I am a river running through ancient lands,

Like veins carrying ancestral memories,

A thousand stories whisper on winds,

And land like drumbeats upon our hearts.

— Dan David*

Every now and then, a wisp of memory invades that foggy space between sleep and waking in the middle of the night. Not every night, but often enough to pull my thoughts back to a time in my childhood. I sit up and try to remember.

I must have been four years old. We lived just downhill from Syracuse University in a row of military veterans’ housing built fast and cheap after the Second World War. Former military raised their growing families in this temporary neighbourhood. After our family moved north to Canada, it was torn down to make way for middle-class homes with large lawns.

I remember the move and the cramped sleeping area in the attic above my grandparents’ home at Kanehsatà:ke (formerly the Oka Reserve) — the arguments about hogging blankets, growls from grownups downstairs to shut up and get to sleep or else… my older brother taunting me about my girlfriends, my two Black girlfriends, left behind in Syracuse.

Way back then, I’d toddle over to their place just doors away, to play with them. I have no other memory than that. One of their names — a nickname, so I’m told — was Pumpkin. Hardly girlfriends at three or four years old, except that they were girls who I considered friends. But the description that they were “Black” (or words to that effect) wounded me. I couldn’t understand why.

Hardly girlfriends at three or four years old, except that they were girls who I considered friends. But the description that they were “Black” (or words to that effect) wounded me. I couldn’t understand why.

By the time I was seven or eight, that description was seared into my young brain, a scar that never really healed. The words frame questions that haunt me decades later. I have no real memory of those two young girls, and that makes me confused, proud and somehow ashamed all at once.

Much later, sometime in my late teens, I tried to parse the words to understand my mixed emotions. I had friends who were girls, and as a young boy this generated certain confused feelings, all perfectly normal at that age. It was part of growing up. But why would the fact that they were “Black” generate both pride and shame?

My parents must have known where I was when I wandered off to visit my “girlfriends” a few doors down. They must have decided I was safe, in good hands with the girls’ parents. Race didn’t seem to matter to my parents, so why should I feel uneasy at my brother’s taunt? Wasn’t my friendship with the girls a good thing?

Actually, it was good… but the taunt still stung my younger self because the words were steeped in the constant barrage of prejudices of the time that were all-pervasive — in the schoolyard, on the bus, on TV and on the radio, in movies and newspapers. Everywhere. If it wasn’t about the “other” then it was about “me,” my growing sense of my Mohawk self and the shame society infused into my identity.

Thankfully, there were other messages that challenged society’s malignant beliefs about race. Calls for equal civil rights were part of a growing rallying cry, along with marches to end a foreign war and demonstrations filled with screams and tear gas, opposing a seemingly endless list of beliefs, causes and movements.

The times they were a-changing, but in Canada, at a pace as slow as molasses in January. Pressures to assimilate other peoples and cultures into whatever model was in fashion with the majority continued unabated — perhaps more politely but just as relentlessly as in the American “melting pot.” It was difficult to resist, impossible to accept, but necessary to endure in an attempt to preserve one’s self-esteem and dignity.

Walk in footprints carved by those who came before,

Their footsteps a map of who I am.

In the eyes of my kin, reflections of myself,

A mirror of our collective spirit.

— Dan David*

Pathways

Recently, an immigration lawyer and academic named Jamie Chai Yun Liew told a CBC Radio audience about her father’s experience as a “stateless” and “homeless” Chinese man.1

“My research has led me to understand that my father’s statelessness flows from British colonial hierarchies of citizenship based on race, the legacies of which are etched in law in different ways in post-British colonial states.

He was unlucky in that he was born as a Chinese person in a country that did not want Chinese people as citizens. He was called a British subject with no citizenship and no right to it either. This status is the reason why he became an arrivant in Canada.”

That was then, but Jamie Chai Yun Liew says even today there are millions of people who are denied citizenship in the land of their birth, who must leave in order to survive, are then unable to return, wind up unwelcome, and are denied citizenship wherever they might land.

“My father was able to escape his statelessness by migrating to Canada as an economic migrant. And while he holds citizenship here, the question remains: Does he belong?

Do I belong? When people migrate, they in a sense shed some skin and begin again when they have children in their new home. […] there’s a transitional moment between generations.”

Jamie Chai Yun Liew is describing an in-between space: a twilight zone between belonging and not belonging again; a situation of uncertain legal status, passport and citizenship; a place between hope and promise.

“I’m fascinated with this in-between space, how migration, the movement of people, challenges us to think of who we are. Growing up, I reconciled with the fact that my parents would not fully belong in Canadian society.”

This feeling of homelessness is more about emotional and psychological states than the lack of a physical structure. It reflects a sense of not belonging, of disconnection and instability.

Our roots are entwined with the roots of trees,

We are the earth, the sky, the breath of life,

In our unity, we find our strength,

In our diversity, we find our spirit.

— Dan David*

Protective colouring

A few years ago, I found myself wandering up and down the musty aisles of a used bookstore in Montréal. I wasn’t looking for anything specific. I was whiling away time before meeting someone for lunch. A book’s title caught my eye and triggered an old memory. It was a book written by an old friend and former colleague, Tony Chan. I decided to look him up and compliment him for that book, as it was something he’d always said he wanted to write one day. What I found was his obituary.

Tony once took me to a fabulous Chinese restaurant in Saskatoon for supper with his wife and daughter, Wei and Li-an. We talked about a lot of things that evening, but our mutual need to be genuinely ourselves topped the list. I think we both lived dual identities. We slipped on one mask to tolerate work in a mainstream newsroom. After work, we put on another mask for community, friends and family. I believe both masks hid who we really were and wanted to be.

I admired Tony because he advanced and changed more than anyone I knew then or now. He was third-generation, born in Victoria, British Columbia. By the time we met, he had already published a book entitled Gold Mountain about the untold Chinese history in Canada; been scouted for professional baseball; created and edited the cutting edge Asianadian Magazine in Toronto; helped organize national protests condemning a racist CTV News documentary that falsely claimed “foreign Chinese” had bumped Euro-Canadians out of universities; and produced a documentary about Chinese cafés in Saskatchewan. Later, he moved to Hong Kong, wrote more books and produced more documentary films before moving back to the U.S. and then to Canada, where he became a much-respected university professor in Canadian studies and communications.

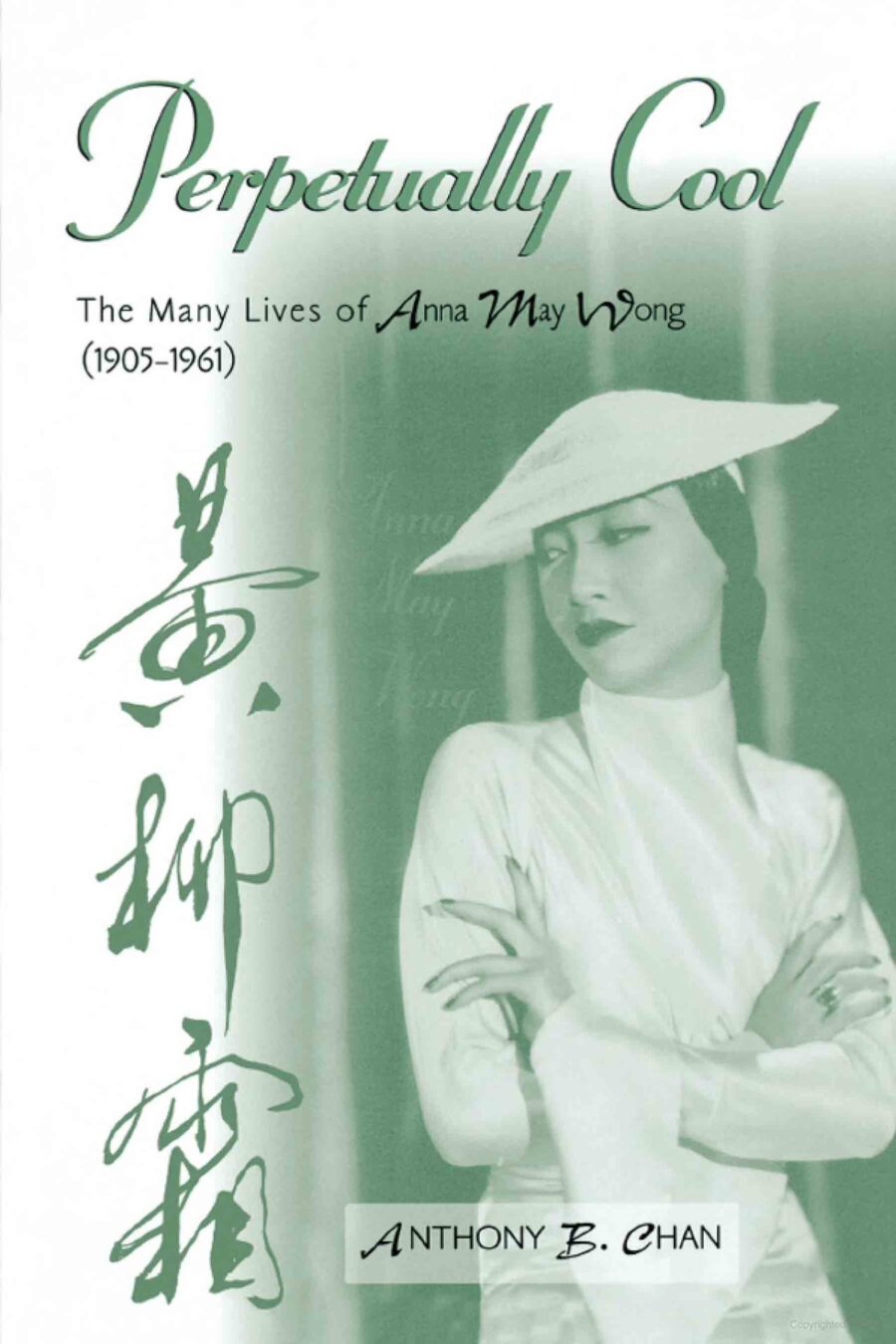

The book he talked about that long-ago evening in Saskatoon was about a Hollywood legend from the 1920s and ’30s named Anna May Wong. His face lit up as he told me about her and we picked over a hot-pot dinner. Tony described Wong as a bigger star than most at a time when European-Americans (Tony’s preferred word instead of “white”) routinely played Asian and Indigenous parts, and Blackface was common.

According to Tony, after returning to Hollywood from a trip to China, Wong reflected on her experiences in China and her career in Hollywood: “I am convinced that I could never play in the Chinese Theatre. I have no feeling for it. It’s a pretty sad situation to be rejected by Chinese because I’m ‘too American,’ and by American producers because they prefer other races to act Chinese parts.”Yet here she was, her name in top billing as the star of major motion pictures — even starring with other Chinese actors in films about Chinese life. Nothing like that would happen again until Bruce Lee in the 1970s paved the way for major movies like Crouching Tiger, Hidden Dragon (2000), and more recently Crazy Rich Asians (2018).

Not a Lotus Flower

“Wong was the first internationally-acclaimed, Asian-American female film star,” Tony Chan wrote, even though Hollywood and the media tried to pigeon-hole and limit Wong as a “Dragon Lady” and a “China Doll.” Wong refused to accept these labels because, besides a steely determination, she had a firm belief in her own talent as an actor, an unwavering sense of identity, and a clear vision of who she wanted to become.

“She was cast in stereotypical supporting roles in her early career and left Hollywood to further her talents in Europe starring in notable roles in Piccadilly (1929); Chu Chin Chow (1934); Daughter of the Dragon (1931) and Josef von Sternberg’s Shanghai Express in 1932 with Marlene Dietrich.”

– Anthony B. Chan, Perpetually Cool: The Many Lives of Anna May Wong (1905-1961), 20032

“[Anna May Wong] mesmerized audiences from Hollywood and London to Berlin, Paris, and Vienna with more than sixty films. Her stage career took her to Australia, Austria, Denmark, Italy, Scotland, Sweden, and Switzerland. Even more remarkable, she sometimes performed in the languages of the countries in which she worked. Her spoken German was legendary. Her cinematic demeanor was detached, cool, and hip. The woman had style!”

Pure Tony Chan, right there in that last sentence. That’s why I liked him almost from the moment we met. We thought alike in more ways than we didn’t. We may have argued about little things but we agreed on so many of the big things, like the lack of “minority” representation in newsrooms of every medium — from print to broadcasting to film — at every level. Our peoples just weren’t there in word, voice or face. He and I also reserved the right to disagree and question even our own ideas.

Tony Chan looked for stories that celebrated Asian people who were ignored or maligned by the mainstream, individuals who refused to meekly go along with whatever labels and limits society tried to build around them. Instead, his heroes found ways to escape, to achieve their dreams, to belong to something they created for themselves despite discrimination and racism. In short, he looked for people who — just like himself — wanted to be free of the restraints that European-American and European-Canadian society placed on their ideas, beliefs, stories and even identities.

I shared with Tony a dual sense of purpose and belonging that resulted in a form of split personality.

I shared with Tony a dual sense of purpose and belonging that resulted in a form of split personality. We were both firmly grounded as sons of our particular cultures and traditions. This allowed us to straddle and inhabit different worlds and work with the rest of society. It was never easy, though. We often vented our frustrations with how mainstream Canadian journalism wanted us to conform, to voice its beliefs about who we were as Chinese and Indigenous peoples. How we felt we had to talk like, look like, dress like and even think like them to fit in, be somewhat accepted — as journalists.

We complained to each other about how we had to explain over and over nearly every little thing that was so everyday obvious to us — like the impacts of the Chinese Head Tax or Canada’s Indian Act — and how it sapped us of energy, enthusiasm and the will to continue. I can’t tell you how many years I was asked to do a story that answered questions like “What do Indians eat at Thanksgiving?” or “How do Indians celebrate Christmas?” Tony had similar experiences.

Why did we suffer such ignorance? We felt saddled by the need to correct Canada’s erasure of so much of our histories and stories, and by its abject failure to teach its own children about how their country was built and why. We felt that this should have been journalism’s job as well. Instead, we were expected to confirm — not upset — preconceived notions and prejudices about our peoples. How could we quit with so much at stake?

I believe we each found our own separate but eerily similar ways to survive. Tony described it best, as usual, during an interview for his book Perpetually Cool.

“Somebody wrote a review of my book on Amazon, and one of the things he said was that Anna May Wong was a member of the Christian Scientist church — so how could she be a Daoist? See, European Americans don’t understand that as a Chinese, there’s no separation. You can be a Daoist, because it’s a philosophy, right? And you can be a Buddhist, which could be a religion and could be a philosophy, and then you could be a Christian. It’s not either/or. See, this is the problem. You’re either American or you’re Chinese — no, no, no. Anna May Wong proves it to me. You can follow two paths. You can be Chinese American. You can be a US citizen or neither. And I surmise that she was neither.

After she left China, and she became more Daoist, and all the things she said were very Daoist. She really became Anna May Wong. There was no race, no ethnicity, no color, no nothing — there was no citizenship attached to her. And once you do that, you know what happens? You adopt your own persona. I know a lot of people are going to criticize me for the Daoist chapter, because they don’t get it.”3

I think Tony’s personality and instincts — undoubtedly thanks to the examples of his parents and ancestors — led him to a similar conclusion as Anna May Wong. Essentially, that you don’t need to sacrifice your being and belonging to become someone else, to exist in society, in the entertainment industry, in journalism and education. “You can follow two paths,” Tony told the interviewer. “And once you do that, you know what happens? You adopt your own persona.”

Kariwaroroks

I arrived at much the same place in my life. I reached back in my culture to remind myself who and what I was in a Kanienke:haka (Mohawk) word: kariwaroroks. It means “truth-gatherer.” It describes “runners,” people sent to bear witness to important events and happenings, for example treaty-making or “placing horns” (erecting a chief). Their responsibility was to relay the story back as faithfully and accurately as possible. In present-day terms, they were journalists.

We didn’t need to surrender our beliefs to be good journalists, teachers, writers, storytellers. “Truth gatherers” informed and interpreted events and the actions of people, from politicians to police and farmers. Our different perspectives added to the story — they didn’t detract from or distort the story. They filled gaps that the dominant society had excluded or tried to erase.

One final memory. I had an “old-school” assignment editor. He made it clear to all in the newsroom that he’d decided I didn’t belong there. I’d just landed. Dropped off in the middle of the night on the last flight in, nearly broke, nowhere to stay, no one from work to meet me. Not an encouraging sign at the start of a new job.

I did every lousy job this editor threw at me. No complaints. Lots of subtle insults from others. But that changed the more I knuckled down. That assignment editor, on the last day before retirement, took me aside. He said exactly what I’ve told you — that he felt I didn’t belong. Not because of anything I’d done but because I was an “Indian” and had no business being a journalist. It wasn’t the first time I’d been told that and it wouldn’t be the last. But his next words nearly had me in tears.

“I was wrong,” he said. “You’ve done everything I asked and more. You took terrible stories and made a silk purse out of a sow’s ear. You belong here.”

I belong to the stars, the moon, the endless night,

I belong to the dawn, the light that breaks the dark,

I belong to my people, my family, my tribe,

In their arms, I find my home, my place, my pride.

— Dan David*

*Note: From Dan David’s poem, Belonging.

References

- CBC Ideas with Nahlah Ayed, Cultivating Community, Citizenship and Belonging | Jamie Chai Yun Liew, June 20, 2024

- “Anthony Chan’s 2003 biography, Perpetually Cool: The Many Lives of Anna May Wong (1905–1961), was the first major work on Wong and was written, Chan says, ‘from a uniquely Asian-American perspective and sensibility.’” (Unknown source, quoting from Chan’s Introduction to Perpetually Cool, p. xvii.) https://www.google.ca/books/edition/Perpetually_Cool/CUJI-hFSGNIC?hl=en&gbpv=1&printsec=frontcover

For more on Dr. Anthony B. Chan:

http://www.vmacch.ca/beta/anthony_b_chan.html

https://acam.arts.ubc.ca/anthony-b-chan-1944-2018/ - UCLA Centre for Chinese Studies, The One, The Only and The Perpetually Cool Anna May Wong, Interview with Anthony B. Chan, by Shirley Hsu, 2004

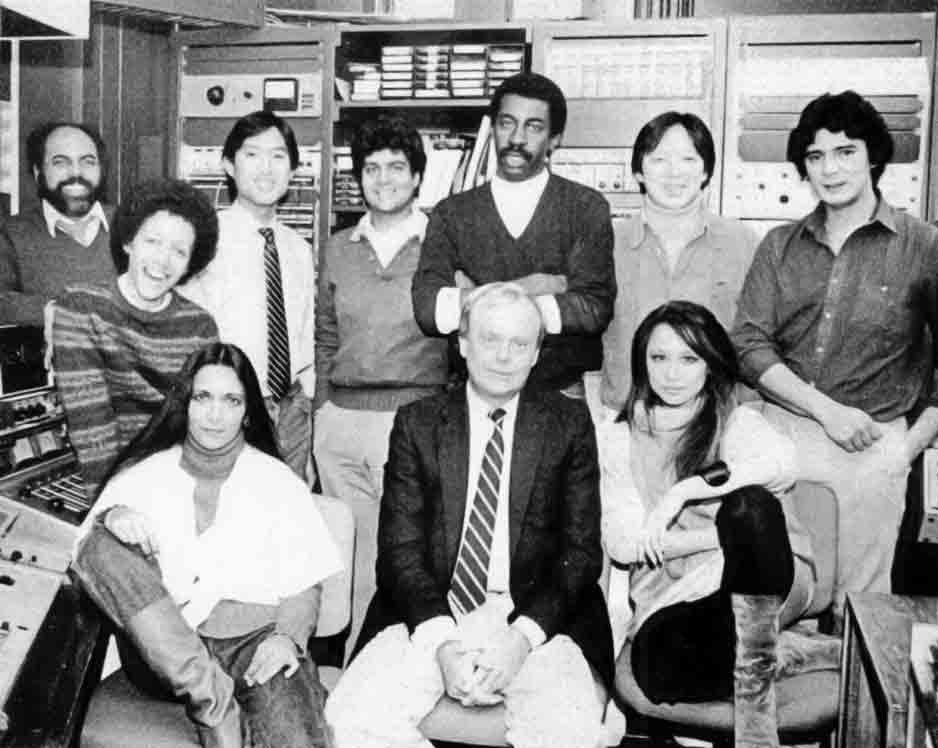

Back: Paul Winn, David Lam, Paul da Silva, George Boyd, Tony Chan, Dan David

Front: Claire Preito, Deepa Mehta, Tim Knight (CBC), Jari Osborne