I — Mimesis

Beyond all the special effects in the world of 2014, behind the digitalized technologies, the espionage, the surveillance, the intrusive computer viruses, the attempts to create self-conscious machines and even to cook up new universes – behind all this present activity lies the ancient human drive to reproduce reality. In his Poetics Aristotle long ago defined human art as an act of mimesis or imitation because “Imitation is natural to man from childhood, one of his advantages over the lower animals being this, that he is the most imitative creature in the world, and learns at first by imitation.” Aristotle added as well that although certain objects, such as dead bodies, may be painful to see, “we delight to view the most realistic representations of them in art” because through such unpleasant visualization, we learn more about reality.

The Australian anthropologist and anti-colonial theorist, Michael Taussig, has updated Aristotle with a vivid explanation of how Taussig thinks imitation works in our own age. Mimesis, he, says involves

…the nature that culture uses to create second nature, the faculty to copy, imitate, make models, explore difference, yield into and become Other. The wonder of mimesis lies in the copy drawing on the character and power of the original, to the point whereby the representation may even assume that character and that power. (Mimesis and Alterity)

It is a commonplace observation, but a true one, that in the 21st Century– what Taussig calls our “era of mighty mimetic machinery” –we humans have greatly increased the power of creating a “second nature.” Only a short time ago, we would point to nuclear weapons ,“the light of a thousand suns,” to indicate how ramified our scientific constructions have become and our capacity to manufacture large-scale death.

But new techniques of representation now allow us to create or simulate life, rather than death, in ways that we also never imagined. The stakes of the age-old game have become much higher. Thanatos and Eros, Death and Life, sit at the gaming board while the spectators – Fate? History? God? Time? – watch and count the moves.

The theme of this issue of Montreal Serai is “virtual reality,” and strictly speaking that term refers to the computer simulation of a three-dimensional environment with which human beings can interact in a physical way.

For most people, however, “virtual reality” has come to stand for the whole gamut of reproductions that surround us in the digital, electronic world, and at the center of this hyper-environment are the techniques of replication. They, in turn, depend upon the basic modeling processes and acts of mimesis that have shaped modern scientific discovery.

Furthermore, imaging technology has become so developed that it has become ever more possible to model not just real objects but imaginary constructs as well. More and more keenly we are imitating both nature and the second nature of human ideas.

II – Rosalind Franklin

We are surrounded by copies of all sorts, and the many kinds of uncanny replication – such as skillful special effects in a film – provoke an inner unease. Virtual Reality, in this sense of mimetic reproduction, produces a frisson like that evoked by a mannequin bearing a disturbing resemblance to a person we know. We wonder about what is real, and “What is life?”

Indeed, if one were to seek a starting-point for The Age Of Virtual Reality it could be said to have begun on April 25, 1953 when James D. Watson and Francis Crick published a short article in the science magazine Nature describing the double-helix of genetic material. “We wish to suggest a structure for the salt of doxyribose nucleic acid (D.N.A.),” the two researchers began, and then added: “The structure has two helical chains each coiled round the same axis.” The staircase-like form that Watson and Crick outlined rested on a beautifully symmetrical pattern of four molecules with certain pairs (adenine and thymine; guanine and cytosine) always bonding with each other. DNA is what mathematicians call a base-four code, and the two scientists laconically observed: “It has not escaped our notice that the specific pairing we have postulated immediately suggests a possible copying mechanism for the genetic material.”

The discovery of the genetic code had begun.

Watson and Crick won the Nobel prize for their work, but many other people contributed to the breakthrough, and one of the crucial figures – Rosalind Franklin – was treated very shabbily.

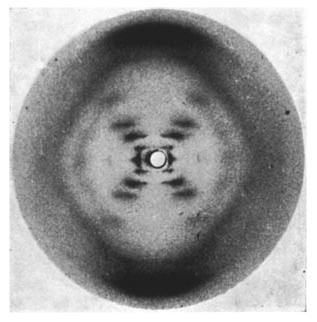

She is all-important in the story of life. An immensely clever, inventive physical chemist and crystallographer, Franklin was in her early thirties at the time. She it was who took the crucial two-dimensional X-ray diffraction photographs that revealed the 3-dimensional structure of the molecule. Her plates were shown, without her knowledge, to James Watson and Francis Crick, allowing the two men to confirm that their model conformed to the structure of the DNA. The Marxist scientist, J.D. Bernal, himself an expert in the imagining, and imaging, of molecules, said of his young female colleague: “As a scientist, Miss Franklin was distinguished by extreme clarity and perfection in everything she undertook. Her photographs are among the most beautiful X-ray photographs of any substance ever taken” (quoted in the Prologue to Rosalind Franklin: The Dark Lady of DNA, Brenda Maddox, Perennial, Harper Collins, 2002).

What was Franklin doing? Making and interpreting extremely refined 2-dimensional representations of real structures existing in three dimensions. The lab techniques she used stem from approaches and protocols that are ultimately linked – via the sketchbook and the camera — to the development of linear perspective by the Italian painters of the Renaissance. In her scientific work, the art of mental reproduction was used (camera, x-ray diffraction plate) to peer into the process of physical reproduction itself. Watson and Crick were, if you will, the sculptors of the DNA model; Rosalind Franklin was its painter. Biographer Brenda Maddox, like many other observers, has pointed to the deep inequality involved in this awkward collaboration: “It had not escaped Watson’s and Crick’s notice either that Rosalind’s work was fundamental to their discovery and that they had not consulted her about its use.”

Virtual Reality… Simulation…Science… Art… Perhaps all of these things at once…Whatever word you use for the discovery of DNA, the real questions concern the work itself. What was the aim of the discovery? Whom has it benefited? Did the workers who made the breakthrough share the credit? If not, why not? Rosalind Franklin was female, Jewish, and a member of a Liberal London family. The urge, even the need, to diminish her role indicates that all human inventiveness demands that we look at who is doing what for whom, and to what end – and that Marxian question is especially important when it comes to Virtual Reality.

As her story has made itself known, Rosalind Franklin has become a symbol of something very basic. Behind all science, and within every new technology, there are always purposes and facts that are occluded, both willfully and unconsciously.

In the modern period, our sense of reality itself has also been greatly extended to include an array of conceptual objects so it becomes much easier to be dazzled and mystified by the “effects” of a technique, and sometimes harder to see the actual ongoing work. Nonetheless, who is doing what to whom is always the vital issue, whether it is a weapon that is affecting people’s lives or an apparently innocuous entertainment film.

III – Jean Baudrillard

The most famous book on Virtual Reality and replication, Simulacres et simulation, was published in 1981 by the French sociologist and philosopher, Jean Baudrillard, and it has been translated by Sheila Faria Glaser as Simulacra and Simulation for The University of Michigan Press (1994). This text was one of the sources for the Wachowski brothers’ 1999 film The Matrix that for many people stands as the most convincing evocation of a world of simulation.

Baudrillard’s text is insightful, provocative, funny – and also terribly wrong.

His argument centers on contemporary capitalism, its techniques of reproduction, and their effects on society.

Before his death in 2007, Baudrillard exercised a great charm for students and certain colleagues. His was a gentle, bespectacled face of a man who seemed to have the outdoor look of his farmer ancestors in the North of France. Behind the quizzical eyes, though, lay a tremendous, fiery anger at the modern world and a capitalism that he felt had destroyed some of his most cherished ideas. To him it has become a system of naked terror. In his remarks “On Nihilism” at the end of Simulacra he talks about “the unbearable limit of hegemonic systems” and proclaims: “I am a terrorist and nihilist in theory as the others are with their weapons. Theoretical violence, not truth, is the only resource left to us.” Modern human beings he thinks – and he includes himself with almost masochistic pleasure – are mere simulacra and mirrors, nothing else, caught in the vast auto-da-fe of “the death throes and apogee of capital,” a system that he sees as full of “its instantaneous cruelty, its incomprehensible ferocity, its fundamental immorality.” We must not, however, “refuse the intense fascination that emanates from this liquefaction of all power, of all axes of value, of all axiology, politics included.” Baudrillard instead believes that people must yield to this “degree zero of meaning” and give up any false posturing of reasoning in the face of our own spiritual annihilation. Simulacra ends with an apocalyptic death grimace: “There is no more hope for meaning. And without a doubt this is a good thing: meaning is mortal.”

Baudrillard’s sociology derives from French contemporaries, but also Adorno, Walter Benjamin, the Frankfurt School, Herbert Marcuse, and Marshall McLuhan. There are as well affinities with deeply conservative thinkers – Nietzsche of course, but also, I would say, even with figures such as Charles Maurras, an early 20th century ideologue of the “organic” French Right .

The central argument in Simulacra, apart from all its antecedents, does touch on something very compelling: a pervasive, alienated feeling of generalized unreality. And Baudrillard deliberately refuses to pull back from the sense of complete vertigo this alienation brings about. Baudrillard claims that we now live in a world of simulacra that have completely replaced real objects. Simulations of reality now relate and connect only with each other.

The logic of simulation, Baudrillard says, has nothing to do “with a logic of facts and an order of reason,” because with simulation the model precedes the fact, and the cycle of communication occurs from model to model with no intervening real events at all. The image – in film or on TV – has “no relation to any reality whatsoever: it is its own pure simulacrum.” The whole connection between a signifier (a word) and the signified (a real object), form and content, illusion and reality, subject and object, cause and effect, the active and the passive, end and means – this whole web of meaning becomes destroyed through a closed, tautological system of mere simulations.

“Explosion,” as Baudrillard describes what “used to be” the violence of history, carried with it, back in the day, the promise of revolutionary change in the old “golden age” of “capital and revolution,” but the contemporary world is now implosive in a dispensation that is completely immanent, with no possible transcendance, and all energy is frozen in the black hole of simulation. “There is no real” and “the social” is “now nothing but a special effect.”

One of the metaphors Baudrillard uses is a nuclear power station – surveillance has been replaced with a system of complete deterrence, manipulation, and universal security, a downward, diminishing vortex that produces a vertigo of the model “which unites with the model of death.”

A second metaphor that he calls upon is DNA, and especially cloning, since the cultural condition that he describes means we are “in the service of a matrix called code.” So, the DNA molecule is “the prosthesis par excellence,” an artifact “from which will be able to emerge…identical beings assigned to the same controls.” For Baudrillard, DNA – life – seen as cloning technology, has become death. “Culture is dead” he says, and it is dishonest to hold onto any of the sources of meaning. Instead, “one should have triumphantly accepted this death.”

In Simulcra it is almost dizzying, and comical, to count the number of cultural forces that Baudrillard sees as dying or coming to an end: democratic values, power itself, perspectival space, meaning, sociality, every dialectic, the myth of the total strike and revolution, the real, the rational, history, value, culture, signs, capital and revolution, totality, the body, and most important of all, May 1968.

And here we come to the glaring contradiction in Baudrillard. This futurist is achingly nostalgic for Paris in May ’68 when it really seemed that the Imagination would come to Power. In the post ’68 era, Baudrillard has no time for the Left since it does a perfectly good job “of doing the work of the Right.” His nostalgia is so deep that he even misses Fascism, because the current “terror” comes from complete neutralization, while Fascism was “at least” violent (capable of violence) and historical, a form of resistance “to something much worse.”

So here we have it – Baudrillard, the theoretician of Virtual Reality, preaches utter abnegation, and at one point in his book “even” Fascism (now inaccessible from our black hole) emerges from his cloud of rage as something somehow preferable to our present state. With Baudrillard and others painting the intellectual background in France over the last generation, it is little wonder that the crypto-fascist Right of Marine Le Pen’s Front National did so well in the last European elections.

Baudrillard’s philosophy is an ideology of anti-praxis, born of utter despair, and that is probably one reason why it strikes a chord with many people who feel crushed by the closed nature of all the political systems that surround them. The response to this complete neutralization and paralysis, however, remains what Marx said long ago: “Philosophers have hitherto interpreted the world in various ways; the point is to change it.”

For Baudrillard, Virtual Reality is actually a frozen, changeless Death. DNA is Death. And Life is Death. Game Over.

IV—Edward Snowden

But neither Jean Baudrillard nor Francis Fukuyama are correct. The Fat Lady hasn’t sung and History has not come to an End.

During the past year, the American whistle-blower Edward Snowden has personally proved that abnegation is wrong by taking enormous risks to fight peacefully against total surveillance and to defend democratic principles. And Snowden’s story is very much that of a person who has grown up in the Virtual World and decided not to accept the prevailing passivity.

Glenn Greenwald, a U.S. investigative reporter living in Brazil, is the person that Snowden reached out to in 2013 in order to leak enormous numbers of documents from the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA) detailing how a branch of government had spied on the personal communications of millions of Americans and other people all over the globe. Greenwald’s book No Place To Hide (Signal, McClelland and Stewart 2014) is mandatory reading for anyone who wants to know what the Virtual Age is really like.

No Place To Hide is about Snowden the man and the electronic espionage he has revealed, but it is his personal story that is most striking. His relative youth really struck Glenn Greenwald when the two first met in Hong Kong to exchange the information that was going to be disclosed. The 29-year-old Snowden was born in North Carolina and because of an illness in his teens, never finished high school. During that time, he educated himself at home over nearly a 5-year period, using the Internet as his own university, and he taught himself the mastery of computers that would be so important to his life. His passage to employment with the NSA and the CIA came about because these agencies suffered labor shortages and sought out alienated, unusual geniuses who have grown up with the Virtual World and are completely at home in it.

Digitilization, computers, and nano-technology mean that a skein of information, public and private, all in binary code, covers the whole globe. Whatever is put into code can be decrypted, so access to these codes makes every single message in the world potentially available for scrutiny, and massive computers make accumulation possible, while searching algorithms can correlate data and metadata effortlessly, without human intervention. At the end of the day, there are servers and clients, and the NSA itself uses business language, calling the government agencies it serves the NSA’s “clients.”

Edward Snowden worked in the system and understood it. He saw through the mystique of technique and clearly visualized the work taking place: state elites are using privileged access to corporate servers to monitor billions of private messages. There is a clear pyramid of power: Government – Corporations—Private Citizens, with the citizenry at the bottom. And at a certain point, Edward Snowden decided to let individuals on the bottom see the real flow of information.

It was Edward Snowden who took the initiative in 2013 to leave the United States, go alone to Hong Kong, and to contact a small number of people: Glenn Greenwald, who worked for the UK paper The Guardian, film-maker Laura Poitras, and through her, Barton Gellman of The Washington Post. Snowden supplied the reporters with enormous numbers of electronic documents that he has since transferred out his hands altogether while he remains in his subsequent Russian exile.

Greenwald broke the Verizon story in the June 6, 2013 edition of The Guardian with a lead paragraph: “The National Secuirty Agency is currently collecting the telephone records of millions of US customers of Verizon, one of America’s largest telecom providers, under a top secret court order issued in April.” The story then went on the describe the secret court document: “The order, a copy of which has been obtained by the Guardian, requires Verizon on an ‘ongoing, daily basis’ to give the NSA information on all telephone calls in its systems both within the US and between the US and other countries.”

On June 6, 2013, the very same day, Snowden’s leaks provided all the information for another extraordinary story written by Laura Poitras and Barton Gellman in The Washington Post: “U.S., British intelligence mining date from nine U.S. Internet companies in broad secret program: The National Security Agency and the FBI are tapping directly into the central servers of nine leading U.S. Internet companies, extracting audio and video chats, photographs, e-mails, documents, and connection logs that enable analysts to track foreign targets, according to a top-secret document obtained by The Washington Post. The program, code-named PRISM, has not been made public until now…Equally unusual is the way the NSA extracts what it wants, according to the document: ‘Collection directly from the servers of these U.S. Service Providers: Microsoft, Yahoo, Google, Facebook, PalTalk, AOL, Skype, YouTube, Apple.’ “

This documentation all came straight from Snowden and one of the the NSA PowerPoint slides he supplied for this story can be seen on P. 110 of No Place To Hide.

Every bit of information originated from Snowden – a single source– and was derived from the electronic replicas of documents that he made available to Greenwald, Poitras, and Gellman. The reporters had to trust him –and the replicas they received.

However, the only hint of Snowden’s agency in the Post story of June 6, came in the very end of the article: “Firsthand experience with these systems and horror at their capabilities, is what drove a career intelligence officer to provide PowerPoint slides about PRISM and supporting materials to The Washington Post in order to expose what he believes to be a gross intrusion on privacy. ‘They quite literally can watch your ideas form as you type,’ the officer said.”

In remarks to Glenn Greenwald, Snowden gives the world a very clear view of his thinking. First, the primordial need to overcome fear: “What keeps a person passive and compliant is fear of repercussions, but once you let go of your attachment to things that don’t ultimately matter – money, career, physical safety – you can overcome that fear.” Snowden told the journalist: “I want to spark a worldwide debate about privacy, Internet freedom, and the dangers of state surveillance. I’m not afraid of what will happen to me. I’ve accepted that my life will probably be over from my doing this. I’m at peace with that. I know it’s the right thing to do.”

Snowden also wrote a letter to the journalists he had contacted: “My sole motive is to inform the public as to that which is done in their name and that which is done against them. The U.S. government, in conspiracy with client states, chiefest among them the Five Eyes [the five countries that are members of the UKUSA Agreement for Signals Intelligence sharing] — the United Kingdom, Canada, Australia, and New Zealand – have inflicted upon the world a system of secret, pervasive surveillance from which there is no refuge.”

Edward Snowden is now very alone. But he acted as an individual through an enhanced sense of his subjectivity and his responsibility.

Snowden has looked through the shroud of Virtual Reality to the actual work done – in our name – so that we, all of us, might assume our own responsibilities to be lucid and clear, and to see that good work is done, the work, not of death, but of life.

Glenn Greenwald puts the alternatives in his own words: “Will the digital age usher in the individual liberation and political freedoms that the Internet is uniquely capable of unleashing? Or will it bring about a system of omnipresent monitoring and control beyond the dreams of even the greatest tyrants of the past?”

Death or Life? The choice is in our hands.