SUICIDAL IDEALISM

Mark Silverman

We all have the strength

to endure the misfortunes of others.

Le Rochefoucauld

Nazareth. Halfway to somewhere, between the bigger places like

Syracuse and Binghamton, Buffalo and New York, maybe Washington and Ottawa.

A flat city. Centrally isolated at a bend in the interstate, surrounded by green

hills where dairy farming has been the major occupation since Indians were driven

off and the land parceled out to veterans of the war against England. Groups

of faded frame houses spread across the plain, bounded by the river and highway

to the east, shopping centers north and south. Some low-end factory work survives

since Smith Corona ran off to Mexico, and Nazareth College always provides some

jobs, but at the core, downtown lies withering.

One

late afternoon, on Route 218, a shadow engulfed the cars and everybody eased

up on the gas. They pulled onto the shoulder and got out to gaze at an enormous

balloon creature swimming in the air, looming over traffic in an orange and

white jumpsuit, rouged cheeks with a pencil thin mustache, puffy chef's cap

pulled to one side over flaming hair. The creature beckoned to the people below

with an outstretched arm, - c'mon and have a Boston creme or a honey dip or

a double chocolate or a cranberry nut muffin or maybe some fried holes. And

a cup or two of fabulous brew compliments of Mr. Donut. The blimp in captivity

had arrived.

One

late afternoon, on Route 218, a shadow engulfed the cars and everybody eased

up on the gas. They pulled onto the shoulder and got out to gaze at an enormous

balloon creature swimming in the air, looming over traffic in an orange and

white jumpsuit, rouged cheeks with a pencil thin mustache, puffy chef's cap

pulled to one side over flaming hair. The creature beckoned to the people below

with an outstretched arm, - c'mon and have a Boston creme or a honey dip or

a double chocolate or a cranberry nut muffin or maybe some fried holes. And

a cup or two of fabulous brew compliments of Mr. Donut. The blimp in captivity

had arrived.

Buffeted by the seasons, the huge balloon flew year round.

In winter shivering and sniffling on frigid mornings, and when the weather reversed,

gasping on the torrid afternoons. But at night, some nights, when the moon lit

the sky and the scrambled stars leaned overhead, and traffic out front slowed

to occasional pickup trucks threading their boozy way home, the donut-man danced

out back in the parking lot, a hip-swinger grinding in place with cape blowing

in the breeze, a single spotlight in back, as if the whole world might come

to see a monster fandango.

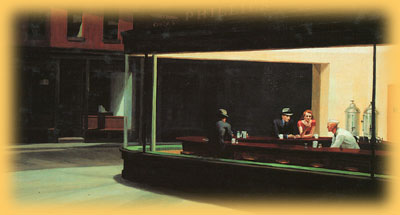

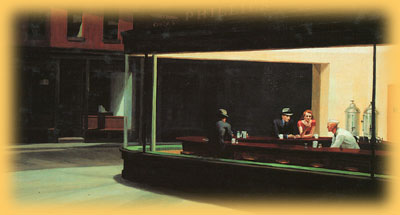

Just to be safe, he always saluted the balloon when he pulled

up to Mr. Donut. Today he sat in a window booth, watching a smile slowdance

across the girl's face, Lucy's face. She was almost fifteen, conscious of her

power, a young cheetah in baggy pants and T-shirt painted with a gorgeous marijuana

leaf.

He

stared at the blue valleys under her eyes, wondering why she slathered on such

makeup despite perfect skin. Her dark hair spun into a long ponytail, the sides

shaved bald all the way up. She'd triple-studded her ears and pierced her nose,

lips, tongue, belly button, maybe more, tattooed her arms and ankles, and sometimes,

he glimpsed the pink rose etched on her chest.

He

stared at the blue valleys under her eyes, wondering why she slathered on such

makeup despite perfect skin. Her dark hair spun into a long ponytail, the sides

shaved bald all the way up. She'd triple-studded her ears and pierced her nose,

lips, tongue, belly button, maybe more, tattooed her arms and ankles, and sometimes,

he glimpsed the pink rose etched on her chest.

"So your mom, she rang at one thirty in the morning. Said

you were supposed to be home by ten." He stopped to split his country medley

muffin, tasting the still-warm carroty goo. He looked at the girl, knowing if

he pushed too hard she'd dash. Don't think too much.

Lucy sipped soda through a bent straw. "Uh-huh."

The coffee mug under his beard felt good, moist heat drifting

in. "What's it all . . ?" But Lucy yawned, "Don't ask."

She sat up and rolled her shoulders and he tried to keep his eyes on her face

since he knew she wanted him to watch her undulating breasts.

A door opened somewhere and now her words came fast. "I

need to talk about this dream last night. These nazis came to my door, they

came inside the house, arranging the furniture, seemed like hours. Then they

had a whole line of people marching like zombies or something. So am I a psycho-bitch?"

"Don't ask me. It's your dream."

In

August Lucy and a bunch of tough girls from Nazareth -- stoned out of their

minds -- borrowed somebody's car and drove to the Woodstock Festival near Rome

where they crashed the party, slipping under the fence with cases of beer for

the people who paid. If one of those girls delivered a baby, maybe there would

be a prize from the promoters, like free tickets in 2019.

In

August Lucy and a bunch of tough girls from Nazareth -- stoned out of their

minds -- borrowed somebody's car and drove to the Woodstock Festival near Rome

where they crashed the party, slipping under the fence with cases of beer for

the people who paid. If one of those girls delivered a baby, maybe there would

be a prize from the promoters, like free tickets in 2019.

"C'mon Luce, you don't need another PINS, not with Probation

already on your case. Remember how pissed you were when Judge Murdock bundled

you off to foster care?" The growl of the trucks outside mingled with a

Garth Brooks song drifting from the counter. He glanced out the window. A chunky

blond woman with two small children got out of a battered Oldsmobile. The little

girl clutched her Barbie and the boy cradled one of those pump water guns.

Lucy stretched her legs under the table brushing his knees.

"Like maybe I'll find myself a pimp and get it on with him and try heroin

and catch his AIDS and be dead meat by the time I'm eighteen. That all right

with you?" She curled her lips into a smile.

He watched the blond woman stumble into the next booth with

her brood. The little girl spilt juice and mama grabbed a handful of napkins.

He was thinking maybe his job would be easier if he worked with the young ones

instead of teens. "Hel-lo. Can we leave now?"

Lucy had enough for today. So bored. But he loved the way she

moved around the ring, on her toes, ready to fight. If she knew he cared, she'd've

played him like a steel guitar. In the movies a killer laughs in the face of

the ordinary guy who has the drop on him, 'You'll never pull that damn trigger,

never, cause you're a suck-ker.'

Her hour wasn't up, but he would take her back to school. Faces

changed, sometimes more zits, sometimes less. The boys were easier, younger,

surlier, always immature. Still, he got the same message either way. Enough

of this therapy crap! He had stuck with this job and wasn't sure why he put

up with the weird parents and the zero-tolerance school and old Judge Murdock.

But maybe these angry, foul-mouthed kids had something he needed. Maybe he liked

working the faultline between the generations.

Two days later he got the news bulletin on his answering machine.

A call from the high school, from the pay phone out front, where the roar of

the buses couldn't drown the social worker's sobs. "Oh god! They just took

Lucy to Nazareth Memorial . . . popped a little white pill in study hall and

. . . someone found her rolling in the hall . . . convulsions or a seizure.

Looks real bad."

At the hospital, he found her mother dozing on a fake leather

sofa in the ER waiting room. She had her legs pulled up beneath a red and white

polka dot skirt, tight black sweater on top. She didn't look the part of the

mother, more like an older sister, with the same jutting chin and broad nose,

and Lucy's bottomless dark eyes.

He exhaled slowly as he watched her twitch. Yeah, the woman

needed help. But he knew all about the world-saving fantasy, that urge to jump

into the pit and pull people out. He would fantasize about fresh air and decent

food, but dared not mention the idea of bringing them home.

She sneezed and opened her eyes. "They called me at the

motel, and when I got here they already pumped her. Don't know what the stuff

was, maybe amfamine."

Amphetamine.

He wanted more. "Have they let you see Lucy?" Her eyes filled, "Yeah,

they brought me right in." She got up to smooth her skirt and fish for

a cigarette. "Luce could hardly talk, like a baby again and so scared,

like the time that car hit her."

Amphetamine.

He wanted more. "Have they let you see Lucy?" Her eyes filled, "Yeah,

they brought me right in." She got up to smooth her skirt and fish for

a cigarette. "Luce could hardly talk, like a baby again and so scared,

like the time that car hit her."

He glanced at he machines. "Want coffee?"

They waited outside where she could smoke, just beyond the

automatic doors. He sipped some awful brew.

"When they woke her up they said she's okay . . . wouldn't

say what that pill was or who . . . Nurse said the police are sure to ask."

She stared at the darkening sky. "Why won't they let me take her home?"

On cue, a nurse came outside and said it might be an overnight.

Lucy had been taken from the ER up to 3C, the Psych Unit.

She wiped her face with the back of her hand, smearing her

makeup. "Help me get my baby."

Baby Lucy. The woman wore tinted glasses, of course. The real

Lucy made a habit of teasing the cops on Main Street, a can of beer in her hand

-- just to show her friends. Anyway, he knew they wouldn't surrender Lucy, not

that night anyway.

He smiled at the mother, noticing the swelling under the eyes,

the small lines spreading over her face, the look. Maybe she could pass for

young in the bars, but up close, even in faint daylight, it didn't work anymore.

Not yet thirty, but too many rough men and too much alcohol and smoke. Seemed

like the parents of his kids all traveled the same road. Most were still stuck

back in their own teens.

He touched her shoulder, "Hey look, you're beat and your

son's back home wondering where you could be. Let these folks put Lucy up for

the night and we'll spring her tomorrow. I promise."

"But they might have to send her to Syracuse, up to Hutchings,

because . . . " She spoke carefully, her eyes wide, "they told me

Lucy has suicidal idealism."

THE END

Voice Your Opinion

- Back to

the Table of Contents - HOME

One

late afternoon, on Route 218, a shadow engulfed the cars and everybody eased

up on the gas. They pulled onto the shoulder and got out to gaze at an enormous

balloon creature swimming in the air, looming over traffic in an orange and

white jumpsuit, rouged cheeks with a pencil thin mustache, puffy chef's cap

pulled to one side over flaming hair. The creature beckoned to the people below

with an outstretched arm, - c'mon and have a Boston creme or a honey dip or

a double chocolate or a cranberry nut muffin or maybe some fried holes. And

a cup or two of fabulous brew compliments of Mr. Donut. The blimp in captivity

had arrived.

One

late afternoon, on Route 218, a shadow engulfed the cars and everybody eased

up on the gas. They pulled onto the shoulder and got out to gaze at an enormous

balloon creature swimming in the air, looming over traffic in an orange and

white jumpsuit, rouged cheeks with a pencil thin mustache, puffy chef's cap

pulled to one side over flaming hair. The creature beckoned to the people below

with an outstretched arm, - c'mon and have a Boston creme or a honey dip or

a double chocolate or a cranberry nut muffin or maybe some fried holes. And

a cup or two of fabulous brew compliments of Mr. Donut. The blimp in captivity

had arrived. He

stared at the blue valleys under her eyes, wondering why she slathered on such

makeup despite perfect skin. Her dark hair spun into a long ponytail, the sides

shaved bald all the way up. She'd triple-studded her ears and pierced her nose,

lips, tongue, belly button, maybe more, tattooed her arms and ankles, and sometimes,

he glimpsed the pink rose etched on her chest.

He

stared at the blue valleys under her eyes, wondering why she slathered on such

makeup despite perfect skin. Her dark hair spun into a long ponytail, the sides

shaved bald all the way up. She'd triple-studded her ears and pierced her nose,

lips, tongue, belly button, maybe more, tattooed her arms and ankles, and sometimes,

he glimpsed the pink rose etched on her chest. In

August Lucy and a bunch of tough girls from Nazareth -- stoned out of their

minds -- borrowed somebody's car and drove to the Woodstock Festival near Rome

where they crashed the party, slipping under the fence with cases of beer for

the people who paid. If one of those girls delivered a baby, maybe there would

be a prize from the promoters, like free tickets in 2019.

In

August Lucy and a bunch of tough girls from Nazareth -- stoned out of their

minds -- borrowed somebody's car and drove to the Woodstock Festival near Rome

where they crashed the party, slipping under the fence with cases of beer for

the people who paid. If one of those girls delivered a baby, maybe there would

be a prize from the promoters, like free tickets in 2019. Amphetamine.

He wanted more. "Have they let you see Lucy?" Her eyes filled, "Yeah,

they brought me right in." She got up to smooth her skirt and fish for

a cigarette. "Luce could hardly talk, like a baby again and so scared,

like the time that car hit her."

Amphetamine.

He wanted more. "Have they let you see Lucy?" Her eyes filled, "Yeah,

they brought me right in." She got up to smooth her skirt and fish for

a cigarette. "Luce could hardly talk, like a baby again and so scared,

like the time that car hit her."