Messages from the emotional-political landscapes of indigenous ( adivasi ) and ‘untouchable' ( dalit ) women in South-Indian Kerala

Messages from the emotional-political landscapes of indigenous ( adivasi ) and ‘untouchable' ( dalit ) women in South-Indian Kerala

“Where do Kerala women stand?”,

The January 27 th (2001) issue of the well-known Malayalam weekly Mathrubhoomi (Motherland) documented the answers to that question given by those few women whose voices have resisted the silencing powers of Kerala's notoriously hypocritical public and politics.

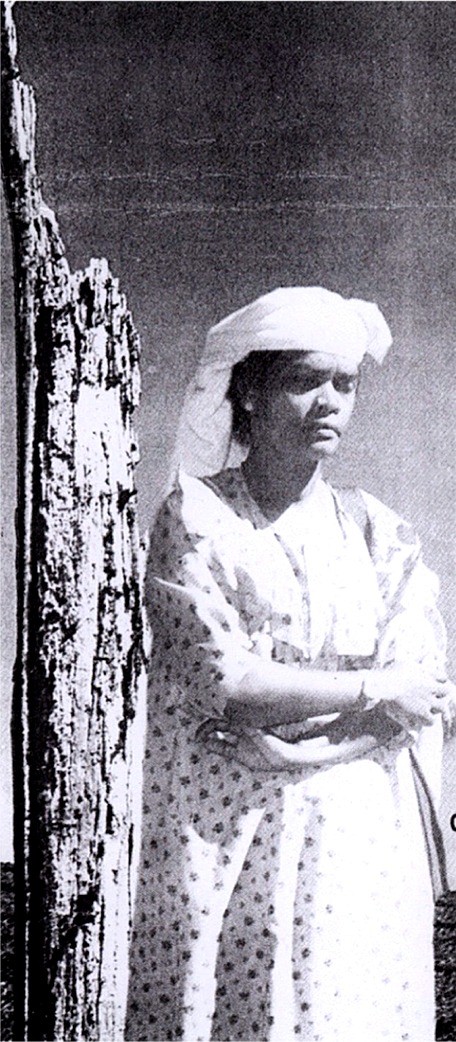

It is particularly the stand taken by C.K. Janu, an energetic woman of Kerala's ‘first humans' (the literal meaning of adivasi ), who is one of the main forces behind the recent uprising of adivasis struggling for their own lands and self-rule, which are worthy of note to international feminism.

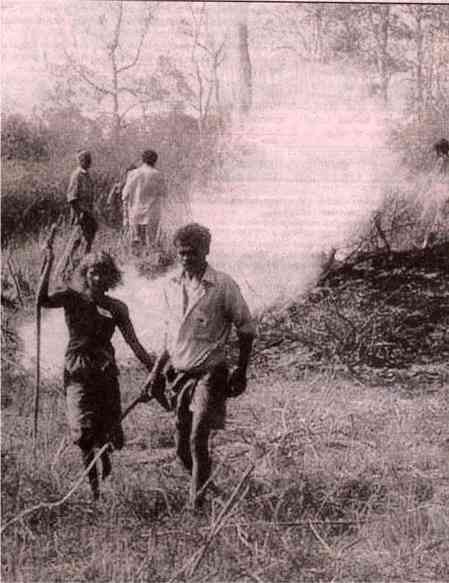

Each of the women interviewed by Mathrubhoomi fought her own fight against the Kerala mainstream society's complicity with the international trend towards the total commodification. There is, for instance, K. Ajitha, who once had been a Naxalite struggling – amongst other causes – for adivasis . But today there is C.K. Janu, an adivasi woman. For the first time in Kerala's long history of violence against adivasis and their original habitat, the forest, which was their ‘mother' who nourished adivasi cultural identity and livelihood, an adivasi woman rises her voice, moves ahead of an adivasi resistance which cannot be brushed aside easily.

It is the absolutely novel type of the ‘feminine spell', the profoundly humane vision of life which this woman of the Adiya tribe exercises on the Kerala society – a society which is generally referred to as a paradise to its women for the mere fact of its literacy levels and the female side of the gender ratio being higher than in most of the other Indian states.

In sharp contrast to this myth woman activist K. Ajitha begins her answer to the above cited question on the status of Kerala women with the following statement :

“Today's condition of Kerala's women reveals hard facts about a state which is internationally known for being a development model. Domestic violence and its ill effects on women increased drastically. A comparative study conducted by a group of doctors in Thiruvananthapuram points out that in Kerala violent incidences in the family are more frequent than in backward states like Uttar Pradesh and Bihar. The dowry deaths and suicides are rampant. Harassment of wives rises daily while the number of women who approach the Family Court for divorce and for claiming subsistence allowance are less. The relationship between husband and wife became extremely tensed, and the children who have to live under these conditions became a social problem. It is the race for money and existence which lead to this familial environment and thus ended up in that unhealthy social situation.”

An adivasi woman's vision

In the following C.K. Janu's views are documented extensively because they differ essentially from analyses usually hold by (urban) women on women's issues. C.K. Janu has an ‘organic', vital relationship with the ‘real' and everyday life experiences of Kerala's marginalised, with their dreams and with their fears. Janu's perspective speaks for itself; however, in my concluding paragraph I will further reflect on that ‘magical emotional' facet in her thinking, her relationship to people, in her struggle, which I consider to constitute one of the most rich sources to any feminist or humanist today who is heading towards a life centred around the human being-in-nature; to anyone who wouldn't allow the violent forces based on overall capitalist production to systematically destroy or transform life sources into resources for profit making, exploitation and estrangement.

Under the headline “A woman should realize her power” C.K. Janu wrote:

“ [...] Violence against women, rape, sexual harassment which often ends in murder, suicide etc. increased. The tendency to consider a woman a commodity also increased.

I don't think that [Indian] women are adequately represented in the political or social sectors. Even in the family she is not granted her proper position.

It is true that some women have entered the political sphere. A few have come into power also. But the entry of one or two into the arena of political power cannot be considered as social change. It is only an individual gain. However, if one studies the status of women in general, one finds that women are denied even basic rights in their houses.

Before independence the tribal world was much different: ‘a group of savages in slavery and with empty bellies'! But despite of their poverty and unpolishedness, unwed mothers, sexual harassment, or suicide were unheard of then. Culture was a composite of their life, and one tried to preserve the tribal heritage. A tribal women didn't suffer such that her whole being would have been at stake.

Today the situation is totally different. Civilisation and education became accessible to the tribals, and from then onwards sexual harassment, illegitimate pregnancies and suicides are spreading. A murder after sexual harassment is usually written off as suicide, or unnatural death.

In the tribal society, women's freedom was greater. If today the influence of women in society and family increased, it is mainly because of alcoholism among men. As the number of alcoholics increased in most of the families the woman has to take up the responsibility of being the “head of the household”. Now women do not only deal with financial matters but also take decisions. They do also respond and speak out against injustice . Only a handful of women consume alcohol.

Adivasi women are treated equally on all levels. Generally in families, major positions are given to girls. They usually get special consideration, even equal property rights. [...]

Tribals do not sell their women as a commodity as it is done in the dowry system. A man will marry a woman only after some money was given to her. As an exception, Kani tribal men near Thiruvananthapuram receive dowry. Thus, because of the excessive encroachment of civilisation, it remains unpredictable whether the dowry system will also spread among adivasis.

Attempts to bring adivasis into the mainstream of society will mostly end up negatively. The greatest problem is that a child who feels ashamed to be an adivasi might consider civilization as good. When girls (and boys too) are educated, they tend to imitate the civilized. But the civilised will not consider them as equals. By then, our children are between the devil and the deep sea.

Children in government financed tribal schools are isolated from their parents, tribal customs and adivasi culture during the formative period of their lives. Books will lead him or her. The life relationship is lacking. They will be reluctant to say they are adivasi, and might disown their own parents in public.

The moment tribal children are educated, often they tend towards humiliating or desecrating indigenous customs and traditions. Beating the thudi (a percussion instrument), singing, dancing, and so on are considered as primitive.

But, recently an awakening happened. Youngsters have come forward with that asserted awareness: “we are one”. Even if discouraged, they will beat the thudi and jointly dance during reception meetings and others. They started to understand that they don't have any existence by discarding their own tribe's heritage.

Whenever any woman is facing a problem, each one of us should willingly empathise with her: “I am that woman!” That attitude and feeling ‘It happened to her, not to me' doesn't help us to further mature.

When women hurray “Jai” to the colours of the flag, to the colour-caste-creed difference their status will remain the same. But nothing is impossible to women who jointly stand together without considering the colour-caste-creed distinction, or the political party's colour of the flag.

We often committed mistakes while defining the problems of women: there is nothing like women-only problems. Mostly they are the problems of society in general. For example, prostitution. There is no prostitution without the involvement of men; and the beneficiary is men, too. Therefore, one has to see it as a problem of society at large.

We never form women's organisations among tribals. Tribal organisations deal with the problems of their community as a whole.

If women organise, it is unlikely that they would think or act adversely against the society. I don't think a woman who comes into power will harm society. Because what she learnt in the context of family she will not forget while being in power. But she shouldn't be a puppet in the hands of men. In that case she would support injustice.”

The power of ‘female empathy' on the basis of humanness instead of ‘communalism'

C.K. Janu stresses the potential of empathy in women and its healing capacity to the whole community. This is what interests me here, so I won't go into a detailed discussion of her general trust in ‘women in power'.

As a woman, a social and media activist and as a university scholar I was cooperating with new people's movements in India since more than a decade; for three years I was accepted as a partner by dalit and adivasi women's groups in Kerala in their own efforts to inscribe their ‘life stories' by means of telling, writing and – with my support – by (video) film making into our world's memory. On the basis of having been a sympathising witness to their creative filmic representations of their lives which they allowed me to ‘enter' with my video camera under their ‘direction', I became humble vis-à-vis their compassionate ways of thinking, acting, communicating and representing ‘themselves-to-others'. What I encountered always and what later I called their ‘ethics of sneham / love' was always accompanied by their strong sense of niti / justice. Their ‘identity' as a dalit or adivasi woman isn't spelled out in a possessive or excluding manner. So, their ways of ‘answering' that same question:

“Where do I stand as a woman in Kerala” very much complement C.K. Janu's “I am that woman!” and this feeling of Self-Other (‘society'), of her relationship to the ‘land' is indeed women's bare feet walking from village to village, her working on that bhoomi (land); it surely contrasts the mathrubhoomi (‘motherland') captured and utilised by politics.

However, the recently emerging dalit - adivasi alliances in people's struggles in Kerala reveberate on the society's level what individual women like C.K. Janu, or other adivasi and dalit women practise in their daily lives as empathic emotions to make that first people's culture of a balanced life grow. But there is not much space, there isn't also much time left. A young dalit woman P. who is an attentive observer of the ongoing state and mafia violence in Kerala expressed her conclusions and her fears to me in December 2003 as follows:

“This is actually homicide, the mainstream society wishes to destroy, to uproot the indigenous society because there is no use of them. The whole world goes like this ... after ten to fifteen years there will be no indigenous people. [... they would have to] come together [and ...] distance themselves from the mainstream society [...] my solidarity is always with [the adivasis ...] I see them as human beings as I see myself, and they have their right to live on this earth, we are the real heirs of this earth [...] B.Schulze: Are you scared? P.: Yes.”

For further reading, for information and contact please visit the following websites:

www.re-wo-man.net

www.femCineCult-kerala.uni-trier.de

1) I am grateful to Joseph Korula for his translation from the original Malayalam into English.

2) An in-depth research by one of Kerala's most recognised women's organisation SAKHI provides the basis of facts& figures to K. Ajitha's argument: Support Services to Counter Violence against Women in Kerala , A Resource Directory published by Sakhi Resource Center for Women, Thiruvananthapuram, Kerala, India, in collaboration with UNIFEM South Asia Regional Office, New Delhi, February 2002.