I had to park my car a few blocks away from Montréal’s Chinatown. I didn’t mind the walk. It was a sunny day. I head to this neighbourhood every now and then to buy groceries, things the store near home won’t stock. Walking back to the car, I noticed a Star of David on the side of an older red brick building.

I don’t know why but I stopped on the sidewalk, stared at the building, and thought about its untold stories. The building was sturdy and had a date in the brickwork, but I can’t remember what it was. It reflected an earlier time when buildings like this were more common. It looked more like an office building than a home or apartment building but maybe it was both for a family or even families. Who were they? Where did they go?

As a young student in Toronto, alone and lost in a city full of strangers, every now and then I’d wander through its Chinatown. I felt more comfortable because people there also had black hair, dark eyes and even sort of resembled family back home. Every now and then, I’d swear that person passing looked just like my older brother or youngest sister.

There too, I found houses that looked like they belonged to another time and people. A friend who lived a few blocks from Kensington Market had childhood memories of a Black neighbourhood now long gone. Further east, he told me the same street had once been the preserve of lefty whites. The last time I walked down that street, I was looking for a Thai restaurant located near a place that made soy bean curd.

What was it, I wondered, that drove marginalized peoples to collect into cultural clumps like these neighbourhoods? It didn’t matter whether it was in Winnipeg’s North End, Vancouver’s East Side, or the Côte-des-Neiges district in Montréal. Was it by happy accident or design?

“You know, at least in my experience in the community that I am from, I would say a lot of us do that.”

Iftekhar Ahmed is with Brique par Brique, a non-profit organization building community and affordable housing, with immigrants and peoples of colour in the Park Extension neighbourhood of Montréal. The group began 13 years ago taking action against discrimination in housing, health and policing. It continues that work but has evolved into advocacy for more affordable housing, social supports and activities that create welcoming spaces.

“It’s a mixture of things,” Ahmed replies to my question about what I’ve called “cultural clumping.” He says he can’t speak for anyone else or what they might do, but notes that “to some extent, when people come here, this culture and the traditions here are very different. There is a bit of a culture shock, and they kind of do go inward and just try to connect and relate to their own kind of people.”

It is, after all, a nation’s promise that puts multiculturalism as a major plank in its cultural policy. Come here, become Canadian, bring your recipes and festivals. Add your colours into the cultural mosaic that is Canada. Or so the official line goes. Less known or advertised is the pushback by some who resist change and even prefer white bread and mayonnaise to biryani and banh mi.

People look for a place where they can afford to live, a place where they feel comfortable raising a family. Someplace with a school, where their children can play in safety. A place with familiar people, food and cultural activities, and fewer stares and glares. A neighbourhood they can either move into or create.

“Yeah, I think there are lots of insecurities and the fear of losing their own cultural identity,” Ahmed continues. “And people, especially from Pakistan, tend to be very religious. So religion plays a significant part in this as well.”

He speaks as a Pakistani individual. There are others from other cultural groups who would say much the same thing. Another question: Are people gravitating into communities by choice to find comfort in numbers? Or are they driven into ethnic neighbourhoods seeking protection from discrimination and stereotypes?

Ahmed suggests it’s more likely people are looking for places they hope to find familiar and comfortable: “For them to be averse to the dominant culture, they have to be more exposed and interactive with the culture. And I feel a lot of them, not all of them, but a lot of them, don’t even interact to that level or put themselves out in that space. So I see them socializing mostly among themselves when they have free time. The only place where they would connect with mainstream culture would be at the workplace.”

“I think certainly the younger generation,” Ahmed explains, “would be more familiar and engaged with the dominant culture for obvious reasons. I’m talking about the older generation mostly, who likely are first-generation immigrants. They find it hard to assimilate. I don’t know if assimilate is the right word, but familiarize themselves and interact with the dominant culture.”

Iftekhar Ahmed says that doesn’t apply to him. Even as a first-generation immigrant, he says he wants to meet other people outside of his own cultural group.

“I want to interact. I actually am, to some extent, more part of the dominant culture in some ways. I mean, I do maintain my cultural identity. But certainly, my children were second-generation. They are very much part of the dominant culture, or interact with the dominant culture.”

“So you’re an explorer?” I ask.

“Yes, exactly.”

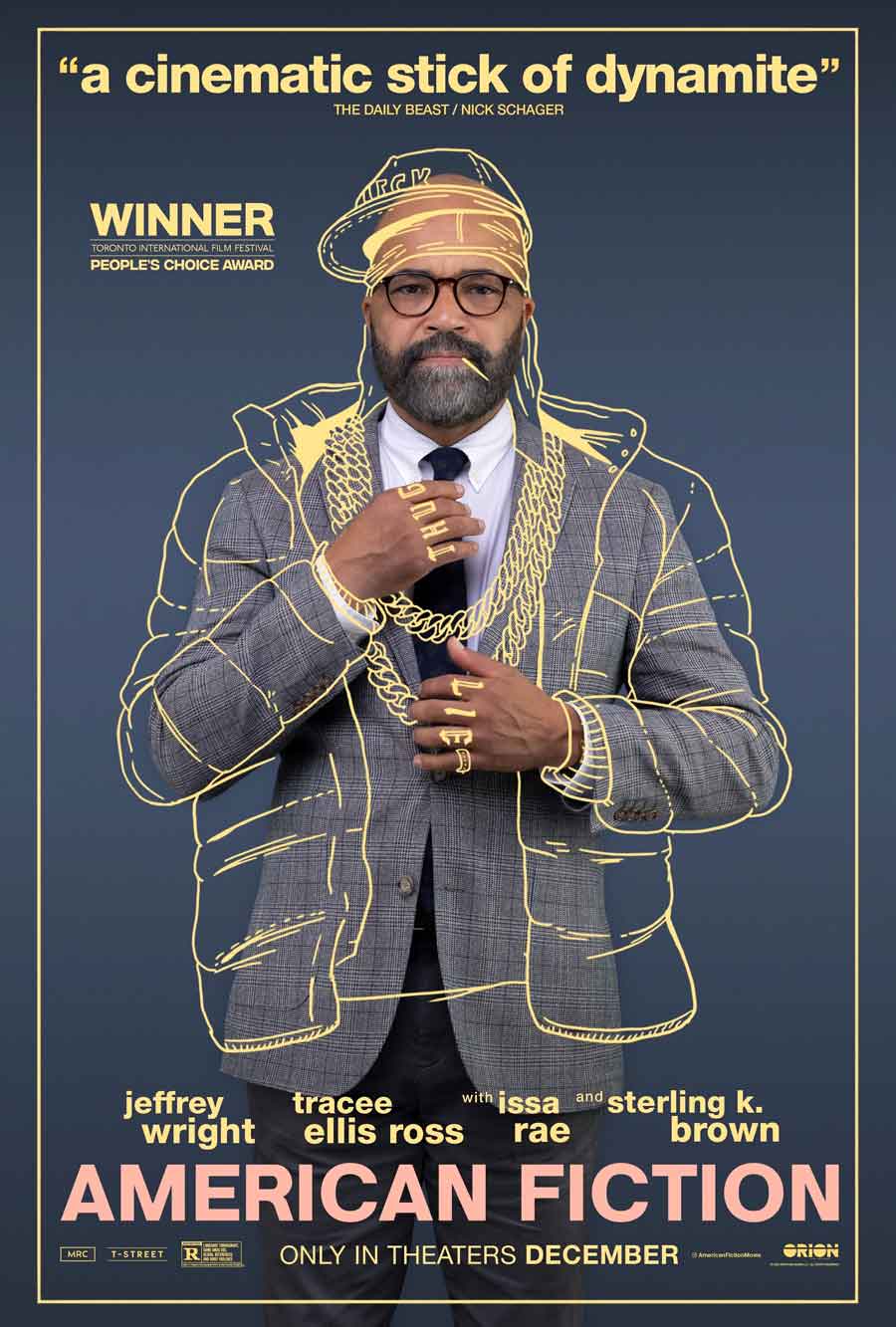

Two of my younger sisters insist on taking me to a movie. I’ve been burrowing into my computer screen too long, they tell me. Time for me to come up for some air. A drive to the West Island will do me good, they say. No arguments. I know better than to struggle.

Opening scenes in movies rarely get right to the guts of the story. There might be a slow zoom into a city or town, a downtown street or gravel road, an office or a kitchen. Pictures and sound slowly ease the audience into a story’s time, place and mood.

Not the film American Fiction.

Right off the bat, the first thing you hear and see is a teacher in front of a whiteboard.

“Okay, let’s begin,” he says. “Who wants to start?”

A student in a mostly empty college classroom says, “I don’t have a thought on the reading. I just think the word on the board is wrong.”

The picture cuts to the whiteboard and shows the title of a short story, “The Artificial N——,” by Flannery O’Connor, a satire about racial stereotyping.

“No,” the teacher replies about the word itself. “It still has two Gs.”

After a slight pause, the teacher continues. “If I can get over it, so can you.”

The student is white. The professor is Black.

The student stomps out.

The teacher is suspended from teaching. He’s exiled from Los Angeles to a book festival in Boston, a city he left a long time ago to escape his troubled family.

Shortly, in another scene, the teacher’s literary agent tells him that his latest manuscript has been turned down by multiple publishing houses and even by the publisher of his last book. The agent reads the rejection letter over the phone.

“He said, ‘This book is finely crafted with fully developed characters in rich language. But one is lost to understand what this reworking of Aeschylus’ The Persians has to do with the African American experience.’”

“There it is. There it is,” says the teacher.

“They want a Black book,” replies the agent.

“They have a Black book. I’m Black. And it’s my book.”

By this time, we all know this story is about race, racial stereotypes and the pressures imposed by mainstream society to make Blacks (and by extension, all racialized peoples) fit into familiar pigeonholes for the comfort, joy, and even profit of the mainstream.

American Fiction paints a bullseye on a specific form of hypocrisy in society that reinforces, promotes and celebrates racial stereotypes while studiously avoiding any mention of them. The film manages to describe society’s guilt about race, whether that guilt is earned, misplaced, or driven by self-interest and profit.

The moral of this movie is simple: We are all complicit, a little or a lot, whether we know it or not. We allow this racial hypocrisy to continue, as passive readers, listeners and viewers, and as paying customers that support, encourage and even applaud this hypocrisy. Maybe we are all, also, somehow responsible.

We turn people into caricatures of themselves. It simplifies things for us.

We love stereotypes. We boil down certain characteristics and personalities of individuals and then paint entire cultures and peoples with broad brushstrokes. We turn people into caricatures of themselves. It simplifies things for us. Cultural and racial stereotypes make the world easier to understand and to navigate for simple folks like me. We all do it no matter how much we pretend otherwise.

Who hasn’t heard about “Driving while Black” or doesn’t know about “the Talk” and variations of these themes depending on the neighbourhood, colour or culture? We live in a world surrounded by stereotypes that define boundaries not only of geography and culture but of belonging and safety, too.

Marginalized peoples swim in this common cultural fishbowl filled with familiar stereotypes. They surround us and are a fact of everyday life, part of the atmosphere we breathe and even accept as normal. We internalize stereotypes about ourselves. Worse, we impose stereotypes upon each other and upon other marginalized peoples, despite living in the same municipal or provincial fishbowl.

Racial stereotypes may be steeped in the past but they’re stubborn things to dispel or eradicate in the present. They persist no matter how many times individual success stories prove them wrong. Endless stories about “firsts”—the first doctor, the first lawyer, the first nurse or university professor—fail to debunk stubborn stereotypes. Stereotypes need only one “negative” example to erase the achievements and successes of all those individuals. They confirm in the minds of many that some people are inferior—including our own beliefs about others.

“Did you ever hear of such a thing? They don’t speak like the N—— back home.”

My “American” relatives came to visit before heading off to Montréal and the World’s Fair called Expo 67. They rarely came this far north. We lived a couple of hours further than the international border. I have no idea where we found room for all of them to sleep in the tiny house we shared with my grandparents.

Our visitors found Québec a bit too different, too foreign, too strange for their tastes. I mean, there were all those confusing signs and what was it with Québec and all those saints? Saint this and saint that. The prices were high, the money was funny and even the hot dogs were different. “They put coleslaw on the hot dogs,” complained one of my cousins!

What I remember most was their shock upon hearing Black people speak French.

“Did you ever hear of such a thing?” they asked each other. “They don’t speak like the N—— back home,” they joked. “Do all N—— speak French in Québec?”

Talk about stereotypes! They didn’t seem to mind white people speaking French, but what was it with all these Black people?

I was a high-school teenager, glued to the tiny black-and-white TV screen every night, watching the news about Alabama or Mississippi cops setting attack dogs on Black people marching for the right to vote. My radio tastes switched between Aretha and Buffalo Springfield, with lyrics etched into my brain that went:

“It’s time we stopped

Hey, what’s that sound?

Everybody look what’s going down.”

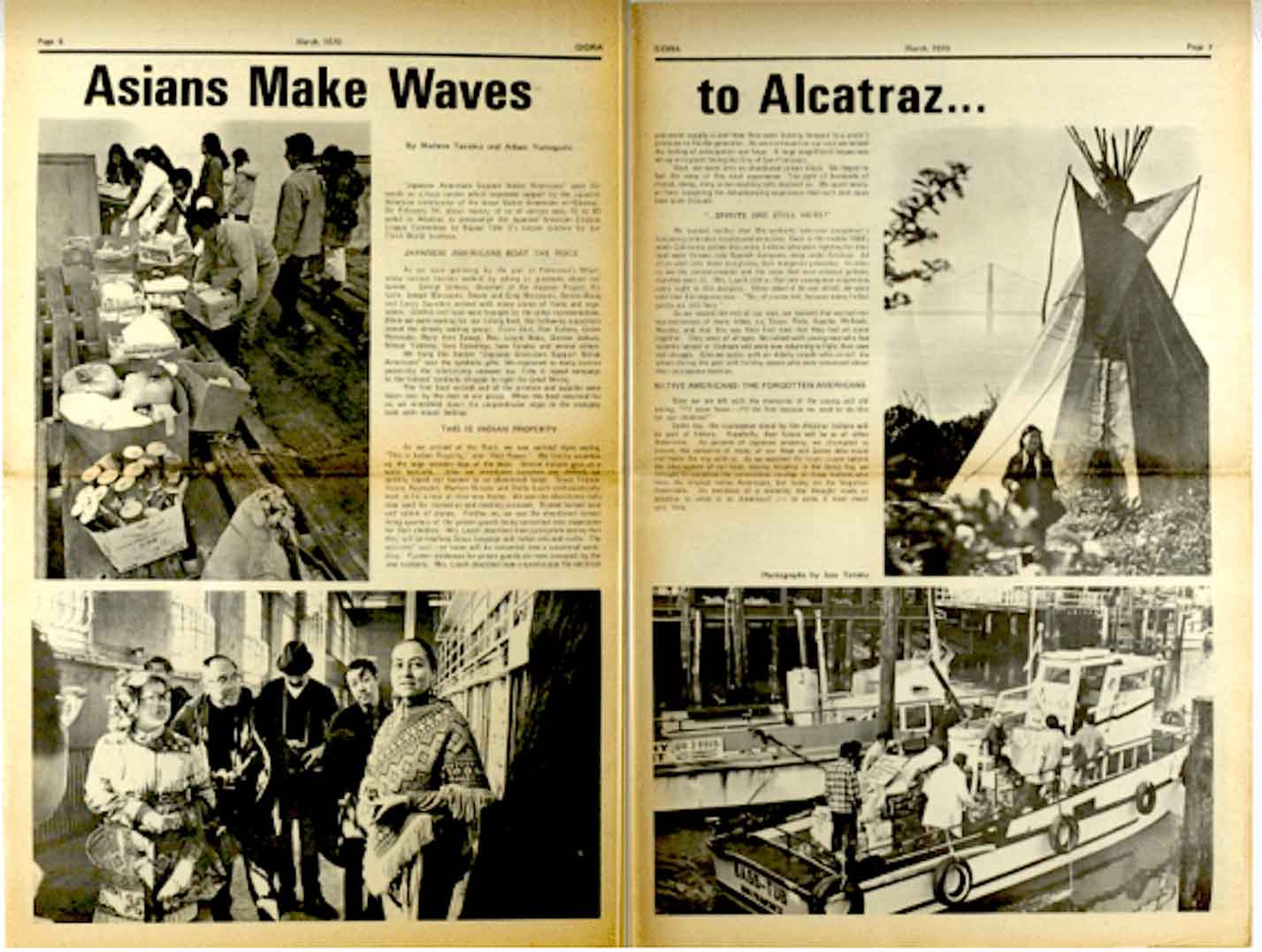

I was only just becoming politically aware about Indigenous rights. If I hadn’t overheard my parents talking about a cousin of ours who was one of the organizers of the occupation of Alcatraz Island, I might have zipped right by that seminal event. Knowing about it, though, led me to want to find out more about what came next. A standoff between the American Indian Movement and the FBI at Wounded Knee. The “Trail of Broken Treaties March” to Washington, DC, and an occupation of the Bureau of Indian Affairs building. It was all part of the same burst of anger and frustration with long-ignored injustices.

“Just being born Indian is a political statement,” I heard my dad say around that time. I thought to myself, what a profound thing to say. Much later, after I learned more about the struggles of other peoples, I wondered whether he dreamed up those words himself or was merely adapting something someone else had said, putting his particular spin on the words.

Most of what I remember about my parents are the books. Lots of books here and there and everywhere. More books on a terribly overwhelmed bookshelf that sagged and groaned under the weight, promising serious injury to anyone who dared sit on the couch underneath. Books and piles of newspapers, magazines and clippings clogged the hallways in the house.

They were always talking about something they’d read, seen or heard in the media. They didn’t just drop a few words and move on to the next subject. No, they dug deep into the issues of civil rights, treaty rights, various discriminations and the wilful blindness of authorities to their obligations. It never mattered if the issue didn’t deal with them, our people, or our community. It mattered because something was wrong. Period. End of story. As children, we watched, listened and learned.

They would talk about the Black Panthers in a similar way that they’d describe the American Indian Movement (or AIM). Both set up school lunch programs for hungry kids in the cities. Both tried to find decent housing for single-parent families. Both began programs to raise awareness about rights and instill a sense of pride too long denied just for being. As children, we watched, listened and learned.

Rita Deverell speaks in carefully considered clauses and pauses. She makes sure each sentence says exactly what she means. She’s a sometimes actor, a writer, former journalist, co-founder of a “fiercely multicultural broadcaster,” who has earned various awards. She’s also a constant advocate for “DEI and D” which she explains stands for “diversity, equity, inclusion and decolonization.”

One of her projects is Women in the Director’s Chair, which works to increase the number of Indigenous women and women of colour calling the shots in television and film production. Not the easiest task, she says, because gender can be just as stubborn a barrier as race in the industry.

Deverell says she likes to unsettle assumptions every now and again by introducing herself as a Black woman from the same Texas town as George Floyd, before launching herself into a presentation. Floyd, if you remember, was murdered by a police officer who kept his knee on the back of his neck for over nine minutes during an arrest. Floyd’s last words were: “I can’t breathe.” His killing sparked nationwide protests and the birth of the Black Lives Matter movement, and raised questions about racial justice in both the US and Canada.

We’ve known each other for years. She was a sounding board for my frustrations during my early years as a journalist. She’s been a friend ever since. Today, I want to ask her why we marginalized peoples on the fringes of society seem content with staying in our separate enclaves.

I ask her, “Why is it that marginalized people, Black, Indigenous and People of Colour, don’t cooperate more, work together more? Wouldn’t our combined voices be louder, have more weight? Why don’t we unify? Wouldn’t change happen quicker?”

The other thing about Deverell is this: She likes to tell stories to explain things rather than offer short answers.

She says she’s trying to convince a group of filmmakers to consider hiring more women of colour behind the cameras. They counter with excuses: They can’t do that. It’s not their decision because they don’t actually do the hiring. It’s not their responsibility. That’s a decision somebody else makes.

That’s ridiculous, she counters. Of course you have a choice. “We are all always making choices all the time about who we’re going to work with, who’s going to be on committees, and this and that, whether it’s paid work or volunteer. Who we’re going to talk with, who we’re going to have dinner with. You don’t have to be in charge of a feature film that’s going to hire 200 people to be making choices about who you’re finding out about.”

This is a story about people in authority looking for a path of least discomfort.

To Deverell, this is a story about people in authority looking for a path of least discomfort, unwilling to introduce themselves to people who are different from themselves. They justify doing the same-old same-old because that’s the way things have always been done.

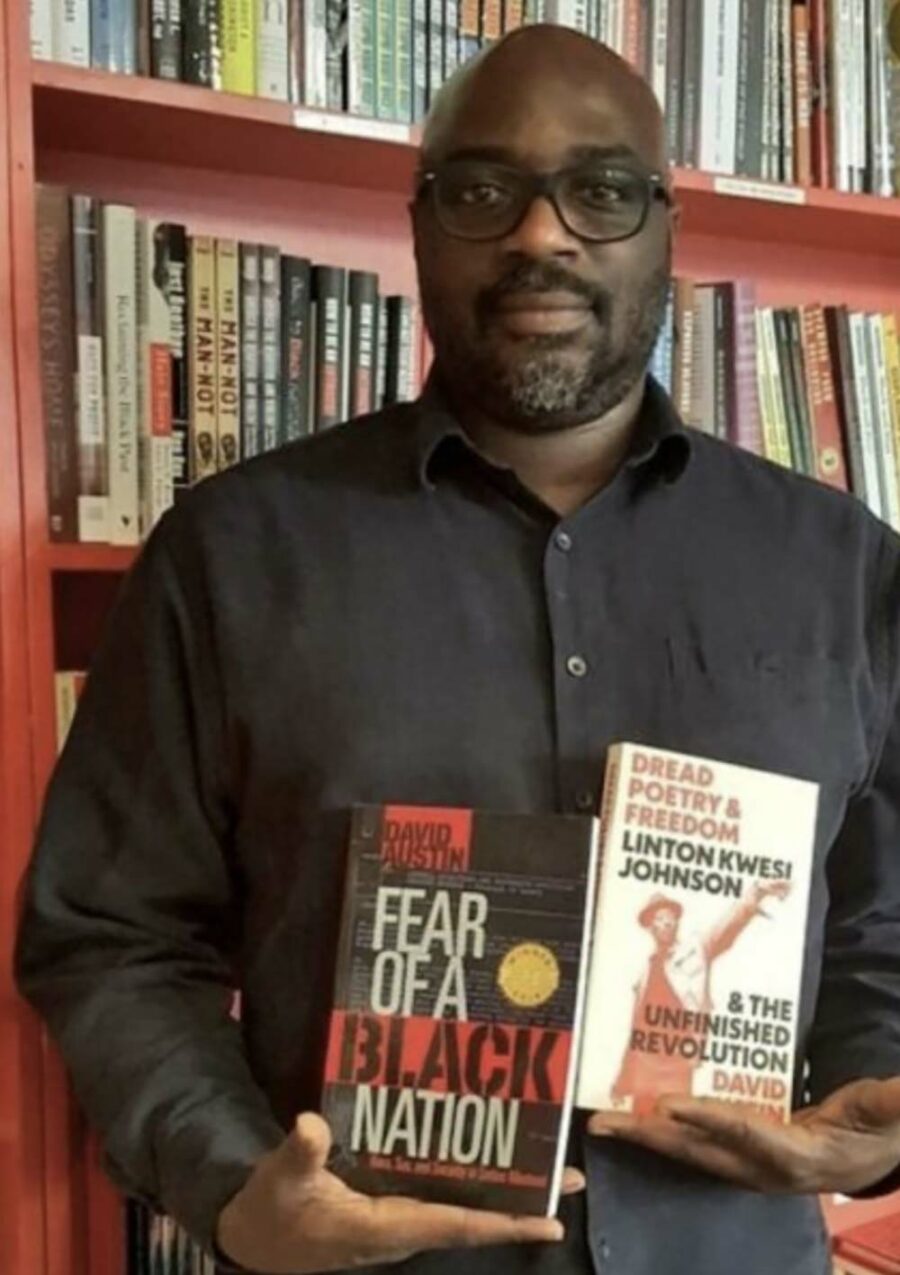

“So with this group, at this moment we’re going through, maybe we really don’t want to find out anything. And so staying in your comfort zone is one reason we can’t get to know each other.” This is Deverell’s way of explaining why cross-cultural unity may be possible but requires understanding, a commitment to change, and lots of work. I tell her about a conversation I’ve had with Professor David Austin. He teaches history at John Abbott College in Sainte-Anne-de-Bellevue on the West Island. He’s an optimist but also a realist.

David Austin arrived in Montréal 34 years ago as a university student. Almost immediately, he became interested in a series of events such as the 1968 Congress of Black Writers conference and the Sir George Williams University affair the following year. In particular, Austin wanted to know more about a man called Roosevelt Douglas who seemed to be at the centre of everything. Douglas later became the Prime Minister of Dominica in 2000, but died less than a year after taking office.

The first time Austin met “Rosie” Douglas, he felt like he already knew the man. Douglas’s son, a student at Concordia, was a friend.

“I already knew about his father because he was one of the principal figures in the majority of the students’ projects and in what happened at Concordia [then Sir George Williams]. And he actually went to prison for his role.”

“But you know,” Austin continued, “when [Rosie Douglas] came out of prison, one of the things that he set about doing very consciously was to work alongside various Indigenous groups across this country, including across Canada, Wyoming, and California.”

“So the first time I traveled across the Mercier Bridge,” said Austin, “was when he [Douglas] visited here in 1993 or ’94. I traveled with him and saw the people, and it was like he was meeting old friends [at Kahnawake] who he had known from the 1970s. And, you know, that was one of those moments of potential longstanding political solidarity that was ruptured by the RCMP.”

Occasions like this indicate that some form of solidarity among marginalized groups might have been possible.

Austin says occasions like this indicate, to him at least, that some form of solidarity among marginalized groups might have been possible—maybe even with disaffected youth in Québec. Consider the time in history though.

The late 60s saw the rise of separatism in Québec, of the Front de Libération du Québec (FLQ) and of a wave of bombings. It was also when Canada saw Indigenous peoples resisting residential schools, the “60s Scoop” by child welfare agencies, and “Indian Affairs” paternalism with all of Ottawa’s control over almost every aspect of Indigenous life.

The federal Government considered both situations—the rise of Québec separatism and of Indigenous rights—as problems stemming from notions of collective rights. The solution, Ottawa decided, would be policies emphasizing “individual rights” while ignoring or removing “collective rights” at the same time.

It’s no coincidence that Ottawa tabled its “1969 White Paper on Indian policy,” which would remove the collective rights of “Indians” from the Constitution, scrap “reserves,” tear up “Indian treaties” and get rid of “Indian status.” Meanwhile the RCMP designated “Indians” a national security concern and, according to Austin, “brought in from the United States [someone] who was African-American and also somebody who was a member of AIM, but [who], the entire time, was also [working as] an agent.”

The agent’s job, Austin said, was to spy on [activists] and disrupt any notion of an Indigenous-Black alliance—especially at this time in Québec.

Despite all that, during this same period and with the occupation of the Sir George Williams computer lab by Black students, there was a real possibility of some form of unity, in Professor Austin’s view. “Sometimes I think it’s useful to revisit history to see how there are past precedents and also [examine] what caused them to fail. I mean, [the failure of efforts to unify both movements] had nothing to do with the relations between the two groups; [it had] more to do with outside interference.”

There is another perspective about that very same event that occurred 56 years ago in Montréal.

Kahentinetha Horn has been a thorn in the Québec government’s side since Expo 67, the Montréal World’s Fair. Today she’s involved in a fight between McGill University over unmarked burials on the grounds of the old Royal Victoria Hospital.

If Hollywood made a movie about her life, the promotional blurb might read something like this: “The fashion model who became an outcast who became a warrior.”

We have trouble connecting. At one point, she hears some weird feedback on her phone and asks if I’m tapping her conversation. But she has good reason to wonder, even if it’s a joke, because she’s been someone Canadian authorities have kept an eye on for most of her life.

“Tell me about Alcatraz,” I want to know.

“Well, I wasn’t there that much,” she replies, before jumping into story after story, about Marlon Brando and Buffy Sainte-Marie, about her fundraising adventures up and down the California coast.

“Tell me about the Brown Berets,” I prod.

“Oh, they were Chicanos, Mexicans, but most were Indigenous. AIM (the American Indian Movement) was there, too. We got along with the Brown Berets better than with the Black Panthers because they knew more about our cause, you know. The Brown Berets were Indigenous. The Panthers wanted to take us over, to speak for us, to put some of our people up front at their rallies, you know. But to represent us and not let us speak for ourselves.”

This is a theme that continued a couple of years later when she was invited to speak at a rally supporting the occupation at Sir George Williams University in Montréal. “Stokely Carmichael [a Black civil rights advocate] was there to speak as well. I remember him and someone else. They wanted me to say that we were all one big group. And I wouldn’t. We couldn’t be.”

“Why not?” I ask.

“We weren’t against them. We supported what they were trying to do. They were fighting for their rights. But they wanted to speak for us and that wasn’t going to happen. You know, they were against racism. Okay. And they wanted to be treated like equals. That wasn’t what we wanted.”

“We didn’t want equality. We wanted our rights to be recognized as Mohawks, as Indigenous peoples, not equal rights as Canadians, you know. We were different and we had to be seen to be different.”

“I remember I said that at the rally. They didn’t like that. But I had to tell them that I couldn’t say what they wanted me to say. We weren’t against them but they couldn’t speak for us. We had to speak for ourselves.”

Kahentinetha said that she wasn’t exactly kicked off the stage but she was “booed” off.

I started this journey proposing—believing—that we marginalized peoples living on the fringes of society are somehow similar.

Believing that we’ve lived similar lives, had similar hopes and dreams of the future. That we’ve faced similar obstacles and pressures. I found some examples in our common histories of generosity and empathy for the suffering of others despite our own tragedies.

Are we all the same or even similar? I found some agreement from people like Rita Deverell.

“Well, of course we are. If we’re talking about the basics of human biology, deep down inside we are all the same. Deep down inside we’re also all different—and that can be part of your consciousness as well.”

I’ve also heard from others who say that we cannot be the same, that we are fundamentally different because of one unavoidable fact. Indigenous peoples are indigenous to this land. Everyone else—Black people, brown people, Asian peoples and so on—are “settlers” who came to Canada like everyone else, whatever their circumstance and story.

People like Kahentinetha tell me this is what everyone needs to know and to accept.

“They want to be seen as equal. They want to have equal rights as Canadians,” she said. “That’s okay. What we need them to know is that we are from here and not from anywhere else. No one brought us here. We were here. We’re still here.”

Does that mean we can’t learn from or work with each other, support each other? I don’t think that’s what she means. I believe Kahentinetha is saying that there are Indigenous peoples… and then there is everyone else. We can be allies and support each other. But don’t assume to speak for Indigenous peoples.

I know exactly what she means. Too many times, too many groups want to use Indigenous peoples as handy props, to carry banners at the front of parades and demonstrations, to be just another box to check off on a list of “must includes.” Does this mean unity or at least cooperation is not possible?

Maybe we should give the last word on this to Professor David Austin.

“We were literally just talking about South Africa’s role in the International Court of Justice [charging Israel with genocide in Gaza]… and how important that had been in terms of just trying to raise the question of another voice on the world stage, [taking] the side of Palestinians… and what that might mean for a new resurgence in the kind of global solidarity.”

“As we were talking about that, a protest went by that we eventually joined. There were folks carrying a Palestinian flag, and the Irish Republic flag, and the South African flag. And what I would describe, you know, as a flag representing Indigenous peoples.”

“Just seeing those flags alongside each other was heartening. It was nice to see that. […] This is where the tendency is shifting towards, precisely at this moment.”

“So I think we are in a moment.”