[It has taken the greater part of 20 years for recognition

to come to Montreal-born artist Liane Abrieu. Taking time from a busy schedule

(she works between 40-50 hours per week on canvases that take a minimum

of one month to complete), she granted Montreal Serai an interview in her

quaint, rustic home in the village of St-Philippe, 30 minutes south of Montreal.

Liane Abrieu began exhibiting in 1980. Her works have appeared at the Montreal

Museum of Fine Arts, the Historic Museum, the Shayne Gallery, and most recently

the prestigious Perry Gallery in New York.] ed.

SERAI:

When I look at your work, I see everywhere meticulous detail and labor-intensive

precision. You've mentioned that it takes approximately 250 hours to bring

one of your works to completion. A minimalist artist, on the other hand, requires

perhaps no more than an hour to conceive and execute a few stripes, or a monochrome.

On top of that, he will have received considerable grant money, reviews in

all the journals and newspapers - while you, (the real artist), continue to

struggle for recognition. Does this infuriate?

SERAI:

When I look at your work, I see everywhere meticulous detail and labor-intensive

precision. You've mentioned that it takes approximately 250 hours to bring

one of your works to completion. A minimalist artist, on the other hand, requires

perhaps no more than an hour to conceive and execute a few stripes, or a monochrome.

On top of that, he will have received considerable grant money, reviews in

all the journals and newspapers - while you, (the real artist), continue to

struggle for recognition. Does this infuriate?

LIANE: I don't begrudge the minimalist artist. When I

first discovered Jackson Pollack, I liked what I saw. He was a pioneer.

If it wasn't him, someone else would have artistically expressed himself

by throwing paint at the canvas. But you can only go so far with this. The

same with the minimalists. Someone had to do it, they've had their day in

the sun, and now I believe it's over. You can only do so many variations

of stripes and bars before it becomes redundant. And the consumer can only

hang so many of these works in his living room before they begin to look

like wallpaper. Yes. The huge sums of money these people have received have

angered me. The reason I moved to St-Philippe many years ago was because

the rent was $90/month. But these granting agencies have shot themselves

in the foot because the artists they have supported have mostly gone nowhere;

they haven't developed, and I believe that most of them will be forgotten.

And the art critics who have staked their reputations on this stuff will

have lost credibility. What goes around comes around. But to be honest,

I can't concern myself with what other artists are doing. I have my own

visions and work to complete and there is never enough time.

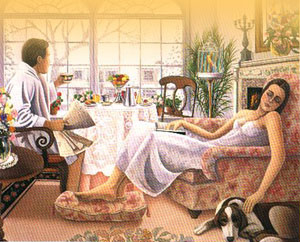

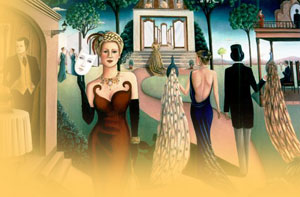

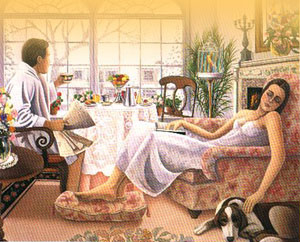

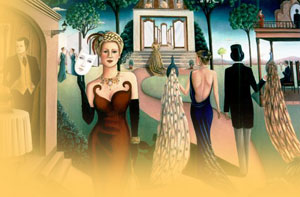

SERAI: Your works feature people who are very refined and

serene, placed in sumptuous settings, surrounded by elegance and plenitude

- even aristocratic trappings. These people are decidedly not at all concerned

about what's happening in war-torn Yugoslavia, or Chechnya and Africa. Are

you eschewing politics altogether, or is there a politic in your work?

LIANE: It's not my place as an artist to document what's

happening in the places you have mentioned. I haven't suffered their suffering.

I can't talk about starvation because I have never been that deprived. And

we are so much more aware of it today because of the revolution in communications.

So if the misery has already been documented, I simply don't see the point

in adding to it. I do know that much closer to home there is a different

kind of suffering which can be very difficult in its own way. What the world

needs is more beauty in it; and this is something I can give. My work isn't

for everybody. Not everybody is ready for beauty.

SERAI:

What do you mean by that?

SERAI:

What do you mean by that?

LIANE: I think certain things have to happen during one's

life for beauty to make a difference. I guess everyone has to suffer the

realization, each in his own fashion, that there isn't enough time in a

life time to do everything we would have liked, that one day we are going

to die and that will be the end of beauty. For these people, I hope I can

make a difference. When someone tells me that they have problems or have

been depressed, but after looking at my work it makes them feel good, that

they have been able to clear their minds - if only for a while -- I feel

that I have accomplished something, that I have contributed something to

the world.

SERAI: There is a wonderful social life going on in your

paintings; groups of people, mostly elegant women, enjoying each other and

life. How does this connect to your personal life?

LIANE: I'm actually a very solitary person. I need my

solitude to work. I would like to be with these people in my paintings and

I suppose I envy them in a certain way, but I know it wouldn't be me. At

the same time it's not easy being alone for most of the day; but I really

don't have a choice. People are surprised to learn that I'm not part of

an artistic community. I suppose there are times when I would like to talk

with other artists to discuss mutual problems, encourage each other. But

outside of my family, I just don't have time or the inclination to be with

other people.

SERAI: Returning to your pre-occupation with beauty. How

do you respond to the "truth is beauty" argument?

LIANE: What is truth? It varies from one person to the

next. When I was younger I took certain things for granted; I passed over

beautiful things because I didn't see them. What was beautiful for someone

else didn't exist for me. But it was always there. I don't think I could

ever paint a war scene, or something ugly. Even if it does represent a certain

truth, it's only one kind of truth. Another truth is that we sometimes need

to escape from ourselves, from the pressures and stresses of life. For some,

it might be through drugs and alcohol, movies or soap operas; for others,

perhaps through art. I would like to transport the viewer to an ideal world,

where people are civil and considerate of each other, to an architectural

order that is pleasing to the eye and harmonious with nature, where poverty

has been eliminated. Call it a dream world if you like, but if we can't

dream of better places they will never become real, actual. The abundance

that we enjoy now was nothing but a dream in the Middle Ages. Maybe one

day what you see in my paintings will be real. I would love to be as happy

as the people in my paintings.

SERAI:

So you're an idealist.

SERAI:

So you're an idealist.

LIANE: I love beautiful things much more than labels.

I can only say that I am thankful that I have been given a certain gift,

which I feel obliged to use and share with others.

SERAI: Sharing what exactly?

LIANE: A few years ago someone brought to my attention

that there is a moral presence in my paintings. So now, when I'm in the

presence of something beautiful, I feel that I have come in contact with

something moral that I would like to share with others. It's hard to explain.

I'm attracted to people who conduct themselves in an orderly fashion; I'm

attracted to orderly scenes in life.

SERAI: Many Quebec artists are ardent nationalists. Are

you?

LIANE: I'm concerned that the French language, my mother

tongue, may, in fact, one day disappear. But that's due to globalization

more than national politics. There are lots of things besides French that

are being threatened by globalization. In fact, you could say that 'all'

the cultures of the world are being threatened by the culture of technology.

When I conceive of a work, I'm not thinking politics if that's what you're

asking.

SERAI: And if someone were to spin a nationalist interpretation

on your work?

LIANE: (Laughing) I can't imagine that. Just like I can't

imagine our Prime Ministers and Premiers going to museums - maybe in Europe,

but not here.

SERAI: It's difficult to assign a genre to your work.

LIANE: That's very true. It's not realism but it's not

exactly surrealism either, nor is it symbolic or allegorical - maybe all

of the above. Some people see the influence of other artists in my works,

but this is unintentional. They have asked me if I have been influenced

by Magritte or Delvaux - and I have had to tell them that I am very unfamiliar

with the history of painting and hadn't heard of the these people. Now that

I know them I understand where they are coming from. I paint what I paint

because I'm moved by what I imagine. There is something that I must express.

If I don't feel it I'm not going to paint it. I don't study other painters.

I don't even use models.

SERAI: Again returning to the notion of beauty. Is that

all that is required of painting - that it be beautiful?

LIANE: We are living in a time where extraordinary importance

is placed on beauty. We want our boyfriends and girlfriends to be beautiful,

even though we recognize that being beautiful, or good-looking doesn't mean

that you are good. In other words much of what is considered beautiful is

superficial. But that is what we are conditioned to look for, and we believe

we are happy when we find it. Unfortunately, the same holds true in the

visual arts where the consumer is looking for the equivalent of a beautiful

blond he can hang on the wall. And while a particular minimalist painting

might be beautiful, pleasing to the eye, after while you realize there's

nothing there. But this is what the consumer wants - and he will pay top

dollar for it. I think of my work as an alternative to what's out there

- and that it's meaningful to other people because what is there will be

there for a lifetime.

SERAI: Does it hurt to part with a painting?

LIANE: Some of them - yes. But it's also nice to know

that my paintings are living independent lives elsewhere, are bringing people

pleasure in places as far away as England.

SERAI: Have you made any concessions to the public?

LIANE: I think I would be more surrealist, perhaps a bit

more morbid if I didn't have to concern myself with making a living. But

I don't think I'm compromising my visions and feelings. At the same time

I'm aware of what people are willing to hang on their living room walls.

I could paint a beautiful spider about to devour its prey, but who wants

it.

SERAI: Does having to make these concessions bother you?

LIANE: Not really. Artists from time immemorial have been

commissioned by city states, or emperors and municipalities to do art. As

you can see, I'm more or less doing exactly what I want.

SERAI: And for that, the art world is all the richer. Thank

you, Liane Abrieu.

SERAI:

When I look at your work, I see everywhere meticulous detail and labor-intensive

precision. You've mentioned that it takes approximately 250 hours to bring

one of your works to completion. A minimalist artist, on the other hand, requires

perhaps no more than an hour to conceive and execute a few stripes, or a monochrome.

On top of that, he will have received considerable grant money, reviews in

all the journals and newspapers - while you, (the real artist), continue to

struggle for recognition. Does this infuriate?

SERAI:

When I look at your work, I see everywhere meticulous detail and labor-intensive

precision. You've mentioned that it takes approximately 250 hours to bring

one of your works to completion. A minimalist artist, on the other hand, requires

perhaps no more than an hour to conceive and execute a few stripes, or a monochrome.

On top of that, he will have received considerable grant money, reviews in

all the journals and newspapers - while you, (the real artist), continue to

struggle for recognition. Does this infuriate? SERAI:

What do you mean by that?

SERAI:

What do you mean by that? SERAI:

So you're an idealist.

SERAI:

So you're an idealist.