Maria Worton is an Serai Editorial board member and local activist.

|

|---|

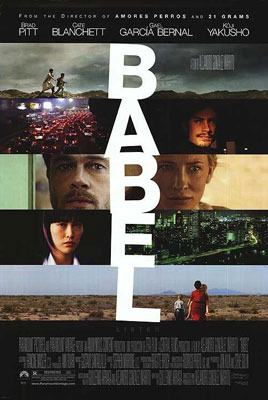

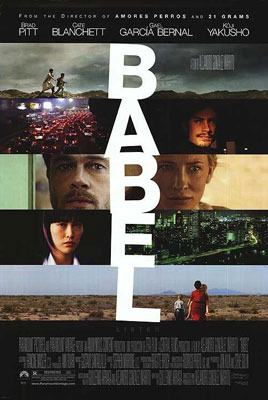

Babel is a good film but not a great film. It often gets 3 stars rather than 5. And I give it a 3 too. Why? Because Alejandro Gonzalez Iñárritu’s original intention seems to me to be relatively slight to begin with: “With Babel, I wanted to explore the contradiction between the impression that the world has become quite small due to all the communication tools which we have and the feeling that human beings are still incapable of expressing themselves and communicating amongst themselves on a fundamental level.” For those of us living in large, fast, crowded, multi-cultural cities, we know how small the world is and that, yes, fundamental communication can be difficult even without language and cultural barriers in a cell-phoned society. Sheer proximity, increased social acceleration and oil wars can also aggravate matters between people. In a film that lasts 2 hours and 20 minutes I’d argue Iñárritu explores his subject but then labors a relatively obvious point in a way that is less than convincing.

With the title being Babel, Inarritu reminds us of the tower of that name: the myth of which goes that a united humanity were building a tower to reach the heavens. But instead of worshipping the God that created them they were striving for their own prestige. God, not one to be ignored, rudely arrested the builders’ development by afflicting them with different languages and scattering them about the world.

Babel begins in Morocco with the purchase of a high powered rifle to ward off jackals. The rifle in the hands of two Moroccan children, sibling rivals (Said Tarchani and Boubker Ait El Caid) becomes the source of all woe. Out goat herding the younger of the two brothers aims at a distant coach to prove the rifle’s range and so doing accidentally shoots an American wife/mother (Cate Blanchett). The husband/father (Brad Pitt), by cell phone, informs the Mexican nanny (Adriana Barraza) back in the US that their return is delayed. With her son’s wedding to attend the Mexican nanny decides to cross the border with her two charges in tow. On their illegal re-entry to the US, the car is stopped at the border and her nephew, fearing arrest, tears off, en route stranding his aunt and the children in the desert.

|

|---|

Minaret of SamarraThe confusion of tongues by Gustave Doré |

Babel has something to say for showing people in dire circumstances panicking under the pressure to do the right thing. Then, given too little information, making credibly poor choices. And isn’t that just how life is? Babel also shows, in culturally disparate situations, loving people trying and failing to understand each other. A sophisticated soundtrack deftly plays with silence and muted noise to drive home altered emotional states and the deafness perhaps induced by panic. There are moving performances all round. All of this often lends an authenticity to the experiences we see. Everyday events such as these happen. Seemingly curious coincidences do occur and freak events unfold.

And everyday, as everyone knows, guns ruin lives in ways we don’t appear to anticipate. Why? Because people fail to communicate? Well yeees…but… isn’t that like saying people starve because they need to eat. It’s a simplification. Perhaps even a gross simplification. Dr. Phil type thinking. Though in fairness, Babel does take a broad view of communication: It hints that hunting is a past time for wealthy Tokyo urbanites trying to find their way in a contemporary wilderness that challenges intimacy. It hints at the official way America patrols its Mexican border violently even as it exploits a hidden economy of millions of Mexican workers. It hints that Mexico is a third world country on the southern border of the wealthiest nation in the world. It hints at the brutality of old, post-colonial societies such as Morocco. It shows the north/south divide wherein white middle class westerners are cushioned while the tragic fates of the Moroccan family and Mexican nanny would appear almost sealed from early on. It hints at and shows a lot of poor communication going on between people and people, and people and power. But can the nature of power and influence be simply reduced to a problem of communication? To what degree is communication a cause; to what degree an effect?

Well, to my mind, the film loses potential for emphasizing communication as a first cause of human misery. With this emphasis it then contrives a kind of closure: It does this on the back of an odd skein woven throughout that tells the Japanese tale of a deaf, Tokyo teenager, hurt, angry and acting out in search of solace through her sexuality a year after the suicide of her mother. Eventually she finds some peace of mind through an unclear, unlikely interlude involving a detective. The detective is tracing the rifle her father gave his Moroccan hunting guide as a token of gratitude, the same rifle used by the Moroccan boys. Following the interlude with the detective, the young woman is mystically reconciled with her estranged father. So much of the film is raw and explicit but this segment jars for being forced and transcendental.

Then in the film there’s the unrelenting nature of frenetic camera movement, fast cuts, extreme close-ups and a highly dynamic soundtrack. All of which, don’t get me wrong, conspire for some time to engage this susceptible viewer in a riveting emotional rollercoaster ride.

However, while it’s exciting to experience such a chaotic scramble of converging realities, the sustained intensity amounts to sensationalism. Until all this zipping about between continents feels to me, after nearly two hours, to border on redundancy. Until finally, its surfeit of sensationalism and outrageous plot contrivance disconnects me from Babel. Until I have nothing left to give for the lingering close up of Brad Pitt’s distraught features over the phone to his son. At which time I sit back and experience how the film manipulates and loses touch with its humanist impulses. Failing to deliver a greater, deeper sense of reality Babel becomes a lesser lesson in how violence of various kinds begets violence, with an implicit warning that you might think twice before leaving home.

Leaving the cinema, I feel ever so slightly numb, emotionally flung about, then tossed aside. I’m left wondering that if God had had more politics, cognitive psychology and environmental concern under his belt would he have treated those builders of Babel quite so harshly? Would he have listened to their point of view? Have Gods ever made very good listeners? I don’t know. What I do know is that power unchecked corrupts.

Babel touches upon important themes that badly warrant deeper treatment: the many ways this socio/political system compromises human relationships and promotes as it institutionalizes violent communication of varying intensities, to name one. Because isn’t this the first problem? Not communication. But the way people are treated institutionally by governments and corporations and are institutionally, at home,at work and at play, conditioned to think. Because, after all, don’t we, in fact, feel or think before we speak?