the good lent

orissa arend

Commentary

Orissa Arend is a mediator, psychotherapist, and community organizer in New Orleans. You can reach her at arendsaxer@aol.com.

In 2006, in New Orleans, St. Augustine's, one of the oldest African American churches, home of civil rights action and great jazz, a bastion of the city's history and culture, had to do battle to survive. A member of it's community, Orissa Arend, tells the curious tale.

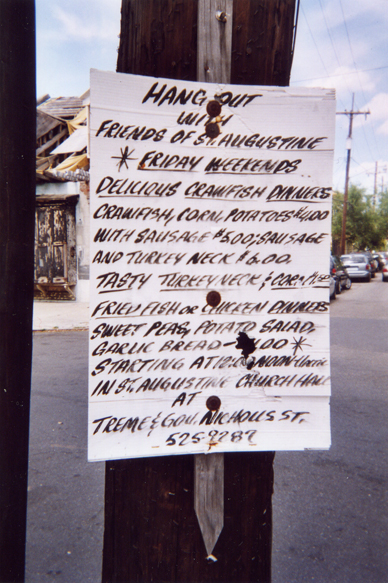

Inside St. Augustine's Church

|

Deep, deep into Lent in post-Katrina New Orleans everything seemed lost. Not only had our parish been declared dead; but now our church had been closed as well. People from the archdiocese came and got the Blessed Sacrament claiming that we, St. Augustine parishioners, had defiled the altar. Even my radical Catholic friends who never went to church were appalled by the interruption of mass. They didn’t buy my explanation that the interruption was unwarranted – archdiocesan political high theater calculated to justify the seizing of the blessed bread.

They weren’t impressed by our lawyer’s research about protests in Catholic churches where the purity of the altar was never questioned. One such protest in New York involved gay sex on the altar which was videotaped and broadcast live. The protesters were arrested; but nobody declared a desecration. All our protesters did was silently march and carry cardboard signs with relevant Bible verses.

After archdiocesan agents kidnapped the sacrament I slipped inside the beautiful church to pray one last time. St. Augustine was founded in 1841 so that enslaved people, people who owned slaves, and free people of color could all worship together. I wanted to say goodbye to my favorite stained glass saint, St. Odile, whose luscious gaze meets you head on, and to rescue my booklets called Showdown in Desire. The booklet tells the story of the Black Panthers in New Orleans and prominently features our priest-in-exile Father Jerome LeDoux who tried to broker a peace between the Panthers and the New Orleans police in 1970.

On the sidewalk outside of St. Augustine church where the protesters converged, artists, filmmakers and photographers captured the moment, brass bands performed, good food was served, strategists clicked away on their computers, revolutionaries who had seized the rectory weeks ago climbed in and out of a window, church elders passed the time of day, prayer vigils were held. And the Panther booklet sold like hot cakes.

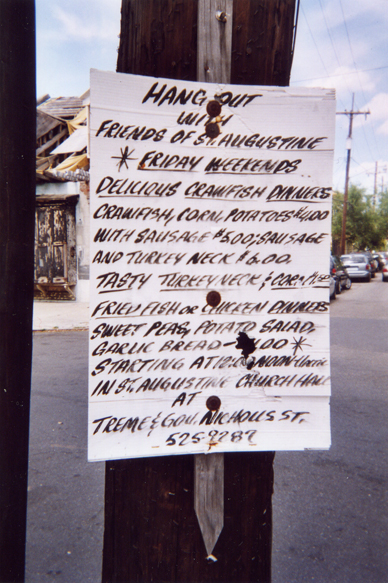

Hanging out!

© Maria Worton

|

One of its chapters recounts the police/Catholic collaboration in 1970 when an officer put on the garb of a priest in order to gain access to the Panther headquarters in the Desire Housing Project early Thanksgiving morning. The police in disguise shot Panther Betty Powell in the shoulder as she tried to shut the door on them. And then they arrested the revolutionary heroes whom the Desire residents had successfully protected during a long, tense standoff a week earlier.

On that Sunday at St. Augustine the collaboration between priests and police wasn’t quite so devious but it seemed like a sacrilege to us, nevertheless. The new priest assigned to take over our parish, Father Michael Jacques, had come with body guards, plain clothes cops. And the cops looked just like ordinary parishioners except that they toted guns beneath their jackets.

The mass did not proceed as expected. Signs popped up behind the interloping priest questioning his veracity, his authority, and his standing with God. Suddenly, seemingly out of nowhere, a procession appeared led by the daughter of the parish council president. As it proceeded down the side aisle with colorful signs the congregation erupted into song and applause. “We shall not be moved.”

The invading priests and guards left, claiming they feared for their safety. They left with such haste that they knocked a sign out of a protester’s hand and Father Jacques’ car hit one of his own parishioners and knocked her to the street. Fortunately, no one was hurt.

The remaining congregation of several hundred souls danced in the aisles, hugged each other, and wept. Then we joined hands and conducted a prayer service.

We expected our church to be shuttered indefinitely. Or perhaps they’d come and tear it down and build condos on the valuable land so close to the French Quarter. Surely the revolutionaries who had barricaded themselves in the rectory these long three weeks would be forcibly removed. Never mind that the beautiful young people whom the press portrayed as heathen, outside agitators were signing up to learn to be Catholics.

True, they had never quite pictured themselves cloistered in church. Many had not even planned to set foot in a New Orleans church until they experienced the spirit at St. Augustine, its Jazz mass, Father LeDoux’s interactive sermons, the incorporation of Kwanzaa, old-time spirituals, and the rhythms and colors of the Mardi Gras Indians. The young people had come to gut houses in St. Bernard and the Lower Ninth Ward. I invited Suncere, who I had recently hired as an AmeriCorps mediator, to a church organizing meeting after the archdiocese had declared our parish dead. Suncere explained to our all-male (except me) organizing cadre how he had expertise in seizing and securing buildings to made a political statement, that he was ready to marshal his forces at a moment’s notice, and to stay for as long as it takes. Ironically, he was fresh out of a post-disaster facilitator training conducted by Ted Quant. I was hoping he had learned those lessons well and that Ted, an experienced mediator, would step actively into his mentoring role.

The organizing committee was impressed with Suncere’s offer. I was wide-eyed and somewhat amused. I couldn’t imagine that we’d get very far with the congregation as a whole, many of whom had never questioned Catholic authority and never openly questioned white authority that I had observed.

Boy, was I wrong! The congregation backed the protesters every step of the way. They said, “Don’t tell us what you are going to do. Just do it. We trust you to represent our interests. And thank you.” Now that’s what an organizing committee likes to hear.

Many of the elders visibly came alive. One soft-spoken senior stood up at a meeting and said, “Just because my skin is light and I have red hair, most people think I never stood up to the Man. But you should have seen me back in the day.” You go, woman. Big Chief Tootie Montana, the “Chief of Chiefs,” an honorable member of our congregation, left this plane before the storm taking a stand for the Mardi Gras Indians. His widow, Ms. Joyce, sat with her friends on the sidewalk for weeks, just daring the authorities to enter our sacred space. We called them “the golden girls.” Tootie, meanwhile, provided extremely practical help from the spirit realm.

Malik Rahim is a key figure in the Panther booklet along with Father LeDoux. In 1970 Malik was in charge of security for the Panthers. He was arrested in the Piety Street shootout and spent eleven long months in jail before Lolis Elie and a team of brave lawyers got all the Panthers acquitted. After Katrina, Malik started Common Ground, a grassroots relief organization, which reminds me of a giant (worldwide) Panther survival program. Suncere came from Washington D.C. to assist him. Malik passed on some of his organizing and leadership skills to Suncere, reminding me that history in New Orleans never has been so much linear as circular.

In 1970 Ted Quant was new in town. One of his first decisions was to stand with the unarmed, mostly young Desire residents who formed a human barricade between the 250 armed white police in riot gear and the Panthers holed up in a Desire apartment. These brave young people precipitated the retreat of the full force of the New Orleans police with their guns, tanks, and helicopters. We have precedent in New Orleans for young people leading the charge against an apparently impregnable authority for a righteous cause.

Ten days after the disrupted mass at St. Augustine, Ted got a call from Father William Maestri, spokesperson for the archdiocese, asking him to negotiate a resolution to the dismal stalemate. It was the last thing I expected deep into this post-Katrina Lent. But that was because I was unaware that our strategists had been contacting mediators, hypothesizing about the interests of the archdiocese, and constructing sensible negotiating offers from day one.

Ted is adept at conflict transformation. He’s head of Loyola University’s Twomey Center for Peace through Justice. But he pointed out that he isn’t neutral. He sides with St. Augustine parishioners. Maestri told him, “That’s OK. We know you can be fair.”

Speculation abounded as to why the Archbishop might change his mind, something that no one in New Orleans could recall happening here ever before. Some said it was pressure from on high resulting from all the bad publicity about hitting people when they were down, taking away their church home after their family homes had been ruined by Katrina. Me, I’ll go with the oft-used Catholic “explanation” which is that some things are just a mystery.

Two days later a settlement emerged. Both sides were pleased, but both had made significant compromises. The parish will remain open and independent. It will get an administrator from Father LeDoux’s order to help us meet benchmarks over the next 18 months. Our beloved pastor-in-exile will be with us again in church on designated Sundays. He’ll travel abroad to promote his historical novel about St. Augustine Church. Even though he is 76 years old, he is no where near ready to retire.

Deep, deep into Lent we could see Easter coming. Father Maestri and Archbishop Alfred Hughes held a service of reconciliation at St. Augustine to bring the sacrament back. It began in the dark. Amid incense and holy water and a sermon about the prodigal son the lights came on. The Archbishop contemplated his own missteps and those of his advisors and encouraged us to do the same. We all shared in the resurrection of mutual forgiveness. A parish which had been pronounced dead came back to life.

The next day, Palm Sunday, Father LeDoux, Archbishop Hughes, and Father Jacques celebrated mass together. They had to remind us that it wasn’t Easter quite yet. Suncere and the Archbishop hugged each other. Malik, who has become a Muslim since his Panther days, worshipped with us on Palm Sunday, honoring his Christian roots.

On Maundy Thursday Father Maestri warned in his homily about the danger of ambitious priests. And then he washed our feet. On Good Friday pilgrims from all over town made our church the third stop as they walked the Stations of the Cross. At the fish fry that evening, stories of the successful mediation were spilling forth like points of light on a star that signifies a miracle.

It was a good Lent. It was a hard Lent. Each of us had participated personally and communally in a first-hand experience of death and resurrection.

END