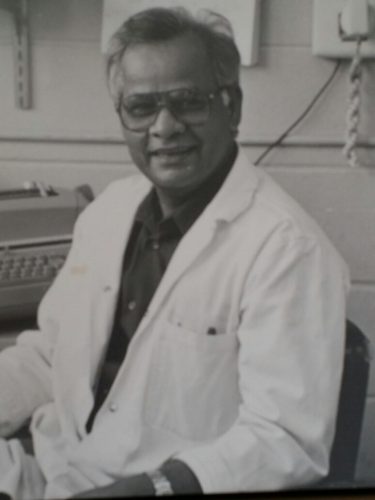

August 23, 1929 – March 22, 2015

Dr. Daya Ram Varma, died Sunday March 22, 2015, at his home in St. John’s surrounded by loving family and friends.

Daya was born in a small village called Narion in India to proud parents, the late Sampati and Matabadal Chowdhary. Starting at a one-room primary school in his village, he walked 8 Km everyday to school. Later on, he came to be known as the boy who came back home from school on cow carts, doing his homework. He went on to receive MBBS and MD degrees with honours from the prestigious King George Medical College in Lucknow. He came to Canada to study in 1959 and received his PhD in Pharmacology from McGill University in 1961. He rose through the academic ranks, and then continued to work through a post-retirement appointment until 2007. He was made a professor emeritus in 2009.

Daya was a lifelong activist dedicated to equality, justice, and peace. He was a secularist and a socialist who applied his intellect towards social causes. He was featured in many documentary films such as Bhopal: Search for Justice, which chronicled his compelling findings as a way to find justice for victims of the Bhopal disaster (1984). He authored two books on the history of medicine, over 225 scientific papers, and a large number of political articles published in a range of prestigious journals. Never daunted, he compiled the March issue of International South Asia Forum (INSAF) bulletin during the last stages of his illness.

Daya founded, supported, or influenced many progressive organizations such as the Indian Peoples Association in North America, South Asia Research and Resource Center (CERAS) , Kabir Cultural Center, the South Asia Womens’ Community Center, Teesri Duniya Theatre, and many others. In particular, he championed the cause of peace and harmony between India and Pakistan.

Daya came from a small village in India and his life ended in a small city in Canada.

Below are two short essays written by Montreal Serai Editors, Maya Khankhoje and Rana Bose on his passing. Also, we have included links to an interview of Daya Varma done several years ago and a review of his first book by Maya Khankhoje.

Daya Ram Varma: Compassion God Shield.

by Maya Khankhoje

Born with a name like that it is no wonder that Daya turned out to be the man he was, a man of infinite compassion who devoted a large chunk of his life to shielding the weak from the onslaughts of greedy corporations. He never let the world forget Union Carbide and its responsibility for the damage it caused to present and future generations. But he did not invoke God’s help for this task because the word God did not form part of his vocabulary. Daya’s vocabulary was that of science and rationality tempered by a radical humanism that brooked no compromise with the truth.

I had the privilege of being a neighbour of Daya and his companion Shree for many years when they lived in Montreal. Their home was my home away from home. When they moved to Newfoundland his friends, including myself of course, felt bereft. And we also worried, worried about Daya feeling lonely away from his old friends and the park where he walked Mischief, his beloved dog. Worried about his getting bored away from his lab and meetings with comrades. Worried about his feeling redundant after retirement. But we seriously underestimated him.

The house in St. John’s where he lived was located near an even more magnificent park and the friends he left behind were, not replaced, but complemented with new friends he and Shree quickly acquired in their new surroundings.

Now that he has truly left us, I feel truly bereft, but I shall remember him in anecdotes illustrated by an image of an impish smile that soon turns into laughter.

Once I was walking Mischief in the park while Daya was away in India. Missing Daya, Mischief did a sit-down strike on me and I couldn’t get this gentle golden lab to get up and go back home. I tried tempting him with the word “biscuit,” “food, ” “home” to no avail. When I finally said “Daya” his ears perked up, he quickly sprang to his feet and followed me all the way home while I kept calling out Daya’s name.

Friends, when we feel that the struggle is hard and futile, all we have to do is invoke Daya’s name for a shot of encouragement.

If there is another Daya Varma…….

by Rana Bose

If there is another Daya Varma, please stand up. And nobody shall. The room and the world will remain silent and still.

As a scientist, researcher, teacher, rationalist, continuously evolving Marxist and Socialist, Daya never looked back. He looked beyond the landscape and horizon and came up often with the most perplexing questions and proposed the most complex paradigms. His last paper, which is in the process of being edited now, says that Poverty is actually a Disease. It is practically a socially engineered condition, which demonstrates symptoms and needs prophylaxis. There aren’t many MD PhDs in the world who think of social change while delving into pharmacokinetics. He asked me to take a look at the paper and called me a couple of days later to ask if I had. I had already reviewed it and passed it back on to him. But he had not checked his emails. His voice was failing. He simply said that he was very happy to see me and Lisa, a few days earlier. “I don’t have much time left,” he said.

In the squally, windswept easternmost rock face of Canada, we looked out at the sea at Signal Hill in Newfoundland with his wife Dr. Shree Mulay and it struck me there and then that an era in our lives was coming to an end.

As a biomedical engineer, I came to Montreal, some thirty eight years ago from the United States. It was the time of Mrs. Gandhi’s Emergency rule. Night had descended on India like a dark shadow. My father, a well-known cardiologist and civil libertarian, had warned me not to come back at that time to India. The late Hari Sharma, a longtime friend of Daya and an acquaintance of my father, had asked Daya if I could be brought over to Canada. I had worked in Bio-Transport in the Chemical Engineering Department of my University and had been involved in developing polylactic acid membranes for Heparin transport. Daya got me into McGill University to work under him. He was researching the ulcerative and toxic effects of Butazolidin dosage on subjects suffering from malnutrition. While we did research, we were also dissecting the condition of the Indian state, organizing demonstrations in support of Indian people and bringing out papers, bulletins and books and sponsoring the talks of those who opposed the Emergency.

He had hundreds of fat rats on one hand and hundreds of thin rats on the other, getting the same dosage and getting tested for toxemia. A close parallel with the fat cats that run the world and the rest that suffer from them. Within an hour of his explaining the project to me, I realized that this man was not interested in furthering the cause of basic science as a personal academic career goal. Of course he had continuously published papers throughout his career, even much after his retirement, in the most highly respected medical journals. I had just arrived from the US and there all Indian PhD students and Post Docs pompously declared that they were doing “fundamental research” or “basic science.” Daya was clear. Reputedly with having completed the fastest PhD in McGill history (less than two years) he struck me as someone who wanted science and scientific research to be directly beneficial to today’s sufferers.

There will be many of us who will remember Daya as a Marxist thinker, as an organizer, as a prolific writer on the human condition, as a long-time supporter of fundamental social change in India. And rightly so. I will not get into that here. Daya went where others hesitated to go. In the interiors of Bhojpur, to Kashmir and Bhopal to meet with those who had a different dream for India. He was often excited about projects and put his mind to it very expeditiously. When some of these projects did not turn out as well as he had expected, he was frank about the disappointment. I knew that when Daya started a sentence by saying “Maybe…” he was going to come up with an idea that was totally antithetical to what he had proposed earlier or completely contrary to what was prevalent amongst social activists, as a popular notion. When an acute sense of disappointment and even a dystopic resentment crept in, Daya embodied the notions that George Bernard Shaw often displayed. “The moment we want to believe something, we suddenly see all the arguments for it, and become blind to the arguments against it. “ Daya lived that reality. He was his own detractor and thereby a tremendous source of inspiration for those who believed that for there to be advance there must be debate and struggle, continuous revisit of all paradigms, rather than compliance. So often, we heard friends saying “Oh! Daya, C’mon…..” Which simply meant that he would be saying the most provocative things possible to energize the debate. Of course there were some of us who were gullible enough. He was a discussant and an agitator. He was not interested in surface modalities, in mechanical radicalism and he recognized what was going through the minds of others and he would often say “I know what you are thinking….”

Of late I found out that Daya was always a much sought after bridge player. Key players in St. John’s wanted him on their team. Why? I researched a bit and found out that good bridge players remember sometimes fifty hands. They know how folks play the game. Daya knew this world in so many ways like the back of his hand. He remembered stuff from decades ago.

My deepest respect and revolutionary salute to him.