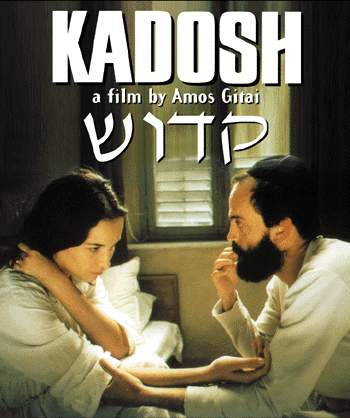

By making a film about Mea Shearim, the Orthodox Jewish quarter of Jerusalem, Israeli director Amos Gitai gives us a rare through-the-key-hole view of a sequestered, insular community. As a no-holds barred criticism of Jewish fundamentalism, Kadosh is successful. When it reaches for anything more complex than political hectoring, however, the film falls short.

As

an exile from the fundamentalist regime of the Islamic Republic of Iran, I

feel that there is no higher glory than a swift kick to fundamentalism's vital

organs -- for fundamentalisms are essentially the same, no matter which religion

they sprout from. But when it comes to the silver screen, I could be accused

of fundamentalism: I object to political agendas giving short shrift to character

development and good, cinematic story telling.

As

an exile from the fundamentalist regime of the Islamic Republic of Iran, I

feel that there is no higher glory than a swift kick to fundamentalism's vital

organs -- for fundamentalisms are essentially the same, no matter which religion

they sprout from. But when it comes to the silver screen, I could be accused

of fundamentalism: I object to political agendas giving short shrift to character

development and good, cinematic story telling.

Kadosh (meaning ‘sacred’) is the story of two sisters: the rebellious Malka (Barda) and the obeisant Rivka (Yael Abecassis). Their lives are hostage to oppressive religious practices, their fates managed by rabbis and Talmudic scholars in whom concerns over how to make tea on a Sabbath stir more passionate debate than the value of two individual lives. The individual doesn't matter; perpetuation of the community is everything.

The rabbi (Rav Shimon) tells his son Meir (Yoram Hattab) that only more and more children can help "vanquish the others" -- the others being the unorthodox, including the “‘secular government." In this end game, women play a crucial role, but merely as child-bearers. "The only task of a daughter of Israel is to bring children into the world,” exhorts the rabbi.

The demands of faith threaten the genuine, mutual love shared by Meir and his wife, the quietly iridescent Rivka. Their marriage of ten years is barren, so the Rabbi, invoking The Law, forces Meir to marry a fertile young woman who can produce children. Rivka meanwhile takes an unorthodox step and consults a doctor who determines that - Warning: big plot twist ahead - Meir is the sterile partner! In the Orthodox world, male sterility is a conceptual impossibility. Rivka, ever compliant, goes into exile with her secret while the rapidly shrinking Meir gets a new bride as dictated by his father the rabbi.

Unlike the hopelessly passive sister, Malka exercises her individual will, turning her life around by making a choice. She has long been in love with Yakov, a rebel stereotype complete with stubble and tough walk, who opted out of the orthodox community despite the pressures of his family and friends. Of course, he doesn't stray out as far, say, as the Intifida. He joins the Israeli army, which is orthodox enough for him to be able to say, "I'm still a good Jew," but also evil enough in Orthodox eyes for him to be ostracized. Consequently, Malka is forced to marry an uber-believer, a man who chants louder than the others, an ugly, boorish caricature of a zealot. At first Malka accepts this fate. But after a brutal deflowering (in a scene which wavers between sheer horror and comic effect without being successful at either), Malka runs out for a cheesy quickie with her true love, the soldier-turned-pop singer Yakov. It’s not clear why she returns home, but when she does she is beaten, so she decides to leave for good this time. On her way, she imparts some hard-earned wisdom to her sister: "There's another world out there." A platitude that would have resonated with more meaning in the mouth of a wrinkled extra terrestrial with a glowing red index finger.

There's enough wooden dialogue throughout the film to build a Yeshiva. When Rivka is condemned to exile, she concludes a wordy summation of her situation with: "I will rent a room." Cut to the next scene and, lo and behold, there she is entering a room carrying two suitcases. We should feel a sense of loneliness and loss in that moment, but the overly-exegetic dialogue robs us of the pleasure of empathy.

The point of the film is bluntly obvious: individual will is subordinated to the will of the community, and this leads to human suffering and tragedy. Trouble is, Gitai can not make us feel the tragedy or suffering. We merely recognize it as such because he tells us to. To wit, Rivka over dinner: "Meir, I can see you suffering because you don't have children." Gitai's long years as a documentarist, it would seem, did not serve him well in his first foray into fiction.

Which is a pity, because the film begins with great promise. A long, slow uninterrupted take introduces us to Meir as he conducts a mesmerizing morning ritual in preparation for his day at the Yeshiva. The scene’s underlying mystery and mysticism build up through Meir’s hypnotic chanting of lines such as "Blessed is our Eternal God who lifts up the fallen." Until we are hit with the ironic final chant: "Blessed is our father who has not created me a woman." Gitai’s camera then pans to Rivka, who in full earnestness says, "I have such respect for you." What makes this irony rich (and not easy) is that sets in opposition a fleeting, intimate moment against a strictly codified, ritualized way of life: there is no moralizing or expository statements. We feel the true depth of their love, and thereby feel the contradiction of their lives. It's a kind of moment that is never again repeated in the film.

Gitai's unflinching documentarist eye captures the rituals, the laws and the practices of this harsh, oppressive community. Though it is no fresh insight to suggest that religious fundamentalism is built upon an unquestioning adherence to patriarchal authority, the film's political point has been greatly appreciated by many, both in Israel and in North America, for having been made at all. The film may be a credit to Gitai's courage and moral backbone. But as a cinematic work of fiction, it has the depth and dimensions of a show of shadow puppets.

THE END