Caveat: There is a reason I’ve largely avoided the Italian crime thriller/poliziotteschi genre all my life. That’s what Tele-Italia aired on Montréal’s defunct ethnic TV channel, along with La Piovra mafia series and commedia sexy all’italiana (Edwige Fenech, Banfi or Pierino vehicles). The ones found in the local video stores’ Italian section – as many in the diaspora preferred them over art films. My mother used to call the station to complain about the violence and request Totò comedies for her daughters.

Confronting my aversion to machoistic crap, I embarked on this testosterone-laden challenge of surveying the poliziotteschi for Montréal Serai, perusing all my Italian cinema books, only to find nary a section or mention of these films or directors. Niente. I came to the realization that I was a snob.

Trigger warnings: graphic sexual violence, misogyny

Vigilante films and the poliziottesco genre

The word vigilante stems from Latin. In Italian, vigilare means “to watch over” like a guard (vigile del corpo for bodyguard, vigile del fuoco for fireman, vigile urbano for traffic police). Critics have generally regarded vigilante films as exploitation genre, cult, B movies or of lower quality – except when they involve great actors or when their soundtrack is better than the film.

A vigilante film is an umbrella label co-existing in a variety of genres and subgenres where the protagonist has been wronged, and after a series of humiliations, sets out on a journey to exact his vengeance. The genres include westerns and, in the Italian case, spaghetti westerns. Their directors and writers reinvented themselves in the poliziotteschi or Italian crime thrillers. Vigilante films can subsume any genre such as gialli/horror/splatter, commedia all’italiana, film noir, zombie, musicals, dystopian sci-fi, grindhouse, blaxploitation, US Vietnam vet or biker action flicks, and sexploitation.

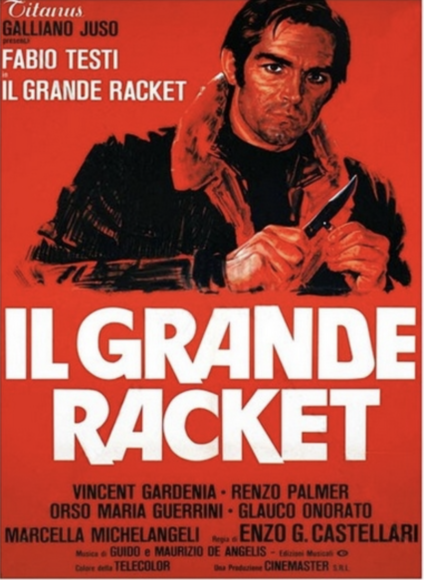

The birth of the poliziotteschi (poliziotti for coppers, and teschi reminiscent of skulls) came in the early 1970s, when westerns waned in popularity in America as well in Italy. Spaghetti western directors and writers, who originally started their careers in peplum (“sword-and-sandal” historical epics) films, began to migrate to the poliziotteschi or Italian crime thrillers. The masters of poliziotteschi were Fernando Di Leo, Umberto Lenzi and Enzo G. Castellari. The latter’s father, Marino Girolami, directed poliziotteschi films such as Violent Rome (1975) and Special Cop in Action (1976), while his uncle, Romolo Guerreri, directed Detective Belli (1969), Police serve the citizens? (1973), City under Siege (1974), and Young, Violent, Dangerous (1976).

Bullitt (Yates, 1968) with Steve McQueen, Dirty Harry (Siegal, 1971) and Serpico (Lumet, 1973) are often cited by American critics, who inaccurately claim that poliziotteschi are derivatives of American films. Such claims consider them inspirations for the Italian films’ crime in urban-decay landscapes, and for car chases. In fact, Italian crime films predate Clint Eastwood’s Harry character and the others. Also, to say that the notoriety of The Godfather (Coppola, 1972) made gangster films popular is too facile, when Italy had urban gangs and mafie in situ.

A turbulent history

In reality, Italy itself was already living through a turbulent period in the late sixties and seventies. The kidnappings of wealthy families’ children in the early 1970s was the main reason why families like Berlusconi’s were hiring former mafia henchman, and why others like Bruni-Tedeschi’s were leaving Italy for Paris.

Bank robberies, kidnappings for ransom, and political terrorism were the order of the day in the “years of lead” decade. Criminal cells were financing their operations through crime, especially the purchase of guns used for their robberies and kidnappings. Red Brigades interacted with and even converted some Mala (a northern gang) criminals in jail, while “black” (i.e., neo-fascist) terrorists collaborated and overlapped with both secret services and underworld gangs like la Banda della Magliana in Rome. (The latter’s penchant for urinating on enemies began to turn up in the poliziotteschi films.)

Italy’s civic and political culture of the time is very much reflected in these movies. The law is impotent. Institutions don’t work or are invisible. Judges and police are corrupt as in La Polizia é marcia, literally The Police Are Rotten – also known as Shoot First, Die Later (Di Leo, 1974). The state acts against the honest citizen and cannot be trusted. This is seen in these films in the theme of state terrorism, with politicians, secret service, and police collaborating with the mafia or neo-fascist terrorist aligned gangs.

This is especially true of the few poliziotteschi films set in the south, where distrust of institutions was already deeply ingrained. But it was also the case with the majority of the films set in urban milieus of the north. When police and institutions are not corrupt and complicit, citizens are helpless and hapless. La Polizia ha le mani legate literally means that democratic institutions “have their hands tied” in Killer Cop (Ercoli, 1975) and cannot keep repeat offenders off the streets. The Italian title of Lenzi’s Almost Human (1974) is Milano Odia: la polizia non puo sparare; literally, “the police can’t shoot back.” In all of these films, the police cover up their failures with the help of the media and the use of public relations. From quotidian purse snatchings and gangs (la Mala in the North and the mafia in the south) to foreign organized criminals like le Milieu from Marseilles (The Big Racket, 1976) or those from New York (La Mala Ordina / The Italian Connection,1972), these films reflected the concerns, conflicts and realities of life in the Italy of the 1970s.

Two films by Carlo Lizzani are considered to be precursors to the genre: Wake up and Die / Svegliati e uccidi (1966), based on the machine-gun bank robber Luciano Lutring, and his other thriller, The Violet Four (Banditi in Milano, 1968). Other poliziotteschi precursors include the film noir, Un detective / Detective Belli (Romolo Guerrieri, 1969), and Confessions of a Police Captain (1971, Damiano Damiani). Combining the elements of heist, terrorism, gangsterism and criminality, films like Execution Squad (Steno/Stefano Vanzina, 1972), Violent Professionals (Milano Trema, Sergio Martino, 1973) and High Crime (Enzo G. Castellari, 1973) especially cemented the genre’s popularity and are considered the first poliziotteschi. Franco Nero was the most common face of the vigilante film, whether in the spaghetti westerns Django (Sergio Corbucci, 1966) or Keoma (Castellari, 1976) or the poliziotteschi High Crime (Castellari, 1973), Street Law (Castellari, 1974).

The poliziotteschi genre is often peopled with protagonists like policemen, especially former or rogue policemen as in Execution Squad, Violent Professionals, and Double Game (Carlo Ausino, 1977). But even more common in the genre is the average citizen as vigilante, be it the engineer in Street Law / Il Cittadino si ribella (The Citizen Rebels) or the motorbike mechanic in Kidnap Syndicate (Di Leo, 1975). The titles paint the premise. Take Umberto Lenzi’s Manhunt in the City (1975), originally titled L’uomo della strada fa giustizia (Man from the Streets Makes Justice), while his Syndicate Sadists (1975) is titled Il giustiziere sfida la città (The Executioner Challenges the City). This film features Tomas Milian as a man who takes revenge on crime families for his friend’s murder. High Crime’s original Italian title translates to Police Incriminate and the Law Absolves, clearly putting the fault of lawlessness on the judiciary. Roberto Infascelli’s The Great Kidnapping (1973), whose Italian title is La Polizia sta a guardare (The Police Look On), conveys Italians’ frustration with the impassivity of the police. The Italian title for Kidnap (Faga, 1974) is Fatevi vivi, la polizia non interverrà; literally, “Come out because the police won’t intervene.”

Elements in the genre’s formula

After the (male) victim goes through the wringer of attrition and humiliation in some aspect of his life, the vigilante emerges. If the vigilante’s family member was kidnapped or killed, especially a child, this was considered the most egregious crime of all – thus vigilantism was the most righteous reason of all, and its violence righteous. Such a plot is seen in Kidnap Syndicate (Di Leo, 1975) when the working-class mechanic father searches for answers on his son’s accidental kidnapping, with revenge as the poor man’s equity, or Manhunt in the City (Lenzi, 1975), where the vigilante is specifically understood to be a good man. Even atoned criminals are worthy of sympathy when they are avenging wives or children. Big Guns / Tony Arzenta (Duccio Tessari, 1973) features Alain Delon as a mafia hitman who wants out of the crime life. When his bosses attempt to assassinate him with a car bomb but accidentally kill his wife and child, his revenge story begins. In Napoli Serenata Calibro 9 (Brescia, 1978), Mario Merola, a traditional Neapolitan singer turned actor in cheesy melodramas, plays a camorrista who becomes a vigilante when his son is killed while celebrating his First Communion.

One of the best poliziotteschi films focused on an average citizen as vigilante is Castellari’s Street Law (Il Cittadino si ribella / The Citizen Rebels, 1974). It stars Franco Nero as engineer Carlo Antonelli, taken hostage during a bank robbery in Genoa. He later tries to figure out the identities of the robbers by going deep undercover and finding their identities after following small-time crooks to organized crime. The police drop the charges.

Despite resistance from his wife and friends, Carlo bases his quest for justice against the criminals on the manifesto he learned from his partisan father’s death: “If you want to be free, you must resist. If the laws are unjust, it is your duty to rebel.” The following dialogue between Carlo and his wife Barbara is illuminating as to the populist politics of the poliziotteschi:

Barbara: “No man has the right to take the law into his own hands.”

Carlo: “Tired of being a docile good citizen. The State owes us allegiance.”

Barbara: “Our fault. People get the kind of government we desire. What do you solve with a pistol?”

Carlo: “What do you get with a protest?”

Barbara: “I am not waiting around for an autopsy.”

The film ends with another citizen filing a police report after being robbed for the third time: “Tired of living in fear. Tired of your goddamn indifference.”

Music

The soundtracks to these films were worthy of their own praise and attention. Masters like Ennio Morricone, Luis Bacalov, Stelvio Cipriani and Armando Trovajoli all composed for the poliziotteschi. Guido and Maurizio de Angelis were friends of Franco Nero, and their songs “Goodbye My Friend” and “Drivin’ All Around” in Street Law’s soundtrack feature lyrics that explain the action that has elapsed onscreen.

Breasts and Bullets

Women in Italian vigilante films, particularly in poliziotteschi, are nearly always relegated to the role of eye candy. A typical role would be the bootless go-go dancer Nelly, played by Barbara Bouchet, known for her infamous scene in a bejewelled bikini in Fernando Di Leo’s Milano Calibro 9. Yet women face worse fates in these films than to be relegated to obligatory nudie shots: they are slapped around, punched, raped, hung naked, sodomized, or killed. In the latter case, their deaths may become the motivation for the vigilante’s revenge, such as in Tony Arzenta / Big Guns (Duccio Tessari, 1973). The giallo-poliziottesco hybrid, What Have They Done to Your Daughters? (Massimo Dallamano, 1974) unusually features a high-ranking woman (Giovanna Ralli) playing the role of a deputy prosecutor. Ralli is overseeing a case involving a teen prostitution ring and serial killer, but her powerful position can’t save her from her fate as a woman in a poliziottesco.

These films are almost always filmed fully within the male gaze, with a beautiful foreign actress as the central woman. This character will be wife, victim or treacherous villain, but never an equal sidekick or a vigilante who propels the story herself. Women are the mothers and wives to be saved in the patriarchal society built on the madonna/whore binary, and this is of course reflected in such a macho genre.

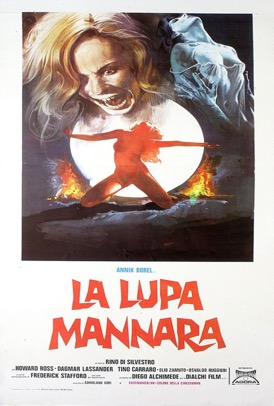

Even later vigilante films in the rape-and-revenge subgenre – which did allow for the woman to be the vigilante – remained replete with graphic sexual violence, misogyny and gore. Werewolf Woman (La lupa mannara, Rino Di Silvestro, 1976) is a sexploitation horror where lycanthropy is cured through sex. The main character is a child abuse survivor and rape survivor, but she undertakes the vigilante route for survival against a werewolf killer. Another rare woman vigilante in the exclusively female rape-and-revenge subgenre appears in the misogynistic nunsploitation film, The Last House on the Beach (Prosperi, 1978). Florinda Bolkan plays the nun who forsakes her vows and exacts vengeance on the gang rapists who victimized her and her friends. Written and directed by men, the male gaze galore remains. None of that “defend my family or my woman’s honour” stuff except when the woman’s revenge occurs within traditional patriarchal roles, as in Lady Dynamite (Vari, 1973, La Padrina). In this film, the wife of an Italian-American mobster takes revenge on a politician in Palermo after her husband is killed at their 10-year wedding anniversary party.

Aside from sexism, the films were rife with graphic violence tinged with sadism. This could be inflicted on persons of any gender. In Manhunt in the City (Lenzi, 1975), a transwoman is sodomized offscreen with a candle. The most violent of the poliziotteschi genre, Uomini si nasce poliziotti muore (Live like a Cop, Die like a Man, Deodato, 1976) featured a censored scene in which a drug addict’s eye was gouged out and stomped. Castration and a vat of acid were used as punishment in the censored Italo-Spanish co-production, Ricco the Mean Machine, whose alternate title was Cauldron of Death (Demicheli, 1973).

Fascist ideology associated with the poliziotteschi

Accusations of fascism have also long been associated with the poliziotteschi genre, especially the films that take pleasure in lingering on sadistic torture scenes. In the eyes of the Italian critics’ collective memory of fascism in the postwar period, violence was associated with the right wing.

Poliziotteschi directors and screenwriters like Umberto Lenzi, Sergio, and screenwriter Dardano Sacchetti have categorically refuted the fascist label. Carlo Lizzani, auteur film director with his seminal Violent Four/Banditi di Milano, was a partisan in the Resistance and member of Communist Party (PCI). Sergio Sollima, who directed Violent City (1970, co-written by Lina Wertmüller) and Revolver (1973), was also an anti-fascist partisan. Sergio Corbucci definitely wove anti-fascism messages into his vigilante spaghetti westerns such as Django (1966).

Umberto Lenzi was an anarchist like many Tuscans. Lenzi’s daughter said the poliziotteschi fascist criticisms came from “the hypocritical critics on the left,” and that in fact he was particularly interested in the Spanish Civil War. Lenzi in his own words has repeatedly refuted such charges:

Critics accused us of propagating a right-wing ideology because our policemen were violent. In reality, those were years when the banks did not have armored doors, the criminals broke in and started shooting: at the cinema theatre, people exorcised their psychosis. Today, thanks to directors like Tarantino, we are appreciated again (…) (Umberto Lenzi in La Repubblica interview, 2004)

What fascist? I was and remained an anarchist and as such I explored the world of cinema. So much so that then I switched to crime and horror. (Lenzi)

Actually, the political tension of the late sixties and seventies were affixed as an afterthought in the majority of these films’ narration, with some exceptions.

It would be an understatement to say that Morando Morandini, film critic of the traditionally liberal Milanese newspaper Il Giorno, wasn’t a fan of this genre. He panned and labelled many poliziotteschi as fascistic. His scathing review of Enzo G. Castellari’s The Big Racket (1976) – a film that mocks its supermarket thieves as a parody of far-left terrorists – is instructive as to this critical viewpoint:

It is fascist because, by combining the stereotype of the solitary executioner with that of the policeman rendered powerless in the exercise of his duty by the rules of the rule of law […], he supports the reactionary ideology according to which crime is not fought by applying the laws, but by contrasting violence with violence according to the rule of the taglione (knifings): tooth for tooth, killing by killing.

Castellari’s response was equally telling:

They call me a fascist. This is a fascist movie. I’m not interested in politics. And I didn’t understand why they called me fascist. I explain. But if bad guys are killing me and burning my house, nobody defends me and I defend myself; if that means to be a fascist, then I am a fascist. (Enzo Castellari, smiling, in an interview with Mike Malloy discussing Street Law, in the documentary Eurocrime! The Italian Cop and Gangster Films That Ruled the ’70s (Mike Malloy, 2012))

Dardano Sacchetti claimed to “destroy poliziottesco from the inside” and purge what he viewed as its fascistic tropes, by writing parodies. Tomas Milian’s ER Monezza (Trash Can) character derived from Milian’s earlier macho character Nico Giraldi. Franco Franchi of the Ciccio e Franco Sicilian comedy duo also parodies Death Wish (Winner, 1974) in The Noonday Executioner (Il Giustiere del Mezzogiorno, Amendola, 1975).

Finally, “going back to America” as subject and location in films like New York or San Francisco was a conscious effort for the Italians, to simultaneously reclaim something and return to the source in echoing Bullitt and Dirty Harry. One such film was Day of the Cobra (Castellari, 1980). Italian scriptwriters and directors fiercely contended that they were taking back Italian tropes that they had first developed in spaghetti westerns and early poliziotteschi. But they also began to move into the post- apocalyptic future in their US-themed action films. The futuristic sci-fi vigilante films 1990: Bronx Warriors (Castellari, 1982) and Escape from the Bronx / Warrior 2 / Fuga del Bronx (Castellari, 1983) were clearly influenced by Mad Max (Miller, 1979), The Exterminator (Glickenhaus, 1980), and Escape from New York (Carpenter, 1981).

The vigilante subgenre sprouted from a multitude of genres that spawned many more. As universal as the themes of revenge and violence may be, Italians seem to have latched on to it as subject matter as fiercely as the grip of a poliziotteschi stuntman on the roof of an Alfa Romeo in a death-defying car chase. This can be attributed to many factors: the political past, holes in the fabric of civil society, and the all-important cultural presence of family. It is a country and a cinema in which virtue and vice are intricately intertwined.

A poliziotteschi playlist:

Ennio Morricone (Investigation of a Citizen Above Suspicion, Revolver, Almost Human / Milano Odio: La Polizia non puo sparare, Last Stop on the Night Train)

Guido and Maurizio de Angelis (Goodbye My Friend and Drivin’ All Around in Street Law, Milano Trema, The Big Racket)

Luis Bacalov (Preludio in Milano Calibro 9, Il Boss, Mister Scarface / Padroni della città)

Stelvio Cipriani (La polizia sta a guardare from The Great Kidnappers, La polizia ha le mani legati. What have they done to your daughters?, Rabid Dogs, Colt 38, Mark the Narc series )

Riz Ortolani (Confessions of a Police Captain)

Piero Piccioni (Kidnap or Fatevi vivi la polizia non interverrà, 1974)

Armando Trovajoli (Di Leo’s La Mala Ordina / Italian Connection / Manhunt in the City, 1972)

Bruno Nicolai (L’uomo della strada from Lenzi’s L’uomo della strada fa giustizia/ The Manhunt, Manhunt in the City, 1975)

(1) To cite a few examples from recent Italian Superhero movies:

The tagline for the Italian Superhero film, Copperman (Eros Puglielli, 2019), within each of us contains a superhero, has an autistic Anselmo turning into a rollerblading superhero in a copper-welded costume as a metaphor for disability / superabilities.

Sleek and graphic, They call me Jeeg (Gabriele Mainetti, 2015) is based on a Japanese animated series with elements found in American comics and even poliziotteschi tropes, including misogyny with non-consensual sex and a transwoman. The title harkens back to They call me Trinity (Barboni, 1970), the spaghetti western parody with Terence Hill and Bud Spencer, while Steel Jeeg was a Japanese children’s animation series shown in Italy in the 1970s. Misanthropic loner Enzo by day, Jeeg becomes a social media celebrity in spite of himself when YouTube footage of Jeeg dressed like a black bloc antifa ripping ATMs from the wall goes viral.

The exceptions in the ideological outliers often include exposing the fascistic elements of society. Stefano Vanzina/Steno’s Execution Squad had a hard time being produced so the screenwriter directed the film himself. The stories were ripped from the headlines : Il Golpe Borghese coup with secret service involved in state terrorism was part of the story in Execution Squad. Piazza della Loggia bombing was alluded to Dallemano’s and Infascelli’s films shot in Brescia. The Circeo massacre, neo-fascist boys from “ good families” Roman bourgeoisie raped and murdered women which became a watershed event , inspired several poliziotteschi soon after.