Mirella Bontempo is a Montreal writer and film enthusiast.

Part 1 - Given the size of this article it will be published in 2 pieces. Part 1 in Vol 20 No 1 and Part 2 in Vol 20 No 2.

Dedicated to:

To my maternal great grandfather D. Di T. and his sons who built the CN railway tracks in the Mile End area and Ontario corridor (sleeping in carts), also returned to Italy in 1933 while his sons settled in Belleville. In WW2 Italy, he was able to intervene at a hospital when his granddaughter was amputated simply because he spoke English to the British doctors. He was able to keep contact with his sons in Canada during the war because he was reunited with a Canadian soldier who used to sit on his lap in Belleville. To my paternal great grandfather F. M. who was a foreman for Cadbury factory in Montreal during the Depression, who fed his out of work paesani in Montreal’s first Little Italy (St-Timotée and St-Andre; now the Gay Village) in their boarding-house. He arrived at the age of 16 and became a Canadian citizen in 1904. He also left in 1932 after his fortunes were made when his daughter was to get married. The British allies found his Canadian passport in the river since it was dangerous to keep it under German occupation. He returned to Canada in 1948, just for three years, working as a night watchman at 67 years old purely to sponsor his family. Only to have their son-in-laws, daughters, son and grandchildren re-immigrate in 1950s. Now tell me to go back to Italy when my ancestors built this country’s infrastructure. |

The Italian Fruit Vendor

Ice a crem – sex banana ‘vive cent

Pea nut drtee cent sze glass.

Ah Lady! Sez ‘Talyman’s cheap

Tou no tink he will sell, and he vass.

….

At the southwestern corner of Adelaide and Yonge,

Where the Saxon falls sweet from the soft Latin tongue.W. A. Sherwood, The Canadian Magazine November 1895. 1

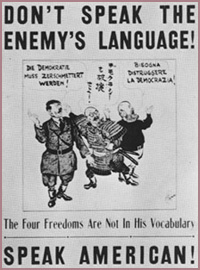

Most people never heard of Italophobia, which sounds like a hackneyed term coined in the age we used to have political correctness. Now that we’ve passed this PC threshold, it seems people are more at ease with disclosing their prejudices. It’s a lesser-known prejudice or pathology, say, than the traditional ones based on race, religion, gender or sexual orientation. As you’ll see, it is traditional. It’s not like you can easily accuse someone of being Italophobic or Italophobist. It doesn’t exactly roll off the tongue. Most Italians are probably oblivious to this term (hell, I only heard of it at university). The happy-go-lucky Italian archetypical jovial person couldn’t care or blame others of harbouring a chip on their shoulders, those angry anti-defamation types. But most wouldn’t deny they felt some antagonism at some time – it’s a feeling.

The term was coined by Robert Harney, from the Multicultural History Society of Ontario, in his seminal paper “Italophobia: an English-speaking malady?” (1985). Italophobia, according to Harney, stemmed from knife-wielding men in tights stereotypes first concocted in English literature starting from Chaucer and Shakespeare’s fascination with Renaissance Italy and where the myth building of Italian stock character took root.

|

“[The] English and North American image of Italians as fractious, fickle, preoccupied with intrigue, foppish, occasionally treacherous and always quick with the arma bianca - moved from Elizabethan stage to the English consciousness.” 2 Though evident are the critiques of Othello and Shylock, his characterizations of Blacks and Jews, society seems more compliant to accept the Bard’s Italian characters at face value. Swarthy meant to be based on skin’s complexion as blackness, Schwartzyness. 3 More stereotypes: fraticides, “dandies, seducers, fops and intriguers.” 4 To be fair, Shakespeare’s English characters do not fair well; that is, if he wrote those plays - the Marlowe conspiracy. Also responsible in contributing to these stereotypes emanated from Italy as well, melodramatic high art exports like Leoncavallo’s opera I Pagliacci where Canio, the clown, commits an honour killing of his wife Nedda whom he suspects of cheating.

The myths from literature were transposed to English-speaking lands where the myths of artists and political exiles were less a reality in lands which hosted mass immigration, made mostly of Italy’s peasantry, where organ grinders and fruit peddlers became the new archetypes for early Eyetalian émigrés. The assimilation of Italian words into English: Ruffian from the Neapolitan ruffiano as pimp, bordello, vendetta, stiletto and the various mafie, seem to be done with ease if “ linking the ethnic group with asocial behaviour and criminality ” but getting someone pronounce other Italian words, say Bruschetta, without some linguistic massacre - not so easy, eh? 5

Italian cuisine is a blessing and a curse, a double-edge stiletto if you will: much revered and so widespread that it is easily used in the personification of an object, dehumanising no matter how edible the object. Official Canadian governmental documents such as an immigration committee on illegal entrants in 1926 when a member asked, “Suppose somebody makes an application for say, Mr. Spaghetti to come into Canada; how do you know whether it is Mr. Spaghetti that came in or Mr. Vermicelli.” 6 The Immigration Act of 1919 (one of many acts affecting various ethnicities at various times with various dubious practices to restrict immigration such as the infamous head tax) stated, “No immigrant shall bring into Canada, any pistol, sheath knife, dagger, stiletto, or other offensive weapon that can be concealed upon the person.” 7 Harney notes the word stiletto is italicised and is the only foreign word in the sentence. I suppose yesterday’s specific pointy knife by any other name wouldn’t do, today we could replace sheath knife with Kirpan in the current unreasonable accommodations debate. To me, stiletto always meant pointy heels, but then again, my father was in the shoe business.

|

The history of immigration in Canada was primarily designed to select and restrict migrants on the basis of who could get acclimatized to our climate and our customs (Immigration Act of 1910 restricted immigration from hot climates rather than outright barring the dark-skinned – discontinued in the 1960s). British and American immigration appeared foremost on the list, and only after failing to attract Scandinavian immigration, Eastern European was regarded by Clifford Sifton, Laurier’s Minister of the Interior (1896-1905), as the best kind of immigrant for the peopling of the West; “I think that a stalwart peasant in a sheepskin coat, born to the soil, whose fathers have been farmers for ten generations, with a stout wife and a half-dozen children, is good quality.” 8 But “southern Italy was deliberately excluded [in the roster] because Sifton’s disdain for southern Europeans and their mythical inability to meet the challenges of prairie frontier life.” 9

Harney heavily presents some examples from Canadiana, mostly from Toronto the Good and Orange, about the same time the first wave of the Italian immigration began - the Other up close. The Italian Fruit Vendor prose I used to preface this article demonstrates native-speaking English’s rendition on how an Italian speaking English is supposed to sound like, which is not unlike to what we hear on today’s Canadian satire shows.

The condescension of the mandatory broken English demonstrates that the themes of a propensity for frivolity, for fondness for grandiloquence and inconsequence which formed part of the traditional Italophobia still were belittling when used apparently sympathetically. 10

|

He cites some more, this time from an American advertisement:

They are poor but happy, careless, light-hearted, impulsive, impetuous, affectionate, sanguine, emotional, languorous and generous. Pomp and circumstance dazzle them. Ribbons geegaws and bright colours enslave them. 11

Arbuckle Coffee, circa 1870

A Toronto editorial for The Globe Saturday Magazine 1910:

The multitude of little fruit stores that many Italians have here attained the summit of their hopes. Only to look into the cherry faces of the vendors of popcorn or peanuts who perambulate our streets…confirms this pleasing suspicion. 12

The United Church Record of Toronto referred to Italians’ “sunniness of nature and love of art and music” which could be interpreted as “insouciance and perhaps even laziness and social irresponsibility to the English-speaking host society.” 13

But what was so threatening about short simpletons? Fear arose when naiveté could potentially lead to deception and instinctual violence.

From the Presbyterian Record July 1910:

[Italians]“are physically strong...but low in mentality; they are warm-hearted, kind and grateful, but also hot-blooded and given to fighting and violent crimes… They present problems of overcrowding, ill health intemperance, Sabbath desecration, political impurity.14

There were also racial differences noted as in Fort William Daily Times Journal “reported that the Canadian Pacific Railway had promised a citizen’s committee that they would not hire ‘Black Italians’… reported that ‘White Italians’ Trevisani and Fruilan did not engaged in violent strike action.” 15 The major threat, besides low paid immigrants stealing jobs from the natives, was organized labour where Italians were actors. The irony is that Italians were simultaneously portrayed throughout the ages as being:

- politically unsophisticated due from their inherent illiterate ignorance.

- politically and civically indifferent due to economic opportunism (sold their soul for a pittance of a wage) or worse, indifference due to cowardice or omertà.

- and so politically sophisticated to been seen by the authorities as threatening agitators sowing foreign ideologies (be it communist, anarchist or fascist).

Even when they embraced homegrown federalism or espousing a party, which renders lip service to Multiculturalism, they become politically cumbersome and disposable. But that’s part and parcel of the immigrant experience.

Port Arthur Daily News of the same period exploited the fears:

The major concern is the circumstances that among the strikers are a majority of foreigners, chiefly Italians, who are reported to have to have prepared to meet opposition to their demands at the point of the knife, the national weapon of the dago… A community of British citizens should not have to submit to the obloquy of insult and armed defiance from a disorganized horde of ignorant and low-down mongreal (sic) swashbuckliers (sic) and peanut vendors.16

|

Even Canada’s Italian elite at the time, the middlemen supplying work and workers, promulgated the stereotypes between farmer and peasant, skilled and unskilled workers, northerner and southerner. The Royal Commission of 1904 reported one of their testimonies: “from north of Italy…from the Venetian province…are good men. They are picked men, and any railway company would be glad to have these men, because they are strong and even good looking.”17 A policy that was created explicitly for Italians was devised in 1959 from Ellen Fairclough, Canada’s first female cabinet minister, who wanted to curb the sponsored family condition for unskilled Southern Italians, on the premise the practice discriminated against the skilled labourers from Northern Italy. 18 She claimed family sponsorship backlogged the system. It didn’t go to well in her Italian constituency in Hamilton. The fact Italian immigration continued to grow from 12,000 in 1954 to 63,000 in 1959 proved the policy wasn’t going to work since “until the mid-1960 immigration from Italy continued to outstrip immigration from Great Britain for the third consecutive year.”19

But I challenged the title, that it is exclusive to English societies and widen the universal dimension of Italophobia probably outside Harney's initial scope. He does mention Quebec comparatively – how bourgeois women picked up Italian in salons and Quebec's mass protest in 1909 against Rome's mayor Ernesto Nathan who was English-born, Jewish and a freemason. But he contends, "It is fair to add that Italophobia in Latin Quebec never took a cutting edge as it did in English-Canada and United States." 20 Then adds the religious marked difference by a German-American Redemptorist Church adherer's comment "the spiritual betterment of these southern Italians is an impossible task…partly on account of the inborn indifference of this people." 21 Is it just an English-malady? Armed with various examples Latin and Teutonic cultures, past and recent, anyone can hold such feelings towards Italians. Like Irish and Jewish migrants before them with their own burdensome stereotypes, it would be logical that North America would target and see each successive mass migration as neo-invaders threatening even when the migrants used to be European but just different. And different is bad.

Recently, the much controversial survey commissioned by Leger and Leger Marketing on racism, entitled La grande enquete sur la tolerance au Quebec (January 19, 2007 – only on its French website) and ‘Reasonable Accommodation’ debate (it seems every decade, there’s some obsessive cultural preoccupation that doesn’t dare speak its name), where uninhibited Quebecois respondents declared frankly which peoples they had good or bad opinions of. In the top 6 incurring overall bad impression roster, after Arabs (50%), Jews (36%), Blacks (27 %), Latin American (17 %) and Asian (10%), Italians were included as the last group (5%). 22 A mere 5 % amongst Quebecois francophone in origin thought negatively of Italians while 7% non-francophones made up of other “cultural communities” (Quebec lingo for minorities) held a bad opinion of Italians. No other group was country-specific since all the above come from a variety of nations. No other European in origin (or Southern European) community that is significant in Quebec was mentioned. It could be also that Italians used to be significant in numbers in Canada in 1970; Italian usurped German as Canada’s third unofficial language and ethnic group at one million. In the 1986 Census of Canada Italian was second to German as the reported ethnic origin with the exception of Quebec and Ontario where Italian came in first.23 But in the heritage, mother tongue or home language section Italian figured first in the same census. 24 Chinese, in turn, recently usurped Italians, in rank and numbers. In Montreal alone, the Italian population is 250,000 – half that of Toronto’s Italian population.

Why the inclusion of Italians? Perhaps as a comparative measure traditional prejudices based on race and religion versus a white Latin group similar to that of a traditional Quebec (Latin language, white and Catholic which prompted intermarriages between the ethnicities). The fact that non-francophones made of Anglophone and other ethnic respondents (7%) closely mirror the 5% from de souche respondents reflects the term’s universality. This is the only category where all non-Francophones’ negative impression of the ethnic group in question superseded that of Francophones’. There’s Italophobia in a statistical measure. The conclusion is that also non-Francophones (i.e. those also coming from an ethnic or linguistic minority) are similarly prejudiced if we see how they view the Arab, Jewish, Black, Latinos, Asian communities, though, slightly less negative than how Francophones responded.

A poll commissioned by Canadian Institute of Public Opinion in 1946 “showed that 25 percent of those polled wished to keep Italians out of Canada” where wartime feelings might have been a factor. While a similar poll taken later in 1955 had 4.4% were accepting of immigration from the Mediterranean while 30% were more receptive to Northwestern Europeans aligned to Canada’s official immigration preferences as the time. 25 Some claim Italophobia in the general population could be traced at its historical opportunistic flip-flopping onto the winning side during the two world wars. But Italy’s mass immigration of the late 19th Century and the articles they inspired predate these 20th Century wars.

Historically, Quebec’s Italophobia also mirrors the negative stereotypes categorized by Harney in his study of English-literature. From street kids’ taunts that “les italiens pu du swing ” in 1950s, basically that Italians smell (swing is Quebecois joual for funk, B.O. reminiscent an American ethnic joke book from the 1970s shown to me as a kid which included jokes about Italian dental hygiene and sandblasting remedy for rotten teeth). Bruno Ramirez and Michael Del Balso’s book The Italians of Montreal:From Sojourning to Settlement:1900-1921 chronicles the documented sensationalism from La Presse. In an article entitled “Un foyer Infect,” the reporter describes the Italians on Roy Street as “ toute une colonie italienne dans une malpropreté et une promiscuité dangereuses.” 26 The media reported on knifings and duelling in downtown Montreal’s Windsor Station boarding house ghetto with “ruelle infecte où vivent des centaines d’Italiens de la classe miséreuse.” 27

The controversial rationale behind today’s reasonable accommodations harkens back to the same preoccupations from the early 20th Century: “contemporary observers to view it as some pathological manifestation of a cultural group to be unable to adapt to the mores and institutional imperatives of the hosting society.” 28 In such articles, La Presse manufactured in the “creation of cultural stereotypes” where “Italians were portrayed as hot-tempered, uncivilised in their manners, quick to take the law in their own hands, and when they did so they displayed sanguinary instincts.” 29 The reporters observed the macabre details while omitting that fights were amongst Italians themselves. There was no urge to cover the outlining discrimination immigrants faced because Italians weren’t their readers. Civic complaints troubled the Mayor H Laporte into writing to Prime Minister Laurier in 1904: “A sentiment pervades our citizens that these people who have been enticed to Montreal, may commit excesses, because we have not sufficient employment at the present to give them.”30

Many non-pure-laine children were discouraged from overcrowded French schools so education took place in La Difesa Church’s overcrowded basement that forced them to rent a building on St-Zotique. Some went to nearby St. Edward’s or Protestant English schools, and only one French school, Philippe (Filippo) Benizi, was available because it was created by a Florentine religious order in Little Italy in 1936. As the population in the English public (Catholic) school commission swelled in 1960s thanks to Italian children while French schools’ population dwindled, so did the linguistic anxiety – the original obsession par excellence. 31 Not for nuthin’, Italians instinctually mobilized in 1969 after Bill 63 was passed, and after the St-Leonard school commission in a predominately Italian municipality proposed to bar Italians from the English school system. 32 The St-Leonard Riot is described in the official high school Quebec History textbook as “a 16 hour orgy of violence” where chairs were flung and storefronts smashed.

To be continued in Vol 20 No 2.

*******

1 Harney, Robert. F. “ Italophobia: An English-speaking Malady?” Stud Emigrazione/Etudes Migrations, vol. 22 no. 77 1985: 6- 43; 14.

2 Ibid, 19

3 Ibid, 11

4 Ibid, 12

5 Ibid, 22

6 Ibid, 22 From Report of the Select Committee on Agriculture and Colonization (1929), p.69

7 Idem.

8 Knowles, Valerie Strangers at Our Gates: Canadian Immigration and Immigration Policy, 1540-1990.Toronto: Dundurn Press Ltd, 1992. p. 64.

9 Ibid, 65-66

10 Harney, 18

11 Ibid, 19

12 Idem

13 Idem

14 Ibid, 21

15 Ibid, 40-41

16 Ibid, 41

17 Del Balso, Michael and Ramirez, Bruno. The Italians of Montreal: From Sojourning to Settlement: 1900 - 1921. Montreal: Les editions du courant, 1980. p.7.

18 Knowles, 139

19 Knowles, 140

20 Harney, 18

21 Idem

22 La grande enquete sur la tolerance au Quebec, le 19 janvier 2007, pdf document, http://legermarketing.com/documents/spclm/070119fr.pdf

23 Augie Fleras and Jean Leonard Elliott Multiculturalism in Canada: The Challenge of Diversity. Scarbourough: Nelson Canada, 1992. p. 30.

24 Ibid, 150

25 Harney, 9

26 Del Balso and Ramirez, 6. See footnote 8 (La Presse March 3, 1905).

27 Idem

28 Idem

29 Ibid, pp. 6-7

30 Ibid, 12 see footnote 18.

31 Statistical information about Italian population in English schools: http://www2.marianopolis.edu/quebechistory/stats/italians.htm from ‘Pour finir avec un myth’, R. Gagnon, Bulletin d’histoire politique, 1997, pp 130-131.

32 Language laws chronology:

http://www2.marianopolis.edu/quebechistory/readings/langlaws.htm