The past is not another country

Colonialism isn’t dead, declares Simukai Chigudu, the author of the article quoted above. Reports of its demise have been greatly exaggerated. It’s not taking a nap. It isn’t on life support. It’s alive and well, thriving all around — if only we dared to look.

Colonialism is in plain view. It’s in the names of streets and buildings, celebrated with statues and plaques, and on the gates to parks and walls of stadiums. Montréal changed the name of one street from Amherst to Atateken, and one would think from the media hoopla that an ugly page of the past had been turned and the city was on its way to a rosy post-colonial future.

Not so fast, Chigudu contends. Using his own life experience growing up in apartheid Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), he describes how deeply the colonial mindset embeds itself not only in the psyche of the oppressed but also in the minds of the oppressor.

For Chigudu, there has been a constant stripping away of assumptions that he belongs to a lesser people, less worthy, less equal. Over time, he has questioned why he can’t be just as good, just as worthy — not only of respect, but also of self-respect. It’s an internal struggle colonized individuals experience to varying degrees. Many seek to understand colonialism and how it affects them; some rebel and demand restoration or restitution; others accept the situation, assimilate and survive.

Less obvious, because apparently there’s less reason, is the struggle by the colonizer (or settler) to change or decolonize their own minds. This is more difficult because… well, why should they change? After all, a colonial mindset is what they are taught and what they consider normal life should be. Life is good, filled with prospect and opportunity. They have stories that confirm their proper places in society — stories of discovery and struggle to tame a hostile but empty land and build a country to its full potential.

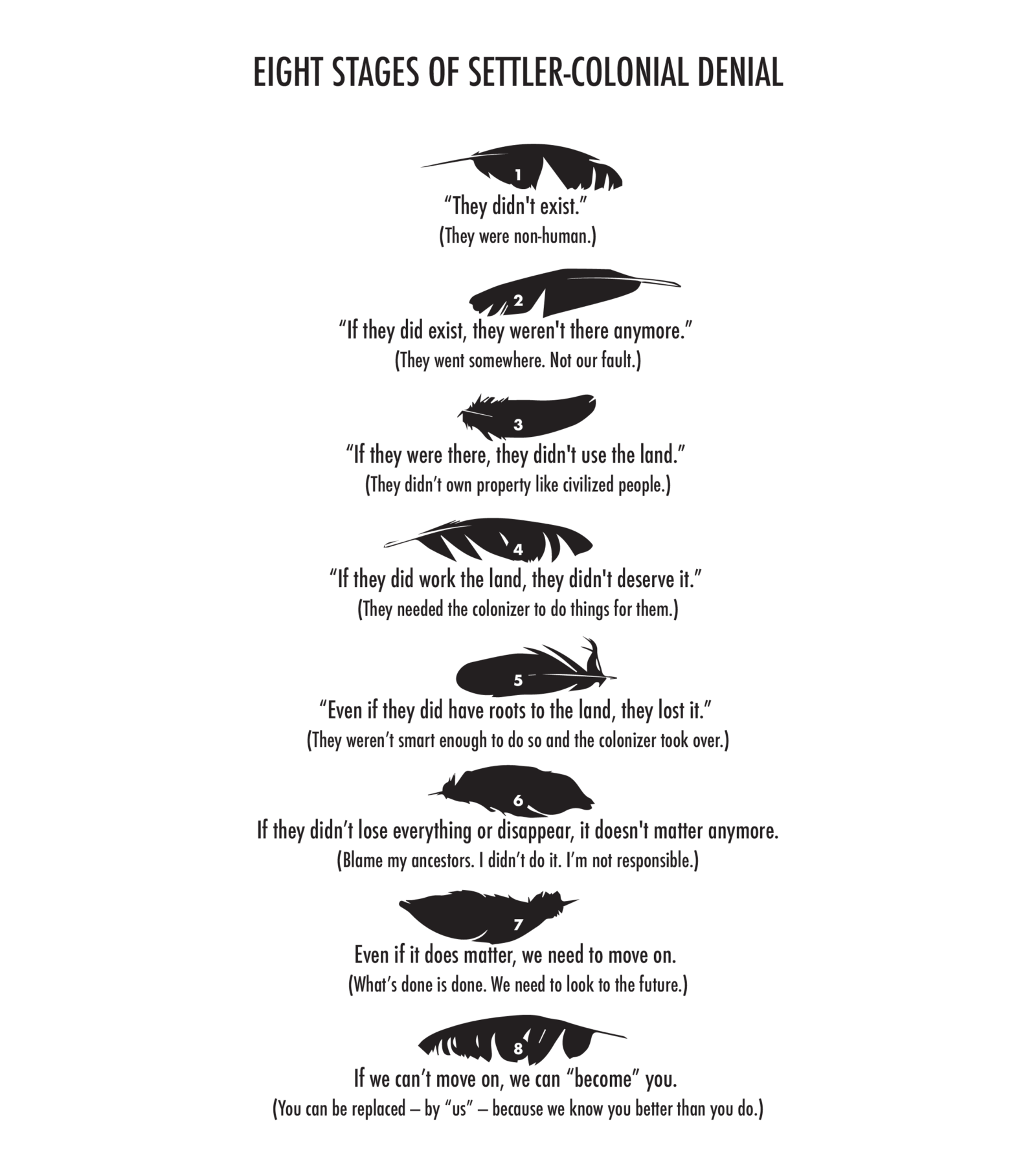

The contradictions in national myths, including Canada’s, may be dismissed or debunked, but not easily. They are stubborn, thanks in part to a pattern of behaviour some call “the eight stages of settler colonial denial.” The “they” in the following are the colonized or Indigenous peoples who experience(d) some or all of the following:

On a personal level, I have an identification card that I try to keep hidden in a drawer at home. It’s a constant reminder that I am not de-colonized, not self-determining, not free of Canadian paternalism. Welcome to the world of the Indian Status Card.

The status card denies me citizenship with my Mohawk Nation, one of the Six Nations (Haudenosaunee) Confederation, a democratic federation that pre-existed New France and New England. It insults our dignity by refusing to recognize my peoples’ deep roots into our ancestral territories and insists instead that we exist at Canada’s pleasure on “Crown land” called “reserves.”

That card symbolizes a system that creates separate, tightly controlled regimes for Indigenous health, housing, education and nearly every other facet of life while denying inherent rights to control our own programs, governments, political and economic systems. Token gestures toward self-determination are the standard.

Status cards are a product of the minds that created the 148-year-old Indian Act. It was predicated on the assumption that Indigenous peoples would eventually disappear as independent entities, eased into oblivion by Canada’s beneficent paternalism or “civilized” and assimilated into the general population. Indigenous roots to lands and resources would then be completely eliminated, a long-term objective of colonialism.

My status card is about to expire and — crazy thought — what happens when it does? What happens if I decide to burn my status card instead? Will I become like that Norwegian Blue Parrot of Monty Python fame? Would I cease to be, become bereft of life, join the choir invisible? Will I become an ex-Mohawk?

“What colonialism does is cause an identity crisis about one’s own culture.”

Lupita Nyong’o3

Colonialism isn’t something to joke about. It has dispossessed and destroyed independent and self-sufficient Indigenous nations around the world — from the Americas to Africa, Asia and the Pacific.

In this country, wave after wave of plagues decimated Indigenous populations. Soon after Confederation, Canada decided to “do away with the tribal system and assimilate the Indian people in all respects with the inhabitants of the Dominion.”4

The term “genocide” wasn’t coined until after World War II, but there’s no doubt genocide was practiced against Indigenous populations in Australia by Britain, in Namibia by Germany, and in other parts of the world by those and other European nations, triggering conditions that resulted in waves of migration by peoples seeking new lives and survival.

Canadians consider this system of domestic colonialism “normal” without really knowing why. We’ve all been conditioned to believe this is a mutually beneficial situation for everyone, thanks to the education system and mass media.

“The myth of integration as propounded under the banner of the liberal ideology must be cracked because it makes people believe that something is being achieved when in reality the artificially integrated circles are a soporific to the blacks while salving the consciences of the few guilt-stricken whites.”

Steve Biko5

However, things are changing. Indigenous peoples are not idle anymore and, increasingly, groups of marginalized peoples are beginning to understand why. They’re remembering indignities to their own peoples and cultures (due to colonialism) and connecting their experiences to similar outrages here and now in this country.

Anti-hijab and anti-kipa discrimination is blatantly ridiculous, so deserving of ridicule that it’s hardly worth mentioning. Except in Québec, where these discriminations and insults to human dignity are somehow deemed normal and even acceptable. They’ve been codified and, as of 2019, really are the law.

Less obvious but just as obscene is token hiring that checks those all-important “DEI” (diversity, equity, inclusion) boxes, and confirms red lines in housing and real estate to ensure that only the best people are allowed to buy or rent. There’s “carding” by police to control “gang-related activities” based largely on skin colour and neighbourhood.

The very walls in legislatures and parliament, the ink in courtrooms and tribunals, and the blackboard chalk in classrooms — all exude colonial mindsets deemed sacrosanct over the past 350 or so years. They designate certain people worthy of protection while others are… um, not so much.

The rules aren’t written but they are understood. They articulate and express the ways things have been and always should be, according to colonial gospel.

Colonialism isn’t one thing or a dozen things — it is an entire network of inter-connected systems built on a foundation of white supremacy.6

It’s a system that is also self-propagating and self-protecting and refuses to change quickly, quietly or without kicking up a fuss. Colonialism remains largely unchanged in part because it has embedded itself deep in the minds of those it exploits. It does this by swapping memories of violent dispossession, slavery and even genocide for fairy tales about partnership, mutual benefit and shared futures.

Newcomers from different lands, whether immigrant, refugee or asylum-seeker, are taught to believe and willingly accept this rosy alternate reality. These myths are also designed to lull such newcomers (settlers) into a false sense of security, assuring them that the system is doing what it is supposed to do. The result is a citizenry blissfully unaware of major cracks increasing in size and significance throughout the nation’s foundations. One person’s experience with colonialism 20 years after apartheid officially ended in South Africa is shared here.

A polite form of colonialism

I first met Dorothy Christian in Toronto so long ago that I can’t remember when or where. Our paths crossed again, sort of, during the Oka Crisis in 1990 — now known as the Mohawk Resistance or the Kanehsatake Resistance.7

I stayed behind the barricades with family at Kanehsatà:ke that awful summer. Dorothy was on the outside in a hotel room, using the telephone to reach people who knew writers and celebrities like Margaret Atwood, to help find a peaceful way out of the violent standoff at my small Mohawk community in Québec.

After the Crisis, she found herself heading home to Toronto, alone and driving down Highway 401. She was weeping uncontrollably, feeling betrayed, wanting to quit Canada. I knew exactly how she felt.

“And I was just really angry because I kept getting flashbacks of the helicopters. You know, the military and all of that was just in my head. And I was bawling, you know, crying and swearing and screaming.”

Dorothy’s words jog a memory of something she wrote for the Aboriginal Healing Foundation in a book entitled Cultivating Canada: Reconciliation through the Lens of Cultural Diversity.8

“After 1990, I wanted to leave this country which had demonstrated such hateful behaviour towards us, but then I thought, ‘Where would I go? This is my homeland. This is where my people have been for generations and generations!’”

Dorothy Christian

“Since then I have often wondered what immigrants think when they come to this country. I wonder what it feels like to leave their homelands, especially the more recent immigrant groups who are largely non-white and are forced to leave their traditional lands because of war, political instability, or other untenable circumstances.”

She still feels a sense of betrayal, though she’s managed to channel her pent-up anger into helping people understand Canada’s darker side — not to ruin their dreams but to temper their expectations with healthy doses of reality.

Dorothy Christian works with people from other cultures and shares stories about their experiences and this has helped her deal with her own frustrations and nightmares of conflict and anger. She finds that her work with other marginalized peoples has been cathartic. Their strength and resilience, compassion and humanity have encouraged her in return.

Those shared experiences and examples have renewed her own sense of identity and purpose and helped her value even more her Secwepemc and Syilx cultures.

Degrees of difference

Zainab Amadahy was born in New York City. Her father described the family as “African American, Cherokee and Seminole” with roots further south in the state of Virginia.

Zainab found her way to Toronto where she’s been active with “coaching, mentoring and community work. She is a prolific author of futurist novels, nonfiction publications and screenplays.”9

There’s a line in a magazine interview with Zainab that caught my eye.

“I wanted to branch out a little bit and do a story because of Indigeneity,” she wrote.

“I mean, we’re all different. Everybody, every nation, every culture has sometimes significant differences but there is also a thread that runs through all Indigenous cultures, that we see in each other. We recognize it in each other, and it feels like home when we find that in each other.”

Zainab doesn’t confine “Indigeneity” to Canada or even the Americas. She extends the definition to Indigenous peoples and nations on other continents around the world. In her view, this “connectedness” (for want of a better term) among Indigenous peoples is a lot more common than we might think.

Zainab also thinks this sense of connectedness happens to some extent among people that society has deemed “marginalized.”

“You know, I remember a time where the communities I relate to, Black and Indigenous, knew nothing about each other and never encountered each other.

That was colonialism at work, separating us onto reserves on the one hand and into poverty and urban ghettos on the other hand. We weren’t supposed to meet.

Zainab Amadahy

“They remember, you know — the colonizers remember back in the day, in the early days of colonization all over the Americas. When Black and Indigenous peoples got together, it caused them a lot of trouble. Slave rebellions.”

Zainab notes that there were always relations between runaway Black slaves and tribes like the Seminoles, who fought for decades against the American colonists and later the U.S. military. Runaways sometimes sought and found refuge with other tribes as well.

More recently, Zainab finds plenty of examples of different peoples finding common purpose and working together, especially in the arts.

“Art was definitely a place where Black and Indigenous folks came together, and migrants of colour too. We all very much wanted to learn about each other, really wanted to share stories, which is what artistic arts are all about. Sharing stories, right?”

She applauds efforts to work together and get to know each other better, but acknowledges the challenges. “It takes an intention. It’s not made easy for us. Not at all, right?”

This leads me to another article, this one written by Fatima Syed, a journalist. She described her surprise and mixed emotions when faced with this idea of connectedness at a memorial for the Afzaal family.10

A man deliberately drove his truck into a Muslim family out for a walk in London, Ontario. He killed four members of the Afzaal family: a girl and her mother, father and grandmother. Her young brother survived.

At a vigil for this family, Fatima Syed saw a man waving a “blue infinity flag” and wondered who he was and why the flag?

Curious, she decided to speak to the man and learned he was Métis and his flag represented the Métis Nation.11 He wanted the people at the vigil to know they weren’t alone, that he was there “in solidarity with the Muslim community and … our brothers and sisters.”

Fatima Syed was left wondering why this experience filled her with such grief and guilt, and wrote about her thoughts.

Around the same time, Canada was grappling with stories coming out of Kamloops, BC, about the discovery of more than 200 possible unmarked graves of Indigenous children on the grounds of a former Indian residential school.12

The convergence of these stories — the murdered Muslim family in southern Ontario, news about unmarked Indigenous graves on the other side of the country, and a lone Indigenous man expressing support for a grieving community not his own — left her with questions.

When my family moved to Canada from Pakistan, we weren’t told that this was a land built on genocide and erasure.”

Fatima Syed

“No one would want to move to such a country. Instead, we believed that Canada was ‘an economic opportunity.’ We believed it was ‘the greatest multicultural country in the world.’ We believed it was ‘a safe country,’” she added.

They didn’t consider they might be displacing Indigenous peoples, benefitting from a similar colonialism to that which subjugated their own peoples in their homelands, whether Pakistan, India, China, Australia, Kenya or South Africa.

“The more I reflect on the discovery of young Indigenous bodies on the sites of residential schools,” wrote Syed, “the more I realize that the term ‘immigrant’ is a misnomer. We, too, are settlers; we are people who chose to migrate to new, distant lands and establish permanent residence.”

If there’s a “saving grace,” she continued, it’s that they didn’t know, because they were never told or taught “[their] obligations to those (Indigenous) nations.”

“The sad jarring reality is that there are immigrants in this country that have never met an Indigenous person… Yet, here we are, today, immigrants and Indigenous peoples, mourning simultaneously alone and together, and grappling with our relationship with this country that promised to respect us, and never truly has.”

Roots of division

I pick up my conversation with Zainab Amadahy. I want to know why sharp divisions seem to exist between Indigenous peoples and peoples of colour (whatever their origins); why the divide, given their similar experiences with Canadian authority?

Zainab reframes the question: “Why don’t we interact with each other and share and learn from each other? I think to some extent that’s happening — I mean, you’re talking to a (Black) woman who is pushing 70, right? I remember a time where the communities that I relate to, Black and Indigenous, specifically, knew nothing about each other, never encountered each other… That was colonialism at work,” she continues, “separating us into reserves on the one hand, and into urban poverty ghettos on the other hand. So we weren’t supposed to meet.”

That was all part of the plan, in her view, even if most Americans and Canadians weren’t aware of it.

“There were Indigenous folks who were able to connect to Black folks and help them — help free them from slavery. They had access to people who knew the colonizers’ languages, who often came with weapons or knowledge of how to use weapons. So, yeah, it was trouble for the colonizer.”

According to her, colonists created laws to keep troublesome groups apart. They forced the removal of entire Indigenous nations, enacted laws forbidding or restricting travel, created “reservations” and ghettos, and imposed rules that determined who belonged where, what they could do, and what happened to those who broke the rules.

That system was called “Jim Crow” for African Americans and involved various acts regulating Indians (nowadays known as First Peoples).

“It was successful for a while,” Zainab continues, “but we’re not separate individual people. We are all connected. We’re all related. We’re all relatives. There’s an evolutionary impetus for us to connect, to learn, to be curious about each other, to seek each other out and to come together in meeting our collective needs as communities — in our case, in resistance, right?”

Of course, things have changed over the past 200 years or so. Slavery was eventually outlawed, and discriminatory and unjust laws fell, to be replaced by new laws and more policies that promised change, recognition, equality and inclusion.

Only up to a point, that is, according to Zainab. Progress was slow. Marches and demonstrations yielded grudging concessions for basic rights, but never achieved full recognition or restitution for stolen lands, or produced the promised benefits from shared resources.

Cue the myth-making department. Canada preferred a rosier narrative where Canada was a welcoming place, a fair country of law and justice, equality of opportunity and dignity.

Canadians conveniently forgot the Chinese Head Tax, Japanese Exclusion, the Komagata Maru incident, Africville, Indian residential schools and Inuit Relocation.

Canada wanted its history books to focus on “the two founding cultures” of French and English, the Mounties, building the national dream of a railway, UN Peacekeeping and universal Medicare.

Ask yourself: When and where did you first learn about those other stories?

Zainab Amadahy

As Zainab sees it, “Living under colonization is very dangerous for people. We’re taught to fear each other. We’re separated so we don’t know anything about each other… We’re still learning about each other.”

Modern colonialism

There are three policies that Canada calls evidence of its maturity as a modern state. Three policies that define its national character and identity. The first two policies, Bilingualism and Biculturalism, recognize the country’s twin colonial past, the “two founding peoples” theme.

Both attempt to reduce tensions between Québec and the rest of Canada. These two policies were responses to fading dominance by the Catholic Church, secularism during Québec’s “Quiet Revolution,” and increasing nationalism during the 1960s.

The third policy emerged about ten years later. Multiculturalism was a response to changes in immigration policy, resulting in more non-Europeans coming to Canada; a national welcome mat for different cultures and ethnicities.

Multiculturalism offered a little money for folkloric and small cultural activities. Later, the policy would support minority rights, oppose racism, and offer training among other things. Mainly, though, the policy was meant to smooth over a sometimes ugly past with a more rosy version of past and present.

Not everyone was a fan. Some thought it was more about “fluffs and feathers,” colourful costumes, exotic food and music, rather than meaningful examination of issues affecting minority communities.

Others thought multiculturalism impeded integration and eventual assimilation. Still others thought it allowed migrants to bring old-world disputes to new-world confrontations.

Same book, different cover

We have a terrible phone line when I catch up to Bonita Lawrence. The Mi’kmaw professor of Indigenous Studies at York University has researched, written and taught about multiculturalism, but also about race and anti-racism.

I begin by telling her that I’ve spoken with someone who said multiculturalism has helped integrate some immigrants and refugees into Canadian society, but that the policy created walls between and even within some of these same groups by pitting them against each other over funding.

“For funding, yeah,” she replies, “that really was the case.”

Lawrence is more fired up when she describes how violence against women of colour was practically ignored because the policy was so male-oriented.

She says communities’ wish to preserve languages was also overlooked, as the policy’s priority was integration not preservation.

Some groups did better than others.

“I think Caribbean people, especially in Toronto, were a lot less likely to be fooled by multiculturalism. Many had come over with the domestic worker program.” Lawrence suggests this made them more aware and critical of multiculturalism than most peoples of colour.

Recolonization

What Professor Lawrence really wants to discuss, however, is anti-Black racism and how multiculturalism favoured Black and other peoples of colour while elbowing aside and undermining Indigenous rights at the same time.

Back in 2009, she wrote a paper with Zainab Amadahy reflecting on relations between Indigenous peoples and Black people in Canada and the complex question of allies and settlers.13 Are Indigenous peoples and Black and other peoples of colour “allies or settlers”?

In an interview a few years ago,14 Professor Lawrence explained that a lot has changed since they published that paper. There’s much less division today between these communities. Indigenous peoples were front and centre at Black Lives Matter marches, and Black and brown people were prominent at Idle No More events.

Just as important, however, is the greater awareness and appreciation of why First Peoples of this land cannot be “people of colour” or “a minority community.”

“A lot of people who work with refugees, who are themselves immigrants, have said that in forcing a Canadian narrative on immigrants, it not only encourages an erasure of Indigenous peoples, but is also part of forcing people out of their own identities to try and force assimilation as quickly as possible.”

“Multiculturalism sidelines Indigeneity, because we become part of a multicultural mosaic.”

Bonita Lawrence

“Especially for refugees, learning more about Indigenous peoples and challenging Canada’s myth of being a country that welcomes all is better for their own identities — as well as for Indigenous people. Multiculturalism sidelines Indigeneity, because we become part of a multicultural mosaic.”

Multiculturalism sought to lessen Indigenous peoples, their relationship to the land and their very Indigeneity, by lumping them in with the many multicultural groups.

“I think a lot of Black activists today are very aware of Indigenous issues now. I know Indigenous communities are tackling anti-Black racism because it’s been an issue in many, many of their communities as well, so I do find that the two groups tend to work together more.”

Indigenous peoples view multiculturalism as simply another attempt to ignore and marginalize them along with peoples of colour, immigrants and refugees. In short, they see multiculturalism as just another way to continue Canada’s system of domestic colonialism.

This has me thinking about who gets to belong and what belonging means. If you’re a newcomer seeking refuge or asylum, or migrating to explore and find a new life full of opportunity, how does that work?

References

- Simukai Chigudu, “Colonialism had never really ended: my life in the shadow of Cecil Rhodes,” The Guardian, Jan. 14, 2021.

https://www.theguardian.com/news/2021/jan/14/rhodes-must-fall-oxford-colonialism-zimbabwe-simukai-chigudu - MEDIA INDIGENA, “A Plethora of Pretendianism: Pt. 1,” Mar 24, 2024.

https://mediaindigena.libsyn.com/a-plethora-of-pretendianism-pt-1-ep-343

A more complete version of “Eight Stages of White Settler-Colonial Denial” is found on p. 97 of Kim TallBear’s article at: https://journals.library.ualberta.ca/aps/index.php/aps/article/view/29425/21434 - Actor Lupita Nyong’o, quoted from an interview in Vogue, 2018.

https://www.vogue.com/article/lupita-nyongo-black-panther-vogue-january-2018-issue - Malcolm Montgomery, The Six Nations Indians and the Macdonald Franchise, Ontario History Vol. 57. Toronto: Ontario Historical Society, 1965. p. 13.

- Steve Biko (1946-1977), I Write What I Like: A Selection of His Writings. Johannesburg: Picador Africa, 2004.

- Mary Frances O’Dowd and Robyn Heckenberg, “Explainer: what is decolonisation?” The Conversation, June 22, 2020.

https://theconversation.com/explainer-what-is-decolonisation-131455 - Loreen Pindera and Laurene Jardin, “78 days of unrest and an unresolved land claim hundreds of years in the making,” CBC, July 11, 2020.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/montreal/oka-crisis-timeline-summer-1990-1.5631229 - Ashok Mathur, Jonathan Dewar, Micke DeGagné, eds., Cultivating Canada: reconciliation through the lens of cultural diversity. Ottawa: Aboriginal Healing Foundation (Canada), 2011.

http://www.ahf.ca/downloads/cultivating-canada-pdf.pdf - Zainab Amadahy, LinkedIn

https://www.linkedin.com/in/zainab-amadahy-a7833775/?originalSubdomain=ca - Fatima Syed, “As A Muslim, I Face Islamophobia. As An Immigrant, I’ve Failed Indigenous People,” Chatelaine, June 23, 2021.

https://chatelaine.com/opinion/immigrant-settler/ - Métis Nation

https://www.metisnation.ca/about/about-us - Courtney Dickson and Brigette Watson, “Remains of 215 children found buried at former B.C. residential school,” CBC, May 28, 2021.

https://www.cbc.ca/news/canada/british-columbia/tk-eml%C3%BAps-te-secw%C3%A9pemc-215-children-former-kamloops-indian-residential-school-1.6043778 - Zainab Amadahy and Bonita Lawrence, “Indigenous Peoples and Black People in Canada: Settlers or Allies?” in Breaching the Colonial Contract, ed. Arlo Kempf, 105-136. Dordrecht: Springer, 2009.

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/227255625_Indigenous_Peoples_and_Black_People_in_Canada_Settlers_or_Allies - Ashley Okwuosa, Interview with Professor Bonita Lawrence, “How can Indigenous and Black communities be better allies to one another?” TVO, Oct. 1, 2021.

https://www.tvo.org/article/how-can-indigenous-and-black-communities-be-better-allies-to-one-another