because real estate prices have gone up and the city’s budget comes from land taxes. When this progressive government came into power for the first time, Projet Montréal, their only social strategy really was social housing. Everything else was about transportation, the green transition, all that kind of stuff which is really just another word for gentrification. A lot of the people in the administration really can’t tell the difference between making the city more attractive to middle-class families and the green transition, so their focus is not really on hitting actual emissions reduction. It’s really just about making the city less oppressive for people who want more space, less noise, fewer annoyances, fewer poor people, less insecurity.

They wanted to build a lot of social housing. So they bought up a whole lot of land. But they didn’t really have a strategy for developing these sites. Decades earlier, the city [had] divested enormously, [including] from the most beautiful spot in Park Ex, from a historical standpoint, the train station, some 20 years ago, [by selling] to Loblaws. One part of the deal that the city sold was, some of the space had to be given to community groups. That never happened. After many years of divesting, the city [then] bought a bunch of land. They bought the Plaza Hutchison and, many years later, it’s still empty, and its condition is getting worse and worse.

Jody: Brick by Brick seems to be quite successful at bringing in members and having active members. Are some of those members involved in investing?

Faiz: The members are behind us a hundred percent. It’s a small enough organization that the relationship is one of trust, almost family-like. Recently, we had a conflict. We had a meeting because I was going to buy the old Laurentian Bank on the corner of Jean Talon and De l’Épée [… but it] didn’t work out, and we were a bit sad. I proposed some other opportunities outside of the neighbourhood, and [my coworker] Masoon (Balouch) was very sad because her group is largely made up of asylum-seeking women in Park Ex, and she doesn’t want to leave the neighbourhood. [But] this is not about moving. This is about meeting the needs of a larger group and scaling, and different people are involved for different reasons. [For some,] this is a South Asian progressive hub, a place to reconnect with their ancestors. For [others], this is a place to help people, or to be creative, or to work on housing. Ultimately, I was able to hear Masoon and we made up, not the least because of her ability to balance an open mind with strong convictions. I see now that expansion and rootedness are not mutually exclusive.

Jessica: If any of the people reading this interview are interested in partnering in some way, or getting involved in some way with Brick by Brick, what would be your recommendation to them?

Faiz: For partnerships, people can email me personally at faiz@briqueparbrique.com. To be engaged as a volunteer, as a collaborator, as someone who does programming at the centre, or to get on our housing list, or whatever, that’s mostly through our WhatsApp channels, just to our website and follow the links! Brick by Brick is looking for all kinds of expertise. If you’re a professional, lawyer, engineer, whatever, please write to us.

To get involved with what Brique par Brique is doing in Parc Extension and beyond, email info@briqueparbrique.com, or check out the many ways to learn more and do more on their Linktree.

Follow them on Facebook @briqueparbrique and Instagram @briquexbrique.