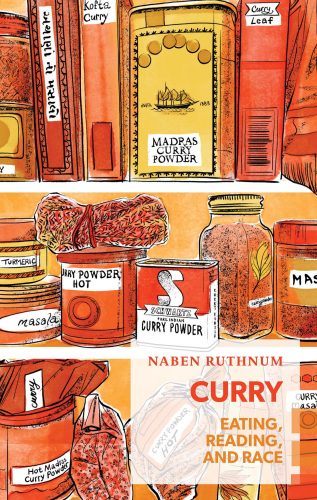

Curry: Eating, Reading and Race by Naben Ruthnum

Coach House Books, Exploded Views Series, 2017.

When it comes to word association, some words are more potent than others. Like curry.

“Curry isn’t real . . . . It’s a leaf, a process, a certain kind of gravy with uncertain ingredients surrounding a starring meat or vegetable . . . but it’s also an Indian fairy tale composed of cooks, Indians, émigrés, colonists, eaters, readers, and writers.

Fuck off, my ideal reader might be saying right now. Of course it’s real, it was on my plate and soaking into your naan last night. And you’d be right, sort of. But even if the flavour is real, and delicious, it’s also become a crucial element of how the story of South Asian cultural identity is told . . . .”

So begins Toronto-based writer Naben Ruthnum’s dazzling and long essay, which successfully marries erudite, penetrating socio-cultural and literary analysis with a personal exploration of eating, reading and race.

Ruthnum’s parents immigrated to Canada from Mauritius. Trying to grow up “Canadian” in Kelowna, British Columbia, he visited Mauritius just once, at age 9. While he proudly claimed the “curry” made at his home as authentic and defended it as part of his cultural identity, he rejected “curry books.” These were books authored by people with Indian names, with stereotypical fonts and images on their covers.

“There was an acceptable authenticity in what we ate, one that I felt counter to the books with various brown hands, red fabrics, clutched mangoes, and shielded faces that turned up on our shelves . . . .”

In the book’s first section, “Eating,” Ruthnum deconstructs food writing, including recipe books, bringing in his own experiences of making and eating curries. Myth making and romanticism abound here, with memories of grandmothers’ and mothers’ kitchens. But cooking “authentic family recipes” comes hard to the second generation, given the imprecision of the recipes handed down from relatives! And some then resort to buying cookbooks by Indo-British cooking celebrity, Madhur Jaffrey.

Ruthnum acknowledges briefly that Indian food is as hard to define and encompass as curry, given the incredible regional variety. He writes that myth making and attempts to pin down authenticity expanded further when it came to curry books. Through the 1970s and 80s, “South Asian literature” became mainstream, and the “disconnected-family/roots-rediscovery page-turner” became a sub-genre within that larger genre. These books, both fiction and nonfiction, typically contrasted “the pure-if-backward East with the corrupt-but-free West,” and were largely “nostalgic, authenticity-seeking reconciliation-of-present-with past family narratives.”

There are of course more subtle and nuanced curry books, very much part of great South Asian literature. Ruthnum details a number of authors and books of this kind. But since the somewhat problematic success of curry books, which after all pander to stereotypical views rather than exploring new ground, South Asian writers in the diaspora started getting a strong message on what kind of book they should write. There is a growing Western and diaspora audience for such books, and the sub-genre includes Western writers like Elizabeth Gilbert (Eat, Pray Love).

There are ironic and lighter moments in the book like Pakistani-American novelist Soniah Kamal’s “mango” dilemma. Not wanting to pander to an “orientalist Western gaze,” she mulls over the issue, finally allowing her characters to eat the fruit in a summer scene set in Pakistan! Tropes reflect real circumstances, says Ruthnum, who feels some sympathy for the affirmation of alienation that makes (some) readers turn to curry books.

Ruthnum’s last chapter on race is his most powerful. Here he deconstructs many homogenized, sanitized, “banalized” concepts and realities, including the South Asian diaspora:

“A poisonous, crucial element of this imposed expectation is that brown people and their books should look back, into a past and a place that may never have existed.”

Despite all obstacles, Ruthnum demands multiple narratives spanning many genres from culture (not just literature) about and by brown people, and finds South Asian stand-up comics already taking this on.

I took courage from these words:

“The realities of racism and the white majority dominance of life in the West defines how brown people are seen, how they must act, and what they are allowed to achieve – but this doesn’t need to limit our imagination of ourselves, or lessen the distinctiveness and individual nature of experience, especially as expressed in art…”

He has set aside his first novel, with some curry book connotations, for now, and will be publishing a thriller instead (Find You in the Dark) in 2018. The book will be published under the pseudonym Nathan Ripley. A copout? In “Curry” he offers a convincing argument for why he chooses to go this route.