PI: a film review

John D. Devine

[The Sundance Film Festival award for best director went

to Darren Aronofsky].

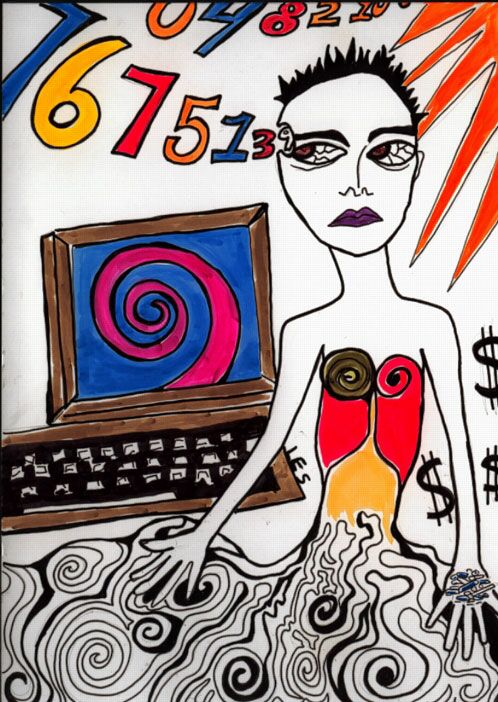

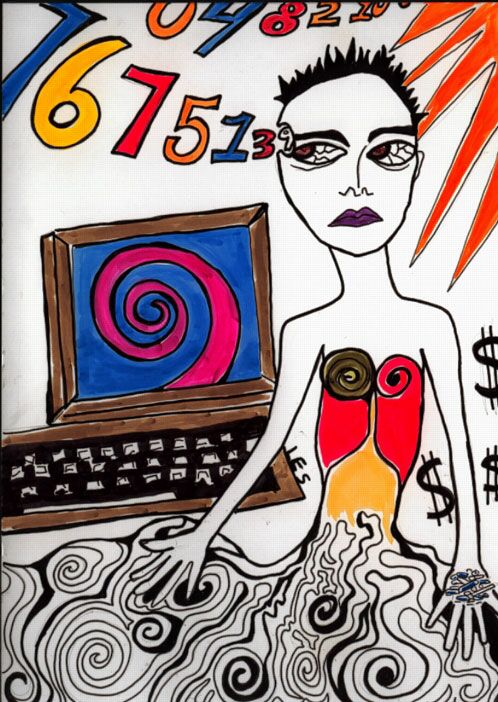

I have just viewed a superb film, Pi, directed by Darren Aronofsky. At the

opening of the film Max, the protagonist, lies bleeding from his nose on the

floor, having suffered an attack, a spell which wracks his brains but always

begins with his right hand. He tells the audience he suffered his first attack

when he was six, while looking directly into the sun. For a moment, he says,

he saw everything. And then nothing.

Max, now a man, studies the stock market and models it on a

computer after a celebrated Greek mathematician. Each day he enters the returns,

which are used to compute the next day's returns. These numbers are accompanied

by a 216-digit number, which inevitably crashes the whole system. His teacher,

Sol, abandoned the same project after suffering a stroke; a stroke he says was

caused by his study of pi.

In a diner Max meets 'a religious Jew,' Lenny, who is studying

the numbers of the Torah. Hebrew, he tells Max, is all numbers. Every letter

corresponds to a number. The word for Tree of Knowledge divided into the word

for Garden of Eden results in a Fibonacci sequence. The number-word for God

has 216 letters. Max suffers another attack, flees and puts a handful of pills

into his mouth.

One,

of course, may begin to wonder what the stock market has to do with God, or

'pi' to do with life. Life, it could be said, has a circular form. One speaks

of circles of affair, or, in a dimension of depth, spheres of influence. One

jumps from circle to circle and in doing so moves from one sphere of influence

to another. One goes from one's family's affairs to community affairs, or from

world all the way to cosmic affairs. Circles of affairs, as an economic model,

date back to Plato, who compares the emotions to a coin: emotions have a value

that can be spent or invested. It is frequently said that one has interest in

a particular thing, or that one has lost interest; these are quantitative expressions.

One is said to make an emotional investment, a bid for someone's love. In a

very real sense the full range of human expression does not differ much from

its meaning (fluctuation) in the stock market; something appreciated takes on

a greater value. Or an event is said to be taxing. The circles ensure that everything

will return to its opposite: joy will become grief, life will become death.

In the center of the circle is God. Pi is the ratio of the radius, the straight

line to God, to the circumference of the circle encompassing everything drawn

into it.

One,

of course, may begin to wonder what the stock market has to do with God, or

'pi' to do with life. Life, it could be said, has a circular form. One speaks

of circles of affair, or, in a dimension of depth, spheres of influence. One

jumps from circle to circle and in doing so moves from one sphere of influence

to another. One goes from one's family's affairs to community affairs, or from

world all the way to cosmic affairs. Circles of affairs, as an economic model,

date back to Plato, who compares the emotions to a coin: emotions have a value

that can be spent or invested. It is frequently said that one has interest in

a particular thing, or that one has lost interest; these are quantitative expressions.

One is said to make an emotional investment, a bid for someone's love. In a

very real sense the full range of human expression does not differ much from

its meaning (fluctuation) in the stock market; something appreciated takes on

a greater value. Or an event is said to be taxing. The circles ensure that everything

will return to its opposite: joy will become grief, life will become death.

In the center of the circle is God. Pi is the ratio of the radius, the straight

line to God, to the circumference of the circle encompassing everything drawn

into it.

Recently it has been suggested that the stock market is the

most perfect model for 'libidinal' economies because it is a self-consistent

aggregate which touches every circle of affairs. The fact that it is self-consistent

insures that it will be cosmic because the cosmos, by its nature, endows everything

with consistency. The circles do not represent totality, although they encompass

virtually everything. One can move in a straight line from circle to circle,

just as the circles move in a spiral that emanates out from the second circle

leaving the inner circle intact. This spiraling movement is a Fibonacci sequence.

A Fibonacci sequence is any series of numbers where each number is the sum of

the two preceding numbers: 0, 1, 1, 2, 3, 5, 8, 13 . . .

As Max learns of the mystical connection to his research, he

becomes all the more convinced that his model is correct, despite the discouragement

of his teacher who sports a tattoo of the sun on his right hand. "This

is madness," he says. Sol gestures with the tattooed hand to his goldfish

Icharus named in honor of Max. Do not go so close to the sun, he tells him,

or you will get burned.

Max persists. "The stock market: millions of hands, billions

of minds." One thousand times as many minds as hands. All producing numbers.

Somewhere, behind the numbers, Max is convinced there is a pattern. His computer

is infested with ants that secrete a sticky substance on the main processor.

Under a microscope he discovers that the secretion appears as a spiral, a capital

letter G.

Inevitably, Max begins to succumb to paranoia. His corporate

investors have him followed and photographed. Spirals appear in every direction,

in swirls of smoke, in milk, in his coffee, seashells. As the spirals multiply

his paranoia multiplies, and his attacks become more severe. The religious Jews

follow him. Then there is the matter of his paranoia in the stairwell with the

girl next door who is courting him. Max takes pains to avoid her.

Finally, after having discarded it, Max rediscovers God's number

using a computer chip given to him by his corporate investors. He betrays them

by refusing to give them the number. They threaten him with a gun and he is

rescued at the last moment by Lenny who takes him to the religious Jews' inner

sanctum, to the inner circle of the temple. There everything religious and mystical

concerning the number is explained to him. It is as if the priests knew everything

but the number, which Max refuses to divulge. "It's in my head. It was

given to me."

In the final scenes Max's teacher dies of a stroke when he

tries to decipher the number. The number not only crashes computers but also,

Sol tells Max, makes the computer conscious. Max decides the 216-digit number

is ultimately responsible for his own ill health and drills a hole in his own

skull. This procedure, called 'trepanation', was used by primitives to divest

a person's head of evil spirits. God, it turns out, was nothing more than an

evil spirit who must be driven out.

CREDITS

Written by Darren Aronofsky

Sean Gullette as Max

Mark Margolis as Sol

Ben Shenkman as Lenny

Written and directed by Darren Aronofsky, Sean Gullette and Eric Waston

THE END

Voice Your Opinion

- Back to

the Table of Contents - HOME

One,

of course, may begin to wonder what the stock market has to do with God, or

'pi' to do with life. Life, it could be said, has a circular form. One speaks

of circles of affair, or, in a dimension of depth, spheres of influence. One

jumps from circle to circle and in doing so moves from one sphere of influence

to another. One goes from one's family's affairs to community affairs, or from

world all the way to cosmic affairs. Circles of affairs, as an economic model,

date back to Plato, who compares the emotions to a coin: emotions have a value

that can be spent or invested. It is frequently said that one has interest in

a particular thing, or that one has lost interest; these are quantitative expressions.

One is said to make an emotional investment, a bid for someone's love. In a

very real sense the full range of human expression does not differ much from

its meaning (fluctuation) in the stock market; something appreciated takes on

a greater value. Or an event is said to be taxing. The circles ensure that everything

will return to its opposite: joy will become grief, life will become death.

In the center of the circle is God. Pi is the ratio of the radius, the straight

line to God, to the circumference of the circle encompassing everything drawn

into it.

One,

of course, may begin to wonder what the stock market has to do with God, or

'pi' to do with life. Life, it could be said, has a circular form. One speaks

of circles of affair, or, in a dimension of depth, spheres of influence. One

jumps from circle to circle and in doing so moves from one sphere of influence

to another. One goes from one's family's affairs to community affairs, or from

world all the way to cosmic affairs. Circles of affairs, as an economic model,

date back to Plato, who compares the emotions to a coin: emotions have a value

that can be spent or invested. It is frequently said that one has interest in

a particular thing, or that one has lost interest; these are quantitative expressions.

One is said to make an emotional investment, a bid for someone's love. In a

very real sense the full range of human expression does not differ much from

its meaning (fluctuation) in the stock market; something appreciated takes on

a greater value. Or an event is said to be taxing. The circles ensure that everything

will return to its opposite: joy will become grief, life will become death.

In the center of the circle is God. Pi is the ratio of the radius, the straight

line to God, to the circumference of the circle encompassing everything drawn

into it.