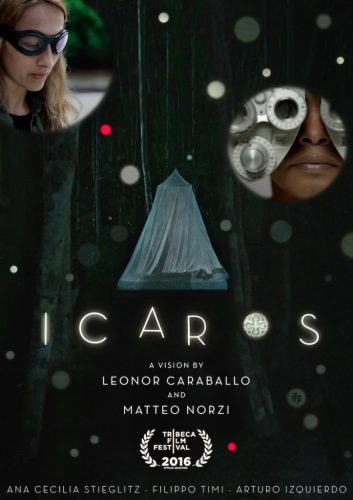

Co-directed by Leonor Caraballo: (1974 – 2015) and Matteo Norzi

Produced by Abou Farman

Editor: Èlia Gasull Balada

Starring: Ana Cecilia Stieglitz, Filippo Timi, Arturo Izquierdo, Taylor Marie Milton, Guillermo Arévalo

Duration: 91 minutes

“Founded by Abou Farman, Matteo Norzi and Leonor Caraballo in 2013, Conibo Productions aims to promote the creativity and knowledge of the Amazonian Shipibo Conibo communities through a range of media, including cinema, visual arts, music, performance and plant medicine.”

[The co-director died of metastatic breast cancer during the filming, leaving her widower spouse to complete the film.]

A shaman enveloped by the hot Peruvian forest blows smoke in the direction of the dead white woman whose life we see in a circle edit reminiscent of Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Conformist (1970).

On the face of it, Icaros: A Vision brings together two pathologies, a shaman’s developing blindness and a rich Westerner’s spreading cancer. Both the blindness and the cancer will be victorious, in spite of a healing forest.

For money-making scientists, the forest is the primary site for gaining an understanding of tribal methods. These giant pharmas use the trial-and-error labour of our ancestors to make hyper-expensive medicines that they dangle in front of people who cannot afford them. This pharmaceutical truth is presented in a surreal nine-second sequence of brilliantly calculated neo-experimental film. A forest citizen steps into an elevator (circa 287 BC). The steel doors open, not onto carpets in an institutional hallway but into the forest greenery. Spectrally, this citizen walks into the pharmacy called the forest.

In the main site, in the forest, a child moves her hand in arc-like fashion across a gauze curtain on the window of a wooden building where the guests have their meals. Her hand sweeps us into an evening with a candlelit toad croaking to a god inside a white porcelain toilet bowl, which, due to the camera angle, looks like an inverted Taj Mahal (1632-53).

Brown men sit behind desks signing in a few international guests.

I watch the actors consume Ayahuasca. I get pseudo-high enough to like the Westerners who now appear logical and reasonable.

A man’s leg ends in a cloven hoof; a rat looks up into squeaky clouds of patagium (bat wing membranes); a burning leaf becomes a steel elevator. The light-filled gauze tent sits in a windless forest as a Shipibo shaman with a Beatles haircut (I wonder where the Beatles got it from) exhales more smoke.

And more perfidious illusions: birds with bladder-in-the-throat songs, bats flapping the forest air into a dark resin, singing human voices are layered with electronic beeps and images taken from Magnetic Resonance Image machines (1971). This audiovisual mix is art. The film’s experimental sections are so resplendent that one almost forgets the two pathologies. A floating blue ball follows a secondary actor; the helium (1868) within it communicates with the capillary action (1660) in the trees. The international guests, looking for solutions for personal problems, connect with the veins of awakened trees.

Leonor Caraballo and Matteo Norzi have performed edits that have a high poetic yield. Although the two pathologies provide the basis for the film’s experimental transportations, one is left to wonder which one is more pertinent – the pathologies or the experimental film sections. Perhaps this is the strength of the work: that these two aspects of the film – the semi-detached experimental sections and the pathologies – overlap, connect and overlap again without decorative or superficial subplots. Yet despite this strategic, necessary complexity, I am unable to react emotionally. Oliver Twist (1948) allows one to respond emotionally, while Citizen Kane (1941) has cold, machine-like characters. Icaros: A Vision is super cold.

Ana Cecilia Stieglitz acts with a rangeless physiognomy that is not bereft of emotion, but pregnant with death. Arturo Izquierdo (the man who is going blind) conveys a similar flatness. A man vomits into a bucket. One wishes he’d vomit from the cradle to the grave, but somehow the directors provoke compassion. A woman pukes into a red Walmartian bucket (1950). She is clearing her body to receive the transportation, while in my head, I aerial drone over Marx’s grave in the forest of Highgate, London.

The cancer story is Leonor Caraballo’s life story presented in the shape of a Heliacus implexus. Surrealism licenses me to speak into the shell:

Leo, you’re dead but I’m talking to you. I’m supposed to come to New York to see your film on the 19th of May 2017 at a cinema located at:

40.7423° North

74.0062° West

But I can’t come due to Donald Trump letting the border-control people off the leash. I am scared to cross the US border. Something went wrong since your departure.

Leo, did you shoot your film here:

12.0433° South

77.0283° West?

Leo, you left when the film was halfway done. Now, Mateo Norzi and your widower-producer, Abouali Farmanfarmaian, have finished your de-sentimentalization of death. Abouali has been looking for your meridians.

Leo used cancer like a painter uses paint. She and Abouali Farmanfarmaian made competent, cancer-connected works within four years (cf. Life in America: https://montrealserai.com/article/life-in-america/.

The story of the characters oscillates between with the experimental film sections that consist of Rorschachian splatterings, colourful blimp-pitty-blimp radar-ee scans, light-filled lines bending to the gravity of a cancered breast that looks like a negative image of Olympus Mons, a large shield volcano on Mars.

Face down on an MRI sliding bed, the protagonist is graduated in and out of a tight white tube. The machine’s latitudinal red marker lines are superimposed over the old forest in the experimental sections while, from the dark forest, we hear a sound fade-up of the shamans singing. Their voice-music, like a prehistoric, super slowed-down Morse-code (1836) transmission, fills the forest night. Colourful animated dots recede into the white gauze tent. MRI images, eye examination charts, mix with irritated wire-cobras; this complex of images forecast the bad news.

An optometrist tells the shaman: You’re going to go blind. The directors make us aware that today you can see a bat on a summer evening; tomorrow, you’ll just hear its wings. Echolocation. Waves bouncing off cloven hooves. Tomorrow, your cancer will be victorious. The experimental sections connect with the protagonists’ lives.

The directors do not address the death-sadness index. However, they do show: death shorn of its Paseo de los Tristes (1609); death, shorn of its chaplains in the bereavement industry.

We see the phoropter masking the shaman’s face. An eye examination chart (Snellen chart, 1861) stands erected in a large sunbaked area that has beautiful mud walls. Black figures, possibly culturally coded, are on this white board. A shaman throws a stone at the board; these black figures fly off skyward. These images are followed by subaqueous views of river dolphins swimming in brackish water. The fish are captured in nets, and a screen-within-a-screen sequence shows their eyes being pulled out for profit. Westerners. Forest. Shamans. River. Profit.

Icaros: A Vision centripetally pulls us into these hemispheric frustrations with a faintly implied class awareness. Economically poor shamans in need of money have to supply rich tourists the commodity of Relief. The film far surpasses an illustration of supply and demand.

The directors have given us such a shockingly controlled sound mixture bonded to a visual feast that one waits for part two.