Mexican filmmakers Luis Ernesto Nava and Keisdo Shimabukuro, who are part of the Tres Gatos collective, have devoted the last ten years to understanding and documenting human migrations through Mexico, the largest migration corridor in the world according to the World Bank. After producing thousands of hours of footage and the ground-breaking feature documentary Entre serpientes y escaleras: los desaparecidos [Between Snakes and Ladders: the disappeared], they came up with the idea of going one step further: creating collective murals in the shelters scattered along the route, where the migrants could tell their stories. In their own terms.

These are stories of people escaping the extreme poverty and the violence that has devastated Central America, one of the most neglected and abandoned fronts of the Cold War. The needs of these largely armed, often threatened populations, many of whom are orphaned and hungry, have been ignored not only by their own governments, but also by international organizations as well as the United States. “America” here not only plays the role of a safe-enough, promising-enough land; it is also a key actor in creating the conditions that have led to their desperate desire to escape.

The murals have triggered unimagined reactions, as landmarks for the streaming masses of people who have been forced to abandon their homes.

I was here – with artists

What has been your motivation for documenting these stories?

Luis Ernesto Nava (LEN): Curiosity. It’s owing to curiosity. I believe that you have a responsibility to your findings, and that curiosity implies a commitment to tell the stories you come across, without making any concessions whatsoever. Besides that, personally, as a father I wanted to lead by example rather than avoid doing “dangerous” things because I had a daughter. I decided instead to redouble my efforts and go for it.

Keisdo Shimabukuro (KS): On a personal level, well, my father is a migrant. He fled from Japan to Peru after WW II, and later on he settled in Mexico. When I started doing fieldwork, I felt tremendous empathy towards the people who were coming to Mexico, and that led me to reflect on many things I hadn’t thought much about: I am Mexican, but I look Japanese (or Chinese, or Korean or…), so I can understand how it feels to be discriminated against, to live between two worlds. Mexicans tend to love foreigners, to worship foreigners, as long as they have fair skin and blue eyes.

In the beginning, we thought we would do a documentary about young migrants, about teenagers and children, but soon we realized we couldn’t address that specific topic without talking about gang violence in Central America, the intervention of the US in the region, women, the disappeared, refugees. So here we are.

Part of the existing wall

Why are Central Americans leaving home?

LEN: Poverty and violence, hunger and war. A movement of that scale (almost 2 million people annually, according to the Federal Government[i]) and marked by such perils and hardships can only be explained as a matter of survival.

KS: In Central America, in a context where organized crime is the most viable economic alternative, you can’t advise kids against joining a gang: you are talking about their father, their cousin, their brother, their best friend. Some of them understand that this path is killing them, but there is not much choice. Either you join them or you endure their threats. Or you leave.

LEN: When crime is the most lucrative activity, your father will teach you how to use a weapon as a means of survival, and the cycle (which has replaced the agricultural and production cycles) is really hard to break.

KS: And sometimes you just don’t have a choice – sometimes you’re enlisted by force.

At the border

How did this happen?

LEN: Let’s take El Salvador as an example. Used by the United States as a bulwark against communism from the 1950s until the Chapultepec Peace Accords in 1992, El Salvador was then abandoned with no reconstruction plan. This utter negligence resulted in a fully armed country (if you count everyone over 15 years old) – a country of soldiers – and today the northern triangle of Central America is one of the most violent regions in the world.

If the only difference between guerrilla groups and gangs is the fact that the latter lack an ideology, then we can say that the US preferred, allowed and even encouraged the former soldiers to fight amongst themselves. All of this, by the way, in the face of international indolence.

Migrants on the tracks

So then, how do you explain the fact that the image of the United States as a land of opportunity still holds currency?

LEN: When crossing over to Mexico doesn’t change things much in terms of still being prey to extortion and organized crime, an attack by a gang of rednecks is pretty promising as a worst-case scenario.

KS: As for the US, well, we know that as long as they’ve needed cheap labour, they’ve allowed illegal migrants in.

A victim of human trafficking

When you started addressing the issue of migrants across Mexico 10 years ago, it was a little-known phenomenon. Now it is a recurrent theme even in mainstream media. How do you feel about that?

LEN: Visibility is something that can only be celebrated. It was about time this reality was recognized and acknowledged. However, the phenomenon – actually, a humanitarian tragedy – is treated with some sort of romanticism that, in my opinion, interferes with the need to find a solution. Victimizing migrants and portraying them as heroes conceals the fact that their leaving home is a matter of survival.

It took a while for us to realize that when they say they are “in search of a better life,” they are actually talking about the difference between life and death. A better life means living, period, which explains why they are willing to go through all the difficulties that they know await them.

Mother and child

And what about the Mexican government?

LEN: In 2013, Mexico launched the Plan Frontera Sur, which hardened migration policies. Claiming concern for the safety of the migrants, the plan made it impossible, for instance, for them to ride on the roof of the trains. Ironically (but predictably), such a measure only suppressed the visibility of the phenomenon and made it even harder to monitor the moving populations. The human rights violations, the violence and the kidnappings by human traffickers escalated as these populations had to avoid the known routes and walk through dense jungle.

Is that when you came up with the project for the community murals?

KS: Yes. With five more feature documentaries in progress and after a few life-threatening experiences, we realized we wanted to take further action to boost visibility. So we developed the idea of “marking” the shelters, most of which were run as religious non-profit initiatives whose target populations were decreasing and whose humanitarian role was waning. It was an intuitive experiment, based on our gut feeling and convictions, launched with our own limited resources.

The murals depict a broad spectrum of human migration: survivors of human trafficking, refugees, asylum-seekers, family members of the disappeared, prisoners. Our priority was to provide the tools for people to construct their own personal accounts. We invited in street artists and organized workshops with the express purpose of making this possible, and visible.

LEN: Indeed. The value of the project is that it gives expression to each and every one of the many faces of human migration: it enables different individuals to testify to their experience.

For the people following in their footsteps, they have created a sense of belonging, some sort of rootedness. The murals, partly inspired by cave paintings, work as memorials, as a repository for collective memory, as landmarks for the identity of the migrants; they make it clear for them that there is a lineage, that they are not alone.

KS: Our pride lies in having achieved a direct, non-mediated channel of communication. People interested in issues as diverse as refugees, HIV, human trafficking and internal displacement can learn first-hand how all of these factors intertwine here.

LEN: Through these images, everyone can read the writing (painting) on the wall.

What kind of reactions have the murals prompted?

LEN: Everything that happened after the first mural, I was, in San Luis Potosí (in the centre of the country) where more than 400 people participated, has been surprising.

KS: One local girl, for instance, learned about the shelter through the mural, and wanted to volunteer. Her father, a shoe manufacturer, wouldn’t allow her to go. She asked him to come with her and, while she was talking to the priest, Padre Rubén, the father stayed at the basketball court and started reading the stories at the mural. He not only allowed his daughter to stay, but the day after, he sent a truck with a donation of 300 pairs of shoes for the migrants.

KS + LEN: The basketball court, which most people in the neighbourhood used to avoid out of prejudice and fear, has actually become a popular venue for baptism receptions and all sorts of social interactions and fundraising events. Now the shelter is supported by organizations such as Doctors Without Borders and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, and this support has enabled its organizers to donate the surplus food they receive to their neighbours – who also benefit from the visiting doctors and psychologists – in a remarkably successful example of integration.

Is there a solution?

KS + LEN: Migration is as old as war. By managing a border (as opposed to closing it, or trying to do so, or pretending to try to do so), governments could control the conditions in which the inevitable phenomenon takes place, and choose not to abandon these people to organized crime.

This is a global world, and the nation-state along with its borders has failed, so what were they expecting? People will keep moving in search of resources and survival, towards the most advantageous option, the way they always have. There you have it – the fruits of your free economy!

Civilians sharing food with the migrants

Who is responsible?

KS: One aspect that hasn’t been addressed is the role of family remittances for the Central American countries and Mexico. In the case of Guatemala, these remittances account for around 15% percent of the GDP[ii] and up to 17% in El Salvador.[iii] Actually, the latter’s rulers have designed policies of arraigo, or rootedness, aimed at averting a situation where third- or fourth-generation citiz#_edn2ens of the US stop sending money to their relatives. If you deprived these countries of this income, they would be screwed.

LEN: They would be even more screwed, you mean.

For me, the pivotal issue is people’s attitude towards hypocrisy. If you don’t mind hypocrisy, you will try to exploit the situation or turn it to your advantage. But if you refuse to get caught up in it, you have no choice but to do something – or at least understand.

In that sense, everyone is responsible.

Memorial

[i] This figure was given by Mexican Senator Daniel Ávila Ruiz in 2015. However, the flow of people varies tremendously, as do the figures. According to some sources, the numbers are as low as 150,000 people/year. Such a variation only gives us an inkling of the difficulty of keeping track of these moving populations.

[ii] IDB’s María Luisa Hayem Breve, quoted in: http://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias/2015/05/150526_economia_remesas_boom_america_latina_lf

[iii] Source: http://www.laprensagrafica.com/2015/01/20/el-salvador-recibe-mas-de-us-4200-millones-en-remesas-familiares

Tres Gatos is a multi-disciplinary group committed to promoting human rights and social reconstruction. Documentary filmmakers by accident, the three cats started off simply wanting to understand the phenomenon of migration. Ten years later, there is still no other agenda, which explains why a complete loyalty to facts — no compromise whatsoever — is the leitmotif of all their stories and all their work. All photos are from the Tres Gatos collective.

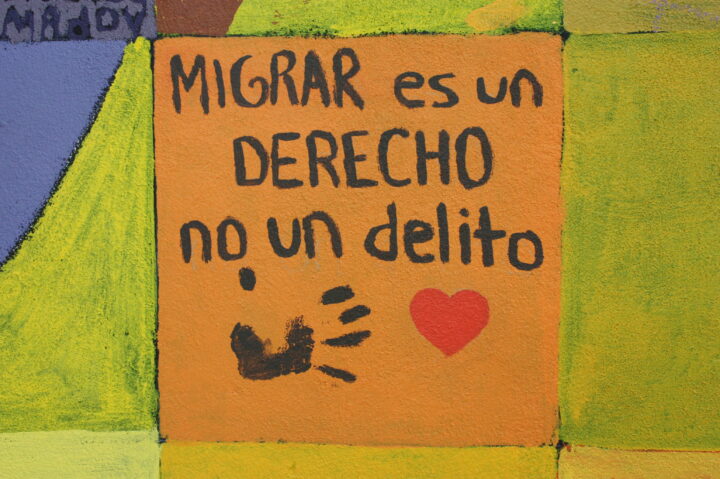

MIGRATING is a RIGHT, not a crime

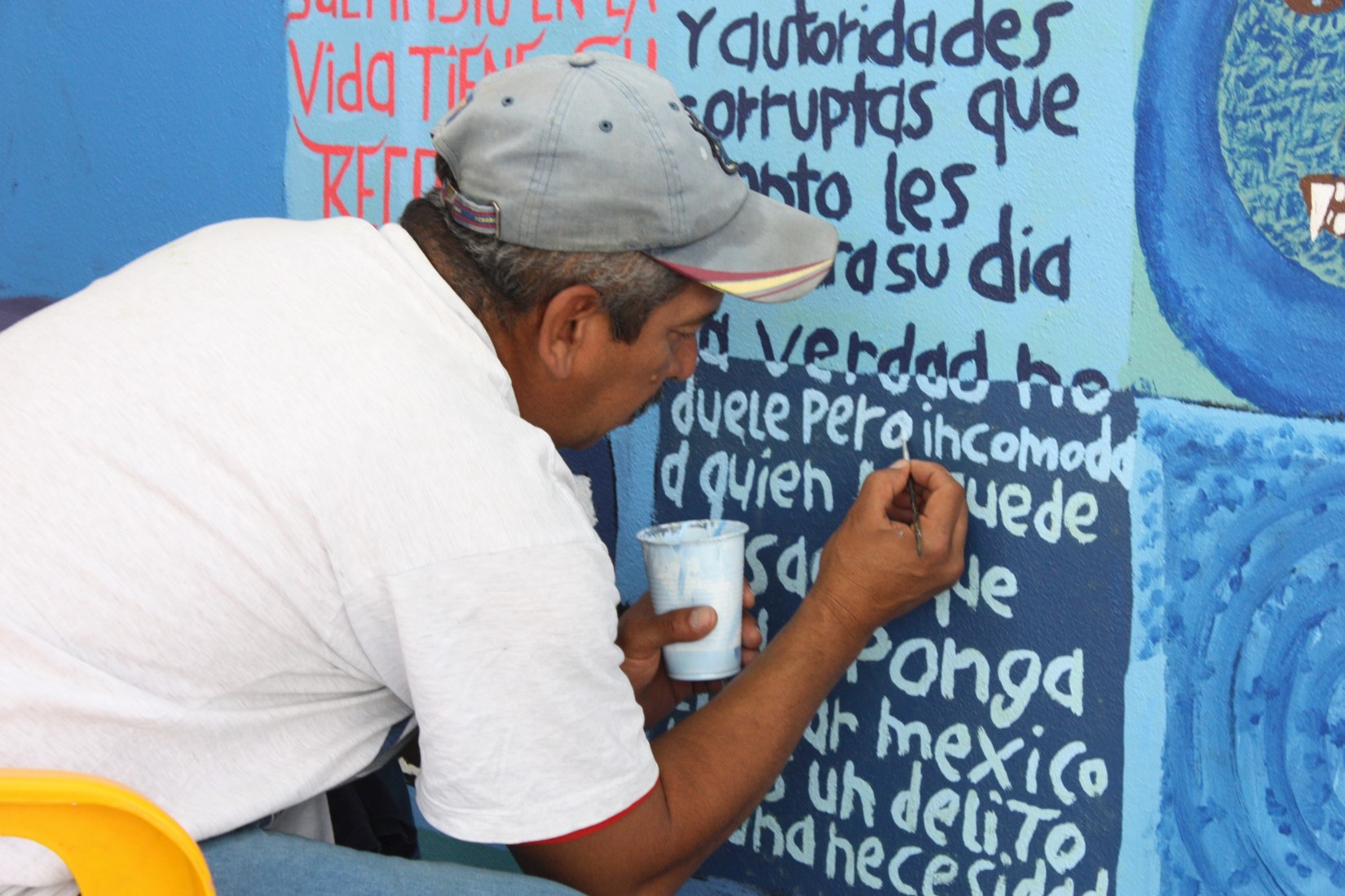

Mural “ I was here ” in progress

Truth doesn’t hurt, but makes those […] uncomfortable

Life is like a game

Life is like a game: there’s more than one chance to advance

Loving children – childcare

May God take good care of them on their journey

Make something extraordinary out of the ordinary

God always lights your way

I stepped out with a lot of pain […], but with faith in God that I will come back soon […], I left in search of the American dream and to reunite with the love of my life.

[fragments of her tree]

I am the migration of those I met

What happens to the migrant, to the traveller, is that upon leaving the known territory, interrelationships with others become more apparent, personal connections need to be co-ordinated…

Happy Mother’s Day to all mothers in the world

Happy Mother’s Day to all mothers in the world. I am here but from here I wish you a happy day. I love you lovely Mama, and I know I am not with you but I always take you with me. I love you Mama. Manuel Rivas. 9/15/2015

I walk towards the United States to help […] my family and look for a future that’s ours […]

Always see the good things in life

[elephant] We always end up arriving where we are awaited

Which of the two lovers will have more [happiness], the one on the road or the one that stays? The one on the road keeps going; the one who stays remains thinking, always, of the road.

Of all the things you do in life, only those that you did with your heart [painted in red] will be memorable.

Caritas Vincit Omina [Love conquers all]

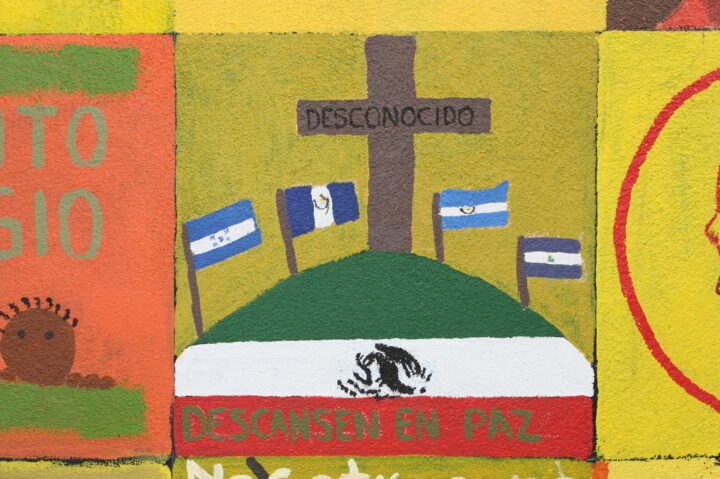

Name unknown, Rest in Peace

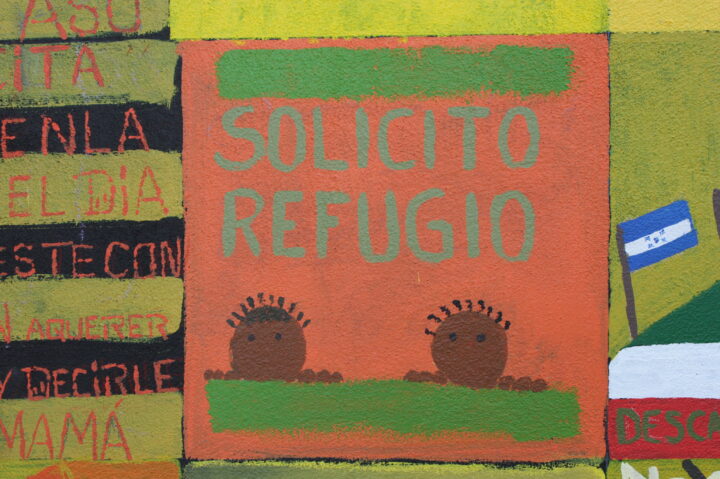

I seek refuge

If there are no borders in the sky

[Mural in Chiapas, on the border with Guatemala]

If there are no borders in the sky…

[Inside the feathers of the quetzal]

My dream is to help my daughters do well

When you arrive, go ahead with confidence

God takes his time, but he never forgets

May God guard your way, 12 years old, Keny

Keep going, don’t give up, 13 years old, Gladis Daniela

Migrant/human being/fighter/overcomer of obstacles, Cristina Aguirre

May nothing on earth stop us

Editorial note (April 10, 2017):

The following video clip by the Tres Gatos collective illustrates the mural project for migrants. It is in Spanish with English subtitles (and can be reset for French subtitles).