Popular Southern folk singer and autodidact guitarist, Matteo Salvatore’s pastoral hell themes weren’t observed from a privileged distance. He hailed from a very poor family that begged and stole vegetables in Puglia, where the Latifondisti exploited landless peasants. These experiences, that inspired his songs, came from a place where peasants had to work nights and were whipped by foremen who forbade talking and sleeping. What he was denouncing was autobiographical, unlike the educated chansonniers who never saw exploitation first hand.

Popular Southern folk singer and autodidact guitarist, Matteo Salvatore’s pastoral hell themes weren’t observed from a privileged distance. He hailed from a very poor family that begged and stole vegetables in Puglia, where the Latifondisti exploited landless peasants. These experiences, that inspired his songs, came from a place where peasants had to work nights and were whipped by foremen who forbade talking and sleeping. What he was denouncing was autobiographical, unlike the educated chansonniers who never saw exploitation first hand.

Salvatore’s father was jailed with the Union Leader Giuseppe Di Vittorio, who rose from agrarian illiteracy to head Italy’s communist union (CGIL); prison time politicized him and his son, Matteo.

Salvatore sang in his Gargano dialect about peasant life which made him an outcast in booming and glossy postwar Italy. He only recorded late in life, such pieces as Evviva la Repubblica (1967), a song about workers and the Republic co-written in jail with his father. In truth, he never used the syntax of the Left. He told stories of the forgotten past. Pasta Nera, (the three qualities or categories of pasta, the third grade is black pasta from burnt fallen wheat kernels), where “a plate of pasta nera is the very least I’d like to eat” and Lu Polverone (1961) recall the dire poverty that time forgot, evoking the malnutrition which took his sister’s life. Salvatore was uprooted from the land by moving to Rome, denaturing his naïveté in his search for fame. Bitter Rice filmmaker Giuseppe De Santis advised him to go back to Puglia to record songs. After this period, he was jailed for the murder of his lover-cum-backup singer in 1973 and banned from la RAI to be forgotten until interest was revived by the Big Night (1996) soundtrack and Vinicio Capossela before Salvatore’s death in 2005.

Many of the absolute protest songs that never went mainstream from the South were sung in dialect. For example there are those in Sardinian, like the songs of Franco Madau, Enea Danese and N.G. Rubanu which protested the NATO European nations’ and American occupation of the island, and the general militarism of the Italian military complex that destroyed ancestral transhumance paths that shepherds used for their herds. The worst of the military occupation would be uncovered much later: the depleted uranium residue causing Balkan-Quirra Syndrome from the missile launching area of the 1960s.

Cantacronache (Storytellers) was a collective founded in Turin in 1957 by Fausto Amodei, composer Sergio Liberovici (along with his wife Margot), Michele Straniero and Emilio Jona. It was the re-emergence of the Italian protest movement by replicating revolutionary chants, although the inspiration for new material came from elsewhere – from the likes of Hanns Eisler, Bertolt Brecht, the half-Italian Georges Brassens and even added Yiddish sonority (Liberovici’s father came from Eastern Europe). Reacting to the San Remo Festival of songs, they rejected superficial songs popular in the 1950s such as caroselli and canzonette. Their j’accuse in Evadere all’evasione, (Escaping the escapism), was about Italy learning to love escapist songs in an effort to forget wartime experiences. Italo Calvino collaborated with the collective and wrote about his wartime partisan experience in Oltre il ponte (1958) and Canzone Triste (1958).

Ero un consumatore, (I used to be a Consumer), (1960), is a prophetic song by Amodei about being a good citizen, voting for whoever is in power until his life is disrupted by his love for salad and the adulterated olive oil which wrecks his kidneys and guts. He eliminates lards and fats from his diet but eats poultry with hormones which denature the female chicken that has become a capon, and those hormones, in turn, change the narrator’s sex. Then, real estate speculation results in shoddy building materials being used in the place where he resides, and the replacement of cement with chalk results in his apartment collapsing onto him. After his wife has left him homeless, he goes to church but the candles and holy water, they too, are adulterated with profane water and his soul is forever damned.

The group played in various case dei popoli and was disbanded in 1962, but their work led to Nuovo Canzonieri Italiano.

Inheritors of the folk genre

Inheritors of this folk genre included Ivan della Mea, who revisited O Cara Moglie (1966) and Roman Giovanna Marini, whose Il treno per Reggio Calabria (1973) is about workers from the North going to the South by train, (and by ship from Genoa), to support fellow strikers in Reggio Calabria to be confronted by neo-fascists. Roman Paolo Pietroangeli’s Contessa (1966), became the Italian May 1968 anthem, and was penned after overhearing a conversation, at a swank caffè, between a Roman borghese and a Countess.

“Four ignoranti went on strike demanding higher wages, those four straccioni (ragamuffins) screaming that they are exploited, saying that when the police came in, blood was all over the cortile (courtyard) and door, who knows how much time it will take to clean it all up… Do you know, Contessa, that gentaglia (riffraff) occupying… that the worker wants his son to become a doctor, can you think of what could come out from a place with no morals?”

Honey-voiced Claudio Lolli sings about the old small petty bourgeoisie in Borghesia (1972), who are:

“happy when a thief dies or a prostitute gets arrested…you are satisfied when others are at a loss but you hold your monies tightly. You relish it when an abnormal gets treated as a criminal, you’d lock up all the gypsies and intellectuals in mental hospitals. You love order and discipline, adore your police, except when it has to investigate fraudulent bankruptcy. You know how to steal with discretion and moderation, altering balance sheets, invoices and commissions. You know how to lie with cynicism and cowardice….You could have many misfortunes befall on you, an artist daughter, or not to have a businessman for a son, or worse yet, have a communist son. {The chorus} I do not know if you cause me anger, pity, schifo (disgust) or malinconia.”

In Lolli’s Ho visto anche zingari felici (1976) album, (I have also seen Gypsies Happy), Agosto is about the Italicus train bombing by neo-fascist extra-parliamentary groups and the hypocritical politicians who show up at such mediatised funerals in Piazza, Bella Piazza.

Gualtiero Bertelli, a member of Nuovo Canzoniere Italiano, wrote Nina ti ricordi (1966, recorded later) in Venetian dialect, about the Catholic sexual mores of a young working class couple where “loving is a luxury only few can afford” and in the meantime Nina ends up pregnant and her boyfriend is unemployed.

Canzoniere delle Lame, was anointed by the Italian Communist Party. It was founded in Bologna in 1967 by Gianfranco Ginastri with female vocalist, Janna Carioli, and mostly toured nationally and internationally, singing international protest canon.

Canzoniere Pisano, in 1966 was founded by Pino Masi, who was associated with extra-parliamentary groups on the Left until his own j’accuse about the ‘68 generation in 1975.

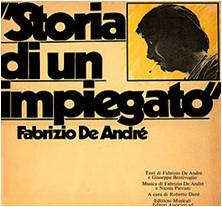

Fabrizio De Andrè started his career in the early sixties with anti-war song, La Guerra di Piero (1963), which only became a hit in 1968. His repertoire includes the anticlerical album, La Buona Novella (1970), with Il Testamento di Tito which wasn’t received well by the protest generation while his most anticlerical songs are found on other albums. His themes revolve around stories of emigration and marginalization; about people such as drug addicts, fishermen, the real-life prostitute of Genoa in his hit, Bocca di Rosa (1967) and the street where the transgendered live in Via Campo (1967). In his last album, Anime Salve (1996), Kosovar, Muslim gypsies are his focus in Khorakanè and he revisits the transgendered in Princesa.

De André’s most political concept album, Storia di un Impiegiato (1973), with the emblematic song Canzone del Maggio,(May Song), indicts an impiegato (office worker) who is faced with the choice to do nothing or join the demonstrations with the leitmotif, “For however much you think you are absolved, you were always involved.” Due to censorship, that line only exists in the censored version. The censured, unreleased version of Canzone del Maggio is as follows:

“Even if our May was made without your courage. If the fear of looking, made you look onto the ground. You decided in haste, that it wasn’t your war, you didn’t stop time, you just made it lose time. You told yourselves, that nothing will happen, the factories will re-open, they’ll arrest a few students. You were convinced it was a game that only few played, you were the instrument that made us lose lots of time. You let the clubbing professionals liberate you of us lowlifes, hooligans and rebels, leaving us in good faith bleeding on sidewalks, even though now you don’t care — but that night you were there. If in your neighbourhoods, everything is the same as yesterday, and even the rocks in your streets remained in their places, you took the good news of the ‘truth’ from your papers, so now there remains no more arguments to let us lose time. We know very well about your false progress, your commandment, ‘Love consumption like yourself’ and if you only observed, just to absolve those who fired at us, we will come to your doors again, we will scream louder, you can’t stop time, you only let it lose time.”

Il Bombarolo, (The Bomber), is a first-person account of an office worker’s evolution into a hapless terrorist – his mission is to hit the parliament. It is revealed he is more concerned by his personal love drama – his girlfriend who rebuffs and ridicules him in the papers only after his claim to fame. One wonders if Feltrinelli’s fucked up attempt and death in 1972 inspired these lines: “In descending the stairs, I heed more attention because it would be unforgivable to execute myself underneath my door’s threshold on the very day I would be condemned or given amnesty.”

Giorgio Gaber is an anomaly because he was decidedly anti-politics, criticizing the Italian Communist Party, Christian Democrats, Radical Party and Socialist Party. He refutes being an Anarchist, in one of his spoken word acts, “Anarchist? I am a shit. Anarchists love humanity. I like to view humanity from above.” In his Qualcuno era comunista (1991), (Someone used to be a communist), spoken act, he lists all the reasons one became a communist in Italy, some for convenience, some by conviction, some because of the party system in Italy, some after state terrorism, some inherited their commitment, some became engaged because it was trendy. In Destra/Sinistra (1995), he asks what is the Right? and what is the Left? “The response from the masses is Left, the soft compliance is Right, I am sure the bastard is Left while I am sure the figlio di puttana is Right…We often blame history but the fault is ours. It is evident. People are hardly serious when they talk about Left or Right.”

Se fossi Dio (1980), (If I were God), is an attack on every political party, so much so it was banned on radio and no recording house wanted to record it. Gaber mocks the President, who consoles grieving mothers during the “Years of Lead” and calls journalists cannibalistic necrophiles, making money off of terrorism’s dead. Gaber mentions the oily anointed Christian Democrats, grey bureaucrats or career politicians and communists get referred to as picci (play on PCI’s acronym)…The libertarian Radical Party gets the worst of it: “I don’t know who gave you compagni (comrades)but you are disqualified; climbing on the winning side and you’ll ask another annoying referendum about where dogs should piss.” The Socialist Party gets referred to as carnations, making alliances with parties on the Right, Centre and Left. For the Red Brigades, their actions caused the masses to pity the police and “removed my taste to get angry with the State.”

Il Conformista (1997-2000) is about the opportunist who changes teams in the postwar period, the history of the average Italian:

“I am a new man, so new that I am no longer a Fascist. I am sensitive and an altruist. An Orientalist. In the past, I used to be a 68er. Just recently, an environmentalist, like everyone else a few years ago, I got caught up in the euphoria, a Socialist. I am a new man, literally that I am a progressive but I am also Libertarian, anti-racist, animal right-ist, I am no longer welfare(ist) but recently, I am countercurrent , I am a Federalist (referring to Northern League’s separatist version ). The Conformist is always on the right side. He always has the right answers in his head. He is a concentrate of opinions because he always has three newspapers under his arms…He is a round man, who moves without consistency, he trains to slide into the sea of the majority. At night, he dreams other people’s dreams. I am a new man, with women I have extraordinary relations, I am a feminist. I am willing and able, an optimist. Europeanist. I never raise my voice, I am a pacifist. I was a Marxist-Leninist after a while I found myself to be a Cattocomunista (Catholic Commie, used as insult). I must say nowadays he resembles many of us. I am a new man, it shows at first sight that I am the new Conformist.”

Un’idea in Gaber’s album, Un dialogo tra impegnato e un non lo so (1972), (A dialogue between an activist and an I-Don’t-Know), “An idea, a concept, remains an idea until it is just an abstraction. If I could eat my idea, I would have made my own revolution.”

In Libertà (1972) he tells us, “Freedom is not found atop of a tree, it is participation” which could mean many things. Unfortunately for Gaber, much to his dismay, his wife, Ombretta Colli, participated and became a Berlusconi politician. Si può (1976, 1992, 2001), (It can be done), reworked earlier versions to fit the age of Berlusconi, about freedom of expression, “freedom to criticize from the outside, the government, ignoble television shows that slap each other like coglioni. We can do caricatures, satire, even write a verse about the Pope, re-sing Faccetta Nera…with all the freedom you got, you want even freedom to think?” The original 1976 version had “you want even the freedom to change?”

Non mi sento Italiano (2003), posthumously released, is about not feeling Italian with the chorus “but fortunately/unfortunately, I am” but ends with positive stereotypes.

“Sorry, Mr. President, this patria I do not know what it is? I don’t see the need for a national anthem. In terms of soccer players who may not know it, maybe it is comes from a sense of scruples. Besides a few heroes…, I see no reason to be proud. Sorry President, I have in mind the fanaticism of black shirts in the time of fascism. Unfortunately for foreigners we’re only spaghetti and mandolins, to which I get angry, and say I am proud and boastful and throw the Renaissance in their faces. This beautiful country, maybe it isn’t the wisest, and has confused ideas but if I were born elsewhere, it could be worse.”

Francesco DeGregori’s Viva Italia (1979) begins with the words, “Italia Liberata”, (Freed Italy), and mentions, “Italy assassinated by cement, Italy that was robbed, that was betrayed, Italy that isn’t afraid, forgotten Italy and Italy that needs to be forgotten, that works, despairs.” He cites historical tragedies such as the Piazza Fontana bombing and ends with the poetic “Italia che resiste” (Italy that resists), referring to the ideals of the Resistance as well as the eternal political woes that define Italy. He was famously interrogated and tried on stage at his own concert in Milan in 1976, accused of making money and selling records by exploiting leftist themes decried by the extra-parliamentary Left audience members. (Gaber uses this “sell records” line in Qualcuno era un comunista monologue in a live performance).

Rino Gaetano’s most famous song, Il cielo è sempre più blu, (The sky is forever still blue), is not much of a protest song but a litany of mundane everyday things that describe 1970s Italy. “(he) who steals pensions, (he) who has a short memory, he who dies at work.” The lyrics could be applicable to today’s Italy. His line, referring to terrorism, the state which hid the actual masterminds, was censored and he was forced to change lines that alluded to secret services’ involvement in terrorism “(he) who throws a bomb, (he) who hides the hand, who sings Baglioni, who breaks coglioni “- to- “(he) who was fined, who hates terroni (Southerners), who reads Prévert, sings Baglioni.” His overtly political Nun te Reggae più, is a play on words, non regge più, (it doesn’t hold up anymore), was censored for mentioning current issues and names; it was also changed for the San Remo Festival. A song about backbreaking Fiat assembly worker and his worker alienation in Operaio del Fiat della 1100 (1974) where the automobile worker develops a deep hatred for cars.

Michele Straniero, a former Cantacronache, also dedicated a song to La Madonna della Fiat in 1979.

At the precipice of the hedonistic 1980s, a few politicized acts stand out except for the punk groups such as Bologna’s Skiantos, who were associated with Movimento’77, intent to revive the ’68 movement. CCCP from Red Emilia, where its legacy has been overshadowed by the frontman who renounced his Soviet-loving past to swinging to the far opposite of the ideological pole; he became a born-again Catholic associated with the Berlusconi / pseudo religious business lobby from Lombardia known as Communione e Libertà, voting for the Right and the Northern League. He now supports Zionism when he used to sing about the Intifada.

But the frontrunners of Italian genre, Combat Folk, were Gang from the Marche region, formed in the 1980s, who wrote anti-Craxi and Anti-Berlusconi songs such as La corte dei miracoli (1994). La pianura dei Sette Fratelli (1995) based on the seven Cervi partisan brothers assassinated by fascists. Gang dedicated the Il Seme e la speranza album to the Resistance with their song, 4 Maggio 1944 – in memoria (2006) commemorating a massacre, in which 63 people died, including a family of peasants for feeding partisans. In the 1990s, Modena City Ramblers took on the Combat Folk torch while imbuing their music with the sounds of Irish wind instruments, klezmer horns and using the Modenese dialect for the protest Resistance song canon in their 2005 album, Appunti Partigiani.

99 Posse: Neapolitan playing cards motif

During that same period, a wave of political outfits were led by trip-hopping anarchists from Naples’ centri sociali (social centres) such as 99 Posse (Italians love Native American symbols of resistance; DeAndré also has such imagery on one album cover). The singer, ‘O ZULU was beaten by fascist youth last June while on tour. Their song, Pagherete Caro (1993) (You’ll Pay Dearly), was about the Northern League. Rafaniello (1992) would attack the various neo-ex-Communist Party leaders, by comparing recent politicians to radishes, red on the outside but white on the inside; “but we like tomatoes” (pummarola being the Neapolitan word and a cultural symbol).

Caparezza is a hiphop rapper from the same area as Matteo Salvatore. His themes range from workplace deaths to Italian politics. Ghigliotina (2011),(the Guillotine), asserts that the revolution is against political parties – the Radical Party leader’s endless hunger strikes and Berlusconi female politicians’ plastic “tits”. Legalize the Premier (2011) is about Berlusconi’s laws to save him from trials and prison with infusion of reggae, another genre politicized Italians love. Another ode to the Northern League, Inno Verdano (2006), (the Green Hymn), refers to appropriation of Verdi’s Va Pensiero for imaginary Padania’s national anthem as well as a nod to their Green Shirts. It has catchy hooks and lines such as, “I want a secessionist Padania, secessionist flag, secessionist girlfriend,” and the latter refers to Miss Padania dating the party founder’s son.

Eroe (2008) is about everyday working class heroes, “I am a hero because I fight every hour.” Vieni ballare a Puglia (2008), (Come Dance in Puglia) denounces the touristy sunny vision of Puglia that emerged recently while the steel plant Ilva’s polluting factory kills its workers and citizens in Taranto and the tomato industry in the South has been exploiting immigrants. The singer Al Bano introduces the song along with whitewashed Trulli imagery, the cultural symbol of Puglia, adds to Caparezza’s subversion of traditional music and dance, la pizzica.

Punkreas’ video was censored for Polenta e Kebab (2012), whereby polenta is the cultural food signifier of the North and the kebabs, the food the Northern League politicians wanted to ban: “Strange green creatures, against terroni (Southerners)… fennels (derogatory term for gays), gypsies, black bastards…The real Padania miracle, ‘Ndraganeta (Calabrian Mafia) in Milan.” A Calabrian group called Kalafro, again a nod to black empowerment, also has songs dedicated to Northern League’s green shirts in Camicie Verde and brigands in Resistenza Sonora (2011).

Many impoverished anonymous composers of canti popolari got plagiarized by other anonymous composers, and we could say that those who “sampled” were poor with no formal knowledge of music, and that they had to steal melodies. Some songs were interchangeably used by both fascists and communists. And anonymous was indeed a woman, an agrarian one, since le mondine, those rice weeders, invented songs in the rice paddies to be later “remixed” by ideological males.

Perhaps being a country made of facile and contentious complainers and subservient people with intermittent bouts of civil disobedience, it has been natural for Italy to have many legitimate grievances to denounce and protest against in a country born, and re-born, from conflict, hegemony and conspiracies.