Maya Khankhoje’s dream has been to enter the Dreamtime of the Australian Aborigines. This film afforded her a virtual entry into this dimension.

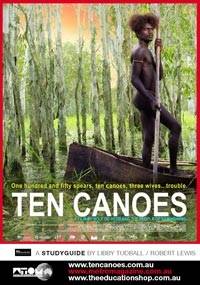

TEN CANOES, 2006, 90 minutes, Australia. Available in DVD. By Rolf de Heer and the people of Ramingining. Starring Richard Birrinbirrin, David Gulpili and Jamie Gulpili.

|

The story of humanity is woven from the common strands of love, longing, loss, jealousy, betrayal and greed. Survival, of course, is the main thread running throughout the narrative of humanity. Ten Canoes is the story of what can happen when you covet your neighbour’s woman, or more precisely here, your elder brother’s youngest wife. It is also an attempt at a realistic reconstruction of the lives of Australian Aborigines before the White Man stepped on this vast continent. David Gulpili narrates the story in an English voice-over while the rest of the actors, most of them non professionals, perform the other story within a story in the Ganalbingu language of Australia.

In theme and intent, Ten Canoes is reminiscent of Atanarjuat, (see www.montrealserai.com/2002_Volume15/15_3/Article_6A.htm) the first Canadian film performed entirely by Inuits in the Inuktitut language. Both films deal with the forbidden love of a younger man for his older brother’s/best friend’s woman. In both there is complete nudity, shocking in the cold Canadian north, completely natural in the warm Australian marshlands. In both films there is murder and tribal retribution with some sorcery thrown in. The photography in both is stunning. Both Atanarjuat and Ten Canoes were received with critical acclaim, although not all Australian viewers have been amused, some finding the film much too slow. Others, however, have praised it for “not being political, thank god!”, which for me is its weak point. And the women in the film are treated as mere possessions with no voice of their own, something difficult to imagine, even for mythical times, since in hunting and gathering societies, women’s economic contribution was essential for survival.

|

Director Rolf de Heer is supposed to have said “we need ten canoes” while trying to develop the plot for the film. Whether this comment is apocryphal or not is irrelevant, because the bark canoes built by the protagonists became the vehicle for the action. While the men are building their canoes to go goose-egg hunting, Minygululu, the leader of the hunting party, tells Dayindi, his young unmarried brother, an ancestral parable that transpired a thousand years ago, that is, once upon a time. In the mythical story the young man acts on his desires to get his elder brother’s third wife, with tragic consequences. In the present story, the young man pays heed to the morality tale and all is well, as good an argument as any in favor of the status quo, which surely pleased “apolitical” white Australian reviewers.

The climax of the film is a death scene in which the sorcerer and other members of the community perform a death dance to help the dying man reconnect with his ancestor spirits. According to the myth of creation of the Yolngu culture, we were all once upon a time a tiny fish in a waterhole. Father then places us inside Mother so that we can be born. At death, we once again become a tiny fish in a waterhole. The death dance guides us back to our original waterhole.

The making of the film was interesting. A decision was made by the director and his crew not to show inter-tribal warfare and the plot was jointly developed by the whole film crew. Scenes from the mythical past are depicted in black and white stills taken in the thirties by anthropologist Donald Thompson, who studied the Yolngu culture. The colour sequences, depicting the present, were shot in the Arafura Swamps to the north east of Australia. There are breath-taking aerial views of this region which is home to the largest crocodile population in the world as well as a large variety of flora and fauna. The logistics for the film crew proved to be very challenging. Aside from the dangers of the natural habitat, there were the challenges of interpreting from various Aboriginal languages into other languages and then English. The film, however, is seamless, thanks, in part, to the poetic and humorous voiceover.

|

Let us hear the narrator’s voice:

“It’s a good story, this story I’m gonna be tellin’ you ‘bout the ancient ones….Ahh, you gotta see this story of mine cause it’ll make you laugh, even if you’re not a blackfella. Might cry a bit too eh? But then you laugh some more…cause this story is a big true story of my people. True thing.”